I Was Right Again and Other Recent Immigration News

My recent media appearances and an LSE lecture on nationalism

Earlier this month, David J. Bier and I wrote how the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) paused the CHNV parole program, which allowed over 520,000 migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela to enter and work legally in the United States. CHNV was the largest immigration liberalization since 1968 and helped reduce illegal entries by hundreds of thousands since its launch. DHS paused it because of silly fraud concerns raised by data inconsistencies that afflict every database ever created:

Until now, nearly all immigration applications were filed on paper. For the first time in its history, DHS required all CHNV parole applications to be filed online, resulting in a monstrous data file of 2.6 million records. The agency's Fraud and National Security Directorate (FDNS) apparently took its first stab at assessing "potential fraud indicators" within it.

FDNS found blank entry fields, phone numbers that don't work, zip codes that don't exist, strange street addresses, Social Security numbers associated with dead people, repetitive text and repeat filers, and other similar anomalies. FDNS concluded that these issues indicate fraud.

But those oddities and errors are not evidence of fraud—they are part and parcel of large administrative datasets, especially those compiled by the government. Fraud involves intentional deception, deliberate misrepresentation, or omission by applicants to obtain benefits they do not qualify for. These issues are more likely due to changing circumstances between the time when the forms were filed and the FDNS analyzed them, copying-and-pasting between different types of electronic documents, and simple human error.

Finding mistakes like this in big data is absolutely normal. For starters, statistically, some sponsors have certainly died since filing their sponsorship applications. The bigger issue is that when 2.6 million people fill out a form—sometimes on behalf of a relative or client—errors such as transposing numbers and letters, writing their mailing address when they should write their physical address, or mixing up mailing and physical addresses are inevitable.

Bier and I both thought the Biden administration would restart CHNV as soon as they could find some butts to kick at DHS. And we were right. Just a few days ago, the Biden administration announced that it was restarting the program. If you want to know what’s happening with immigration, read me and David Bier.

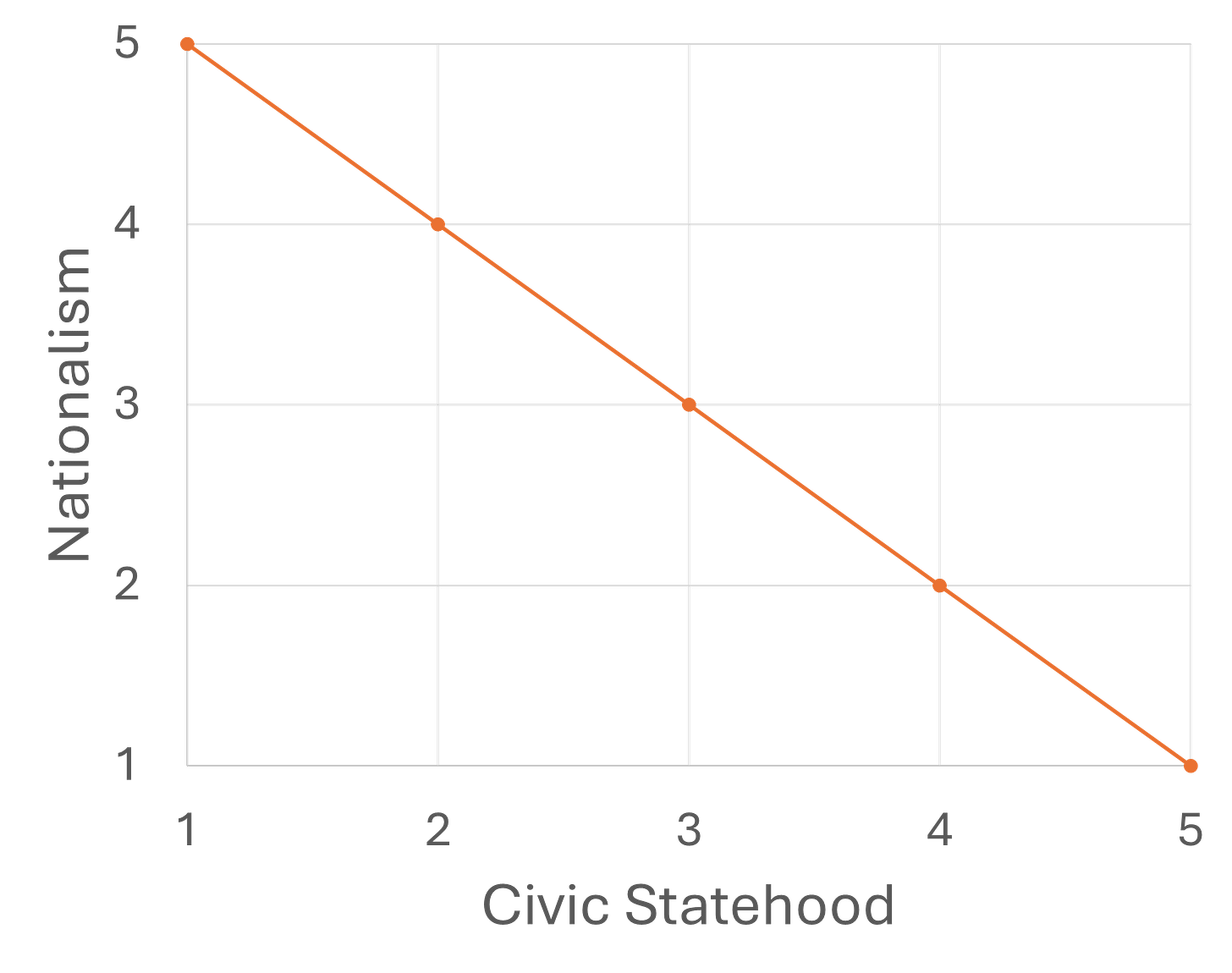

The inimitable Bryan Cheang at LSE and King’s College invited me to give a lecture about nationalism. I explain my usual criticisms, but also some more moderate statements about it. Every country has an identity on the blood and dirt to civic spectrum, and no country is all one or the other. The United States is much closer to the civic end of the spectrum, but there are still some markers of identity, like fluency in the English language, that aren’t grounded in civic values or support for the spirit of the Constitution. American identity has expanded widely over time to include non-Protestants, nonwhites, and others so far that we’re much closer to the civic side.

I’m not sure how much further we can go, but I don’t expect English to leave that market of American identity any time soon. Country identities change over time through internal evolution and from exogenously, from immigration or other influence by foreigners. American nationalist thinkers today have a very different message than those from a century ago.

Watch my lecture here.

Crime is a major point of debate regarding immigration. Cato scholars have produced the best work estimating illegal immigrant crime rates (here are our recent reports on it). Thus, there is much market demand for our commentary. Below is a recent interview I did with NPR on the topic, focused on Texas.