Behold the Great American Immigration Thermostat

Everything you wanted to know about our never-ending cycle of political backlash and overreach

Below is a guest post by my friend Alexander Kustov, an Assistant Professor of Political Science and Political Administration at UNC and recent author of In Our Interest: How Democracies Can Make Immigration Popular. Alexander has a long resume and several academic interests but I know him best for his polling work and analysis of public opinion on immigration policy. I asked him to summarize his work below now that public opinion is behaving exactly how he predicted before Trump took office a second time. If that doesn’t merit a guest post, then nothing does. Follow him on X too.

Election night 2024 delivered a shock to many immigration advocates: Donald Trump reclaimed the White House on an evidently popular anti-immigration platform. Conventional wisdom said this reflected a country turning decisively against immigration, as signified in the major reversal of public opinion on the issue over the last several years. This is also something that the Trump administration clearly embraced by cracking down on both illegal and legal immigration.

But an interesting thing happened next—polls began to show Americans becoming more pro-immigration. To the uninitiated, this whiplash seems baffling. To those versed in the idea of thermostatic politics, it’s practically routine. Understanding this concept is like having a prognostication superpower for making sense of public opinion and policy swings.

As I predicted back in November 2024, the election of Donald Trump will make American immigration attitudes great again, again. I also bluntly warned restrictionists that retaining their advantage on immigration among the public would require some serious policy work on streamlining skilled immigration pathways, and any significant hardline action beyond cracking down on illegal entries could backfire. This is exactly what happened—the administration overreached yet hasn’t delivered anything constructive, the long-held Republican advantage on immigration is now gone, and the average voter is swinging more pro-immigration yet again.

Thermostatic Politics 101

The counter-intuitive prediction—that Trump’s election and his anti-immigration actions would spur a reverse pro-immigration backlash—is rooted in decades of empirical research on the relationship between public opinion and political change across various contexts. As a descriptive matter, we now know that public opinion often moves against the prevailing party in power and the direction of its policies. When leaders push policy toward one extreme, public preferences tend to shift in the opposite direction—and politicians often respond. But what exactly is thermostatic politics, and why does it apply to some issues and times but not others?

The term, coined by political scientist Christopher Wlezien in his influential 1995 paper, likens public opinion to a household thermostat. If the political “temperature” moves too far in one direction, the public turns the dial the other way. In practice, this means that when government policy shifts left, public opinion shifts right, and vice versa.

Crucially, thermostatic responses don’t require voters to track policy details (which they often can’t). Instead, the public often reacts at a gut level to the perceived direction of change. Media coverage and partisan cues shape whether people feel things have gone “too far” or “not far enough.” When a new administration dramatically alters course, a portion of the public instinctively pulls back.

This creates a feedback loop: policymakers respond (or overcorrect), then opinion shifts again. The cycle produces regular swings in surveys—a pendulum that keeps policy from straying too far from public comfort. Indeed, one useful way to think about thermostatic responses is as a more common—but less extreme—form of public backlash, which is typically defined as voter pushback that ends up being counterproductive to a policy’s intended goals.

But the thermostatic model is not just about public pushback to political change. It’s also about how democratic governments respond to opinion shifts, which they actually do, albeit imperfectly. This two-way adjustment—where voters react to policy and policymakers, in turn, react to voters—is what makes thermostatic politics not just a theory of public opinion but a broader account of democratic responsiveness. Ideally, in a healthy democracy, elected officials are supposed to pick up on the thermodynamic signals from the public and recalibrate policy accordingly, creating a responsive feedback loop between governance and opinion.

Let’s Talk Nuance for a Moment: Absolute vs Relative Preferences

The basic principles of thermostatic politics are relatively well established and already offer a crucial corrective to competing academic and “folk theories” of democracy—whether the view that politicians simply mirror public preferences or that the public blindly follows elite cues. Still, there are certain more technical aspects of the theory and evidence that are often missed or misunderstood.

Most important, not all opinion measures are the same or can be equally thermostatic. A key distinction—often overlooked by pundits, policymakers, and even some public opinion scholars—is between relative and absolute preferences. Most polling data captures relative preferences: whether people want more or less of something compared to the status quo (which is also something that is easier to measure and that is what we see in most immigration polls). These are the views most susceptible to thermostatic change. When immigration increases or becomes more visible, people may say they want less of it—not because their underlying values have changed, but because they feel the current level overshoots their comfort zone. These responses function like error signals: turn it down, cool it off.

By contrast, absolute preferences reflect deeper, long-term beliefs about what policies should ideally look like. When it comes to immigration views of individual voters, these “ideal points” tend to change much more slowly—if at all. Someone might believe that immigration should be high but orderly, or limited to specific categories, but still rationally say “more” or “less” depending on who is in charge and what exactly they do. Crucially then, thermostatic swings in relative preferences do not imply changes in these absolute preferences. Just because people say “more immigration” now doesn’t mean they’ve abandoned their ideal of a well-managed, selective immigration system, for instance.

This distinction matters. When commentators cite a spike in “reduce immigration” responses as proof of a rising anti-immigrant tide, they often misread what is really a short-term correction. Voters may simply be reacting to perceived disorder or policy overreach. Their actual ideals—say, support for legal immigration by skilled workers or long-term residents—often remain stable.

The distinction also complicates cross-country comparisons: when Canadians and Japanese voters both say they want immigration “decreased,” those relative signals are not equivalent given the vastly different baseline levels. In both cases, voters may share a similar absolute preference for immigration that is integrated, economically beneficial, and under control—but their thermostat dials are responding to different policy temperatures. Understanding this helps us interpret polling shifts more accurately—and avoid mistaking normal feedback for deep ideological change.

The Immigration Thermostat in Action: From Obama to Trump to Biden to Trump Again

This wasn’t always the case (more on that below), but immigration may now be the best real-world example of thermostatic opinion in action. U.S. immigration policy has seesawed over the past decade depending on which party held the White House—and public sentiment has moved in the opposite direction at nearly every turn.

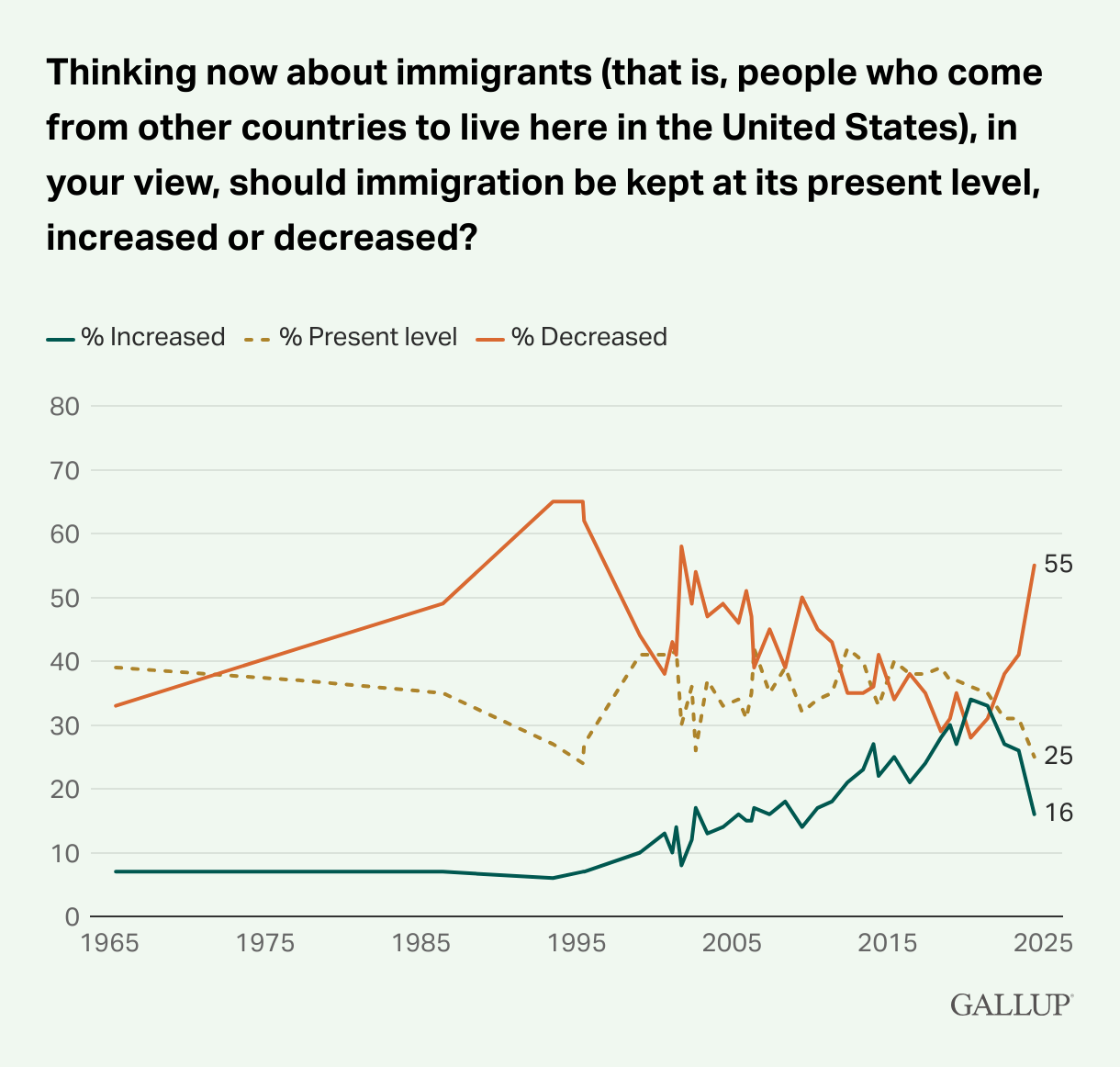

Although we don’t yet have the latest post-election update (which I expect will arrive in June and, as I pre-registered, should show more positive attitudes), this Gallup chart provides the most comprehensive overview of how Americans have changed their views on immigration over time:

As the chart shows, views on immigration have been trending upward for many years, especially since their post-9/11 low point during the Bush administration and into the first (and possibly the second) Obama term. During Trump’s first term (2017–2020), immigration enforcement hardened and restrictionist rhetoric intensified. And sure enough, public opinion shifted in a pro-immigration direction. By mid-2020, in the early aftermath of the pandemic, Gallup recorded—for the first time ever—more Americans saying immigration should be increased (34%) than decreased (28%). Support for immigration reached historic highs at the end of Trump’s presidency, despite (or likely because of) his administration’s restrictive approach.

Given these trends, when I began presenting research from my new book on making immigration popular, I was often asked why we should worry at all. After all, according to Gallup and many other surveys, support for immigration seemed to be rising on its own. Some immigration scholars even dismissed concerns about rising anti-immigration sentiment as a myth—or merely a product of misinformation.

But fast forward a few years, and we now know that public support for more immigration cannot be taken for granted. One way to interpret those earlier gains in immigration positivity is that they were exactly thermostatic and shallow—based on changes in relative preferences. As soon as Trump left office and President Biden began undoing many of his policies, the thermostat flipped. Biden’s more humanitarian—but often mixed and messy—approach coincided with surging migration at the southern border. The result: a sharp increase in public calls for reduced immigration. By early 2024, 55% of Americans wanted immigration decreased—the highest level since 2001.

Some analysts, including myself, have long cautioned that public enthusiasm for immigration has natural limits, and that it may have been exaggerated by recent opinion polls. Building durable support—especially for increasing admission levels—is difficult and can be undone by a single crisis at the border. And when you factor in routine polling uncertainty (due to random sampling and other errors, which Gallup curiously never visualizes), the apparent growth in pro-immigration sentiment looks even more fragile. In fact, it’s plausible that there has been no meaningful positive long-term change in U.S. absolute support for freer immigration since the 1990s.

Before President Trump’s inauguration, the two biggest questions in U.S. immigration policy were whether his administration would overreach and whether its general approach would be shaped more by its business-focused or nativist advisors. These questions have now been answered. With the administration deporting people without due process, revoking student visas, and detaining legal immigrants, it’s clear that the restrictionist hardliners have prevailed.

The predicted post-2024 pro-immigration swing appears to be following the script as well. With Trump’s return and promises of “tougher than ever” enforcement, most recent indicators from YouGov show the public’s mood softening again on immigration. While we still await the next Gallup release, the change in public views already appears in several polls and questions.

Why Immigration Is Thermostatic Now

A natural question is why we’ve seen such clear thermostatic back-and-forths on immigration in recent years, but not earlier. After all, the Gallup chart shows no major swings until at least the second Obama term.

We know that not every issue provokes thermostatic swings all the time. The most prototypically thermostatic issue, as originally identified by Wlezien, is government spending, in part because it’s relatively easy to observe on both the policy and public opinion side. Along with his co-author Stuart Soroka, he also identified two major factors that increase the likelihood of a thermostatic public response: high issue salience, which implies greater public attention, and a centralized institutional environment, which makes it easier for voters to attribute responsibility. Both of these conditions have recently converged in the case of immigration.

First, due in large part to the deliberate efforts of Trump’s 2016 campaign, immigration has increasingly shifted from a low-salience background concern to a top-tier issue in the public’s mind. Controversial rhetoric and polarizing policies—from building the wall to mass deportations and family separations—received sustained and intense media coverage, whether favorable or not. And when an issue becomes highly salient, the public is more likely to notice policy changes and outcomes—creating ideal conditions for thermostatic response.

Second, in the absence of meaningful legislative reform over the past several decades, U.S. immigration policy has seesawed through executive orders and enforcement priorities that each new president can reverse unilaterally. Trump’s approach—travel bans, asylum restrictions, ramped-up deportations—stood in stark contrast to Obama’s, and Biden then reversed many of Trump’s changes. This kind of policy whiplash is exactly what triggers thermostatic opinion shifts.

To my mind, though, the deeper reason why immigration has recently provoked consistent thermostatic responses is that, amid rising polarization on the issue, political elites in both parties have fundamentally misread what the public actually wants. The debate is often framed as a binary: open vs. closed, amnesty vs. deportation—each side catering to its base’s loudest voices. But in reality, most Americans hold a more moderate, nuanced view. As I show in my new book (see below), they support immigration that is controlled and clearly serves the national interest, and they oppose disorderly flows or any perception that the system lacks enforcement—even when that enforcement is being misused to harm immigrants, as it often is now.

Why Thermostatic Responses Are Not Dumb—They Are a Democratic Check

Thermostatic politics is often misunderstood, but it’s a vital feature of a healthy democracy. After I posted about the YouGov poll showing the post-election swing toward pro-immigration sentiment, the most common reaction—across the political spectrum—was that “the public is just dumb.” Interestingly, both the left and the right voiced this frustration, though for different reasons. On the right, some asked why voters would lash back against policies they had just voted for. On the left, others were dismayed that it apparently takes a Trump victory for Americans to rediscover their support for immigration.

Both were rightly puzzled by the timing. Why would public opinion begin shifting even before the new administration had enacted any policies? But that’s precisely the point: thermostatic responses aren’t always reactions to tangible changes—they’re often anticipatory, based on expected policy trajectories. Like investors pricing in future developments in the stock market, voters may adjust their views the moment an electoral outcome signals a likely policy direction.

This behavior isn’t irrational. In fact, the thermostatic model offers a more charitable—and arguably more accurate—interpretation: these shifts are a form of democratic accountability, not evidence of voter ignorance. When the public moves against whoever is in charge, it is performing a checks-and-balances function, signaling discomfort with perceived overreach. In the immigration context, that backlash can act as a brake, whether on excessively harsh enforcement or on overly permissive open-door approaches.

Many Americans who oscillate between “pro” and “anti” immigration stances are not contradicting themselves. They are responding to real-world conditions, institutional cues, and expectations. In effect, they’re saying: “We want immigration—but we want it handled competently and fairly for our benefit.” When they perceive disorder or grave injustice, they register their disapproval—not because their core values have shifted, but because they expect better governance.

Seen this way, thermostatic backlash is not a flaw but a democratic impulse. It helps nudge leaders back toward what the public sees as the national interest. Thermostatic responses are clearly preferable to blind loyalty to co-partisans and leaders, where voters cheer their side’s policies regardless of outcomes (which happens a lot, too!). For all its volatility, the immigration thermostat suggests that Americans are paying attention—and holding leaders accountable.

If Trump continues to overplay his hand with draconian measures, a swing back toward pro-immigration sentiment won’t be hypocrisy—it will be a rational demand for restraint, balance, or even just basic competence. Likewise, the backlash against Biden’s approach wasn’t a rejection of compassion, but a warning that compassion without control doesn’t inspire confidence.

Some critics dismiss thermostatic shifts as knee-jerk or uninformed, but sometimes good old thermostatic politics is the only thing that saves us from demonstrably bad policies. That is clearly evident in the public backlash to Trump’s new tariff regime, which pushes voters toward greater support for free trade—and it applies just as clearly to immigration today.

Breaking the Backlash Cycle: Making Immigration Popular by Making Better Policies

Thermostatic swings can serve as a democratic check—but how can we ensure lasting public satisfaction with immigration policy, rather than lurching from backlash to overreach to another backlash? The answer isn’t better messaging or louder rhetoric—it’s better policy. As I argue in In Our Interest: How Democracies Can Make Immigration Popular, the way forward is to tangibly align immigration policy with the public’s values and preferences for policies that are demonstrably beneficial or those that are explicitly and straightforwardly seen as serving the national interest.

What would those policies look like? In short, they’d pair tough security and tangible national benefits that skeptics demand with the opportunity and compassion that supporters value. Canada is a living example of a country where this approach has largely worked, at least until recently. In the U.S., workable reforms could include expanded legal pathways for workers, including those that explicitly prioritize those with skills or who fill specific economic needs.

My research shows that freer immigration gains lasting approval when democratic governments deliver policies tied to tangible national gains, like streamlined or increased high-skilled immigration. By contrast, preaching alone—“immigrants are good for you, don’t be xenophobic”—falls flat when paired with visible dysfunction. Competence builds trust; chaos, whether it’s immigration-friendly or not, invites dissatisfaction. The empirical evidence is clear: when immigration is more demonstrably beneficial, the public responds with support. At the same time, there is not a single country in the world that has managed to make immigration relatively popular without being selective in its admissions.

Breaking out of the great American immigration thermostat will take political courage. It means resisting partisan extremes and thinking beyond the next electoral cycle. But the reward could be a new equilibrium—one where immigration policy doesn’t provoke constant public recoil, because it earns broad legitimacy.

Fortunately, popular support for immigration doesn’t hinge on restricting it to elite professionals or adopting technocratic point systems. What matters most is whether the public sees immigration working in the national interest. Programs that address concrete needs—bringing in seasonal workers to stabilize food supply chains, international students who contribute to local economies and research, or newcomers who help reverse demographic decline in certain areas—can all gain legitimacy when their purpose is transparent and their outcomes are tangible.

The recent pro-immigration bump following Trump’s 2024 win is both a reminder and a challenge. It reminds us that American attitudes on immigration are more flexible and pragmatic than pundits assume. And it challenges future policymakers—those who may govern more responsibly in 2026 or 2028—to use this opening wisely. Relative warmth toward immigration is a chance to enact durable, evidence-based reforms. Rather than swinging to the opposite extreme or proclaiming “the people are with us” (until they’re not), leaders should focus on policies that both the experts and the public can recognize as functional and in the national interest.

Sustainable support won’t come from shaming skeptics or preaching louder. It will come from governments showing that immigration can be managed well, for the good of all. The thermostat will keep ticking—but with better calibration, we can finally set the temperature to “just right.”

Nice piece. I appreciate the hat tip to Canada, and I think comparing the U.S. and Canada on immigration can be illuminating. I hope we in the states can begin to emulate our neighbors on immigration. Your piece helps illustrate some of the reasons we struggle to do so.