Immigrant Children and School Choice

Immigrant and Native Enrollment in Private and Public Education

Several states have reformed their educational systems in the face of increased dissatisfaction with public education during and after the COVID-19 pandemic school closures, a desire for parents and children to have more choice, and other sources of dissatisfaction. Many of those reforms have increased school choice by creating or expanding education savings accounts, tax credit scholarships, or other reforms. Some commentators and politicians claim that immigrant access to school choice programs are reasons to oppose them—especially when the students or their parents are illegal immigrants.1

Based on data from the American Community Survey (ACS), we find that 9 percent of immigrants enrolled in K–12 education were in private schools during the 2015–2022 period, compared to 16.3 percent of native‐born American students. Private school enrollment rises to 11.2 percent in the second generation and to 17.8 percent in the third‐plus generation. This result holds for all household income brackets, with some variation. We also compare immigrant and native‐born American enrollment in private and public schools based on the number of children in the household, parental education, race, national origin, and state of residency.

Background

Immigrants’ consumption of government services is a contentious point of debate within immigration policy. The Cato Institute and others have analyzed immigrants’ consumption of welfare and entitlement benefits as well as their net‐fiscal impact, but there is a scarcity of research on immigrants’ enrollment in public and private education compared to native‐born Americans.2

The latest attempt to estimate native and immigrant enrollment in public and private schools is a 2001 paper by Julian R. Betts and Robert W. Fairlie that relied on 1990 census data.3 They found that native‐born American children had higher rates of private schooling than immigrants. About 11.8 percent of native‐born American children were enrolled in private K–12 school compared to 7.5 percent of immigrants in 1990. The authors found a similar gap for secondary school, where 10.03 percent of native‐born American children were enrolled in private schools compared to 6.17 percent of immigrant children. Betts and Fairlie found that these gaps are explained by differences in race, income, and parental education.

More recent research focuses on two other topics related to immigration and education. The first is the increasing enrollment of immigrants in American schools. A 2023 report by the Center for Immigration Studies mapped growth in the number of immigrant families that enrolled their children in public schools.4 The US Census Bureau reports that students who are immigrants themselves, rather than the US‐born children of immigrants, make up around 6.6 percent of all students in the country—lower than the immigrant share of the population in 2022, which was at 13.9 percent.5 The same Census report states that around 12.8 percent of all students enrolled in K–12 school in the United States are enrolled in private school and that 4.4 percent of students enrolled in K–12 are immigrants, but it does not present data on the nativity of students in public or private education.

The second major topic explored by researchers in this area is so‐called “native flight,” whereby native‐born Americans take their children out of public schools and enroll them in private schools when immigrants’ share of the population in local public schools increases. Multiple non‐causal studies have provided evidence for the existence of native flight in the United States and other countries, so it is possible that the presence of more immigrants in public schools has widened the gap in private school enrollment between immigrants and natives.6

This brief provides updated estimates of public and private school enrollment among immigrants and natives. We find that 9 percent of immigrants enrolled in K–12 education were in private school during the 2015–2022 period, compared to 16.3 percent of native‐born Americans. Private school enrollment rises in the second generation (the US‐born children of the immigrants) to 11.2 percent, and again in the third‐plus generation (the US‐born grandchildren of immigrants and those who have even deeper roots in the United States) to 17.8 percent. This general result holds for all household income brackets with some variation. About 38.5 percent of first‐generation immigrant children in households making more than $750,000 per year are enrolled in private school, compared to 42.9 percent of native‐born children in households in the same income bracket. We also show results for private and public school enrollment segmented by the number of children in the household, parental education, race, national origin, and state of residency.

Data Sources and Methodology

The primary data source for this brief is the ACS, an annual survey that reports economic, demographic, and housing characteristics of the US population, from which we obtain individual‐level data on nativity, birthplace, income, age, school type, education level, family characteristics, and geography. This brief uses the ACS one‐year estimates from 2015 to 2022.7 The ACS provides various samples for different purposes, such as the five‐year estimates, which are preferred when analyzing small populations and when the most recent data are not needed. The one‐year estimates should be used when having the most current data are preferred and when the populations being analyzed are large.8 For our purposes, the one‐year estimates are ideal. The appendix contains a list of all variables used in this brief.

To adjust household incomes for inflation, we use the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.9 We prefer the PCE to other inflation measures such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI) because the PCE incorporates substitution effects between goods in its inflation basket and has a more appropriate scope than that of the CPI, as it considers both urban and rural populations and accounts for all expenditures made on behalf of consumers rather than only out‐of‐pocket expenses.10 All incomes are reported in 2022 dollars.

While the ACS used to report the birthplaces of the respondents’ parents, this question has been omitted from the survey for decades.11 However, it is still possible to fill in this information for respondents so long as the respondent’s parents are also in the data. Respondents whose parents are also in the ACS data are disproportionately young, but so are respondents enrolled in school. Rates of private school enrollment among the full ACS sample population are thus nearly identical to those among the respondents we can analyze. Unless otherwise stated, results presented are only for respondents enrolled in either public or private school, including homeschool. For the years we include, the ACS defines “school” as “any nursery school, kindergarten, elementary school, and any schooling leading toward a high school diploma or college degree.”12 This includes homeschooling, but the data do not allow us to separate homeschooling from other forms of nonpublic education. We confine our analysis to K–12 education or, in other words, high school and below.

We define three generations of immigrants. First‐generation immigrants are respondents born outside the United States and its territories, excluding those born abroad to American parents. The second generation are respondents born in the United States to foreign‐born parents. The third‐plus generation are respondents born in the United States to native‐born parents. Respondents with one foreign‐born parent and one native‐born parent are randomly allocated between the second and third‐plus generations with equal probability, following the methods of the National Academy of Science in analyzing the net fiscal impact of immigration.13 If a respondent was born in the United States but we are unable to fill in their parents’ birthplaces, they are dropped from the sample because their immigrant generation cannot be determined. The final sample of enrolled respondents consists of 5 percent first generation and 95 percent native‐born Americans, with 18.2 percent in the second generation and 76.8 percent in the third‐plus generation.

Past Cato policy briefs have identified likely illegal immigrants in the ACS data using a residual statistical method, whereby individuals likely to be legal immigrants are identified and the rest of the foreign‐born population is assumed to be illegal immigrants.14 While the presence of illegal immigrant children in private and public schools is certainly relevant, such methods would not yield robust or reliable results when applied to school enrollees because much of the residual method relies on employment history, military service, and other characteristics that only adults are likely to have. We are therefore not able to separate out legal and illegal immigrants with any reliability.

The ACS considers “Hispanic” to be an ethnicity, not a race, but reports whether respondents are of Hispanic origin. If respondents report themselves as being Hispanic, we consider them “Hispanic of any race” regardless of how they answered the “race” question. Country of origin is equal to the respondent’s birthplace if they are first‐generation immigrants. Parental education levels are standardized into five distinct levels: less than a high school education, high school or equivalent education, some college but no degree, bachelor’s or equivalent degree, and post‐graduate education. Aggregated results are weighted using the provided person‐level sample weights from the ACS. Unless otherwise stated, the results report the percentage of enrolled respondents who attend private rather than public school for pooled 2015–2022 data.

Results

Only 9 percent of immigrant children are enrolled in private school rather than public school, compared to 11.2 percent for the second generation, 17.8 percent for the third‐plus generation, and 16.3 percent for all natives (Figure 1). The gap in private and public school enrollment between immigrant students and native‐born students has widened overall, and for each generation, since at least 2015 (Figure 2). All groups were more likely to be enrolled in private school during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. However, the enrollment of immigrant children in private school fell back to its pre‐COVID‐19 levels in 2021, while it stayed elevated for native‐born American children.

Rates of private school enrollment differ significantly by income bracket. Unsurprisingly, high total income households have significantly higher private school enrollment. Immigrant households with annual incomes of at least $750,000 were 6.5 times as likely to enroll their children in private school compared to immigrant households with incomes of less than $100,000 per year. All native‐born American households with incomes of at least $750,000 per year were 3.5 times as likely to enroll their children in private school compared to native‐born household with incomes of $100,000 per year or less.

Additionally, enrollment rate gaps between immigrant generations vary significantly by income bracket. At the lowest income bracket, immigrant and second‐generation children are enrolled in private school at 5.7 percent and 5.6 percent, respectively. Private school enrollment rates for the third‐plus generation and all native‐born children are 13.3 percent and 10.5 percent, respectively, in the lowest household income bracket. The difference in private school enrollment rates for all native‐born children and the third‐plus generation, compared to all immigrant children and the second‐generation, narrows considerably as income rises, but the gap remains (Figure 3).

Rates of private school enrollment are positively correlated with the number of children in the household (Figure 4). The data in Figure 4 are likely capturing the religiosity of the household through the proxy measurements of the number of children and private school enrollment. Religious families are more likely to enroll their children in private schools and to have higher fertility.15 Immigrant children are still the least likely to be enrolled in private schools, controlling for the number of children in the household. The difference is so stark that households with nine or more immigrant children have a lower enrollment rate in private schools than native‐born households with one child. Households with third‐plus generation children have the highest private school enrollment rates of any generation, controlling for the number of children in the household.

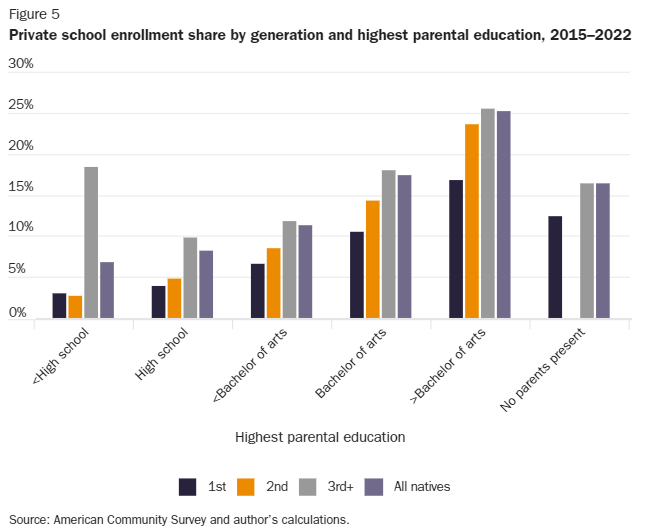

Parents with lower levels of education are generally less likely to send their children to private school in each generation, but this is especially true for immigrant children (Figure 5). For families in which the most educated parent in the household has not even completed high school, 18.4 percent of third‐plus generation children are enrolled in private school—more than six times the rate of first‐generation immigrant children, at 3 percent, and almost seven times the rate of second‐generation immigrants, at 2.7 percent. This general pattern holds when categorizing based solely on the mother’s education (Figure 6) or solely on the father’s education (Figure 7).

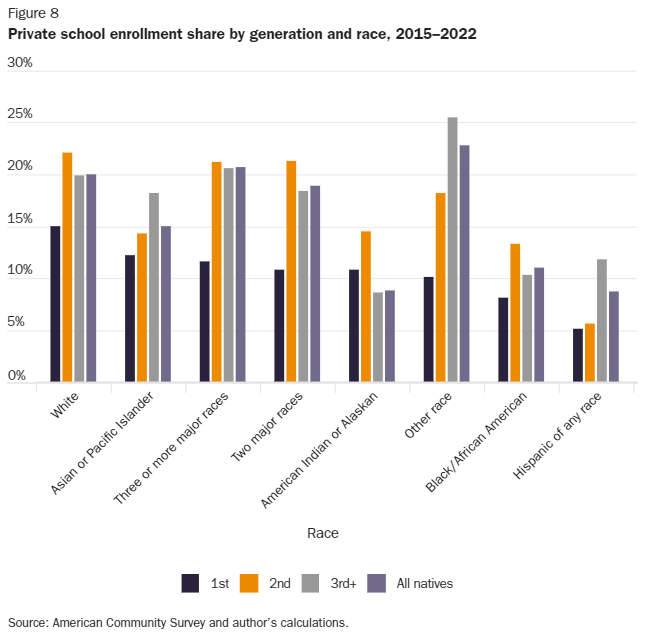

Rates of private school enrollment differ significantly by race (Figure 8). Whites, Asians, and respondents who are of mixed race tend to have the highest rates of enrollment in private school overall and across generations. Blacks and Hispanics tend to have the lowest rates. With some exceptions, students are more likely to be enrolled in private schools when they are part of longer‐settled generations.

Immigrants from Central America, Africa, and the Middle East tend to opt for private school at lower rates than those from Europe and Asia, with some notable exceptions. Table 1 includes the enrollment rates for the top 20 countries of origin for immigrants with at least 10,000 enrollees. Belgian‐born students have the highest proportion of enrollment in private school at 33.1 percent. Eleven of the top 20 countries are European. Students from the Ivory Coast have the lowest enrollment in private school at 0.9 percent (Table 2). Six of the bottom 20 countries of origin are in Central America and the Caribbean and seven are in Africa.

There is also significant variation in enrollment in private schools across American states. Washington, DC, has the highest enrollment rate for first‐generation immigrants and for the second generation, at almost 21 percent and 23 percent, respectively. Hawaii has the highest rate of private school enrollment for the third‐plus generation, at 28 percent, and is tied for the highest among all natives with the District of Columbia and Louisiana, at 26 percent. North Dakota has the lowest rates for first‐generation immigrants, at 2.6 percent, and Wyoming has the lowest for the second generation, at 5.2 percent. Utah has the lowest rate of private school enrollment for the third‐plus generation and for all natives, at 10.2 percent and 10 percent, respectively. West Virginia and Wyoming are the only states in which immigrants are enrolled in private school at higher rates than natives.

Discussion

Our headline finding is that 9 percent of immigrant children were enrolled in private school during the 2015–2022 period, compared to 16.3 percent of native‐born Americans. Enrollment in private school is higher for the second generation, at 11.2 percent, and higher yet for the third‐plus generation, at 17.8 percent. Even at high income levels, immigrants are less likely to enroll their children in private schools. Controlling for race, ethnicity, family size, and education, immigrants are less likely to be enrolled in private school than native‐born Americans. There is substantial regional variation, but in only two states (West Virginia and Wyoming) are immigrants more likely than natives to be enrolled in private rather than public school.

The gaps between immigrant and native rates of private school enrollment are smallest at the extremes of the income distribution. At the lowest income bracket, this gap is 4.8 percent; at the highest income bracket, it is 4.4 percent, whereas it is over 6 percent in the middle income brackets. This could indicate that when income is not a determining factor, cultural factors such as immigrant status, country of origin, or the relative valuation of educational quality may play more of a role in family decisions regarding private school enrollment. The positive relationship between family size and rates of private schooling, especially among natives, also suggests that cultural factors—namely religiosity—may occasionally override price as the determining factor in school choice.

Lastly, the observable increase in private schooling during the COVID-19 era suggests that many families were pushed toward private schooling by prolonged public school closures, masking requirements, or other factors. However, only natives opted to stay enrolled in private schools after the end of the pandemic. The first generation of immigrants returned to its previous level of private schooling shortly after the pandemic, whereas native‐born groups have since maintained a new elevated level of private schooling. This may reflect more flexibility in school choice among natives conferred by higher median incomes or because they reside in states that offer more school choice.16

Conclusion

We find that only 9 percent of immigrant children were enrolled in private K–12 school during the 2015–2022 period, compared to 16.3 percent of native‐born American children. This gap varies by immigrants’ country of origin, but it generally holds even among immigrant households with higher incomes and education levels. There are many potential partial explanations for this gap, including differences in household income, values, relative expectations of the quality of education, immigrants being less likely to reside in states with school choice, native flight, or other factors not considered.

Read the Cato paper here.