Ethnic Attrition

Why Measuring Immigrant Assimilation Is Hard

In 2016, the National Academy of Sciences published a comprehensive report on the pace of immigrant assimilation in the United States. Its short conclusion: Current levels and assimilation rates are on par with previous waves of immigrants. I want to highlight one section of their report that explains why assimilation is rapid and is only occasionally mentioned by some and totally ignored by others: ethnic attrition.

Ethnic attrition occurs when the descendants of immigrants from a particular country, like Mexico, cease to identify as Mexicans, Hispanic, or Latino in surveys. It almost entirely occurs through intermarriage with spouses of different ethnic groups. Intermarriage as a source of ethnic attrition wouldn’t matter, except that ethnic attrition is selective, not random, and is severe (see Table 1). Subsequent generations descended from Spanish-speaking immigrants who identify as Hispanic, Mexican, or Latino systematically differ from those who are descended from the same Spanish-speaking immigrants but who drop the self‐identification.

Therefore, the problem is that you can’t use polls of self‐identified Mexicans, Hispanics, or Latinos born here to form an accurate picture of multi‐generational assimilation. Any poll of those groups will only catch those who self-identify as such, not those born here to Mexican, Hispanic, or Latino parent(s) who do not.

Studies that rely on the subjective Mexican self-identification of immigrants’ descendants find low rates of economic and educational assimilation that stall between the second and third generations. However, significant educational and economic progress is found after correcting for ethnic attrition and measuring all immigrants’ descendants. Below are the major papers in the ethnic attrition literature.

Duncan and Trejo’s 2007 seminal paper showed that Hispanic self‐identification fades by generation and that correcting for ethnic attrition reveals far more socioeconomic progress than other methods of measuring assimilation. Looking at the microdata from the 1970 US Census for everyone who had at least one ancestor from a Spanish-speaking country shows significant attrition (Table 1). Virtually all (99 percent) of immigrants from Spanish-speaking countries self-identified as Hispanic, 83 percent of the second generation, 73 percent of the third, 44 percent of the fourth, and 6 percent of the fifth and higher generations.

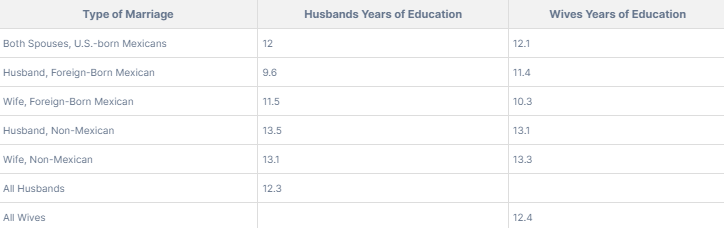

Intermarriage plays a central role in explaining the rapid loss of Hispanic self-identification. In the 1970 data, 97 percent of Americans with Hispanic ancestry on both sides of the family self-identified as Hispanic, while only 21.4 of those with Hispanic ancestry on one side of the family did so. Their analysis of 62,734 marriages in the 2000 Census found a high rate of intermarriage (Table 2).

Duncan and Trejo found a positive educational (Table 3) and economic selectivity for Mexican-Americans whose spouses were from other ethnic groups. In other words, Mexican Americans who are more educated are also more likely to intermarry with other ethnic and racial groups. 60 to 52 percent of the children from mixed marriages do not self-identify as Mexican. For third-generation Mexicans who marry a non-Mexican, between 66 and 53 percent of their children do not self-identify as Mexican.

The Mexican-American spouses in mixed marriages have at least a year more of education than Mexicans in non-mixed marriages, the children of those marriages gain even more education, and a majority of their children don’t self-identify as Mexican. Adjusting for ethnic attrition significantly shifts how we view the educational and economic assimilation of the descendants of all Mexican immigrants.

Richard Alba and Tariqul Islam (2009) argue that self-identification research fails to accurately measure assimilation due to intermarriage, echoing Duncan and Trejo. Alba and Islam find that Americans with mixed Mexican ancestry are less likely to identify themselves as “Mexican Americans” in the Census. Another problem is that the Hispanic-origin question on the 1980, 1990, and 2000 censuses changed and encouraged Americans of Mexican descent to identify themselves pan-ethically as “Hispanics or Latinos” instead of as “Mexican Americans.”

In a later paper, Alba and Islam (2011) find that those who self-identify as Mexican-Americans tend to do poorly in socioeconomic advancement, especially in education, compared to other immigrant groups. However, the descendants of Mexicans who are of mixed ancestry are the most likely to not self-identify as Mexican and tend to be more educated than other Mexican Americans.

Duncan and Trejo built on their earlier work with 2009 and 2011 papers that found Mexican Americans who do not self-identify differ systematically from those who do. Mexicans who intermarry have higher levels of human capital, and their children do not self-identify as Mexican in Census data.

For instance, second-generation Americans who have only one parent and were born in Mexico are more educated than those with both parents who were born in Mexico. The latter group is also 10 percent less likely to be deficient in English, and their children are 9.5 percent less likely to self-identify as Mexicans. This conclusion was partly preceded by a 2005 paper by Delia Furtado that found human capital and intermarriage increase immigrant adoption of native culture, boost assimilate rates for their children, achieve higher socioeconomic attainment and possess higher human capital.

Duncan and Trejo’s 2009 and 2011 papers used a new measure to identify Mexican-Americans who do not self-identify as such for the first and second generations. Their new method discards the self-identification data and instead relies on identifying all respondents born in Mexico and those who have at least one parent born in Mexico. Their new method is better at identifying first and second-generation Mexican-Americans, but it cannot identify third, fourth, or subsequent generations due to a lack of data from previous Censuses.

In twin papers published in 2011 and 2012, Duncan and Trejo apply their new method to compare Mexican ethnic attrition to ethnic attrition for other Hispanic (Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Salvadorans, and Dominicans) and Asian immigrant groups (Chinese, Indians, Japanese, Koreans and Filipinos). They find that Mexicans and their American-born descendants do show the lowest rates of ethnic attrition in the first and second generations. However, there is a “catch-up effect” for the children of mixed-ancestry marriages where one spouse is Mexican.

Duncan and Trejo in 2015 and Frank Bean et al. in 2011 argue that a large number of Mexican illegal immigrants produced a lower rate of ethnic attrition. Mexican unlawful immigrants have limited job opportunities, take lower-skill jobs, and have less education and fewer skills, meaning that they are less likely to intermarry or pass opportunities on to their children. This explains why it takes more time for Mexican Americans to achieve the same level of education and wages as other immigrant groups – an effect called “delayed incorporation.” Legalizing them would speed up assimilation.

Quick survey results from self‐identified Americans of Mexican, Hispanic, or Latino origin are not a reliable gauge of assimilation because they miss many second, third, and later-generation descendants of immigrants who don’t self-identify as such. Properly adjusting for ethnic attrition reveals substantial assimilation of Mexican, Hispanic, and Latino immigrants and their descendants.

Adapted from earlier blog post here.

Alex, I love your work. I live in San Francisco and hale from Kentucky, with family still there; so I see the cultural divide up close and personal. And no issue is larger than immigration. Personally I doubt the narrative that our society is ending because of illegal immigration, yet I also doubt the narrative that it causes no harm, and all peoples have equal chance of advancing the US economically.

It would be nice to know the truth in an unbiased way.... and if i worked at a think tank on an issue like this, here is what I might consider:

Select a given year like 1910, and a give age range like 20-30. then use use census data and randomly select many thousands of people in that year of that age. now do the same for both legal and illegal immigrants of that time. (well I dont' know how many illegals are caught an documented at that time... so it might have to be legal immigrants. Then use one of these geneiology services

to try to track these orginating folks into the present day. Many will fail to track forward, and some will incorrectly map as you only have location and name to work with. And only the wealthy screw around putting their data into these databases. Still these biases should operate similarily over both populations.

Now one can really compare how things turn out 100 years later. I bet the answer lies somewhere in the middle. But wherever it lands, it would be a powerful way to see what the REAL consequenes are. Even congress today is making real choices about the future shape of our nation w/o really understanding what they are doing.... what the real consequenses are.

For me, I am in the middle. I dont' know what to expect. On the one hand culture and economic context does transfer strongly from generation to generation. On the other hand 100 years is a LONG time, and as you noted in the article here, after that time a person might not even really think of themselves in that light. For example I am ethnically more almost 70% German. but it has no bearing on me or my identity.

Anyway.... if such work were ever done, it would be an advancement for the nation. (and perhaps you know a professor somewhere who is not so ensconced in their echo chamber as to be willing to really look at where the data lead.)

love your work.

--dan