Public opinion drives government policy in democratic countries. Of course, public opinion isn't the sole driver as interest groups, the individual quirks of politicians and bureaucrats, and institutional incentives all matter by diverting popular public policies to serve their interests. For instance, agricultural subsidies exist because American voters want them, but which farmers and crops get subsidized is affected by interest groups like the sugar lobby. Thus, one must understand public opinion and interest groups to understand which policies are in effect and why they are run so oddly. But what drives public opinion can sometimes be mysterious and nonobvious. I’m going to focus on what drives public opinion on immigration.

I have less faith in issue polling than most, but there appears to be a strong relationship between how chaotic the border is and what Americans think of immigration broadly. Gallup asks the question: “Thinking now about immigrants -- that is, people who come from other countries to live here in the United States, in your view, should immigration be kept at its present level, increased or decreased?”

Americans have generally become more pro-immigration over time but notice the uptick in the desire to decrease immigration from 28 percent in 2020 to 38 percent in 2022. What happened? The number of Border Patrol apprehensions of illegal border crossers rose dramatically.

Starting from a low point in April 2020, apprehensions rose rapidly along the border and really took off in January and February of 2021 when President Biden took office and the job market took off (the two are not related). In addition, the delayed effect of the Trump administration's issuance of Title 42 in March 2020 as an anti-COVID policy resulted in the immediate return of apprehended illegal border crossers. As I predicted, this would result in a massive increase in illegal border crossers:

Title 42 expulsions also lower the costs for illegal border crossers. By removing them very rapidly and not enforcing consequences, apprehended and expelled illegal border crossers face lower costs in their attempts to cross the border. Thus, we should expect more of them to try and the recidivism rate to rise beginning in March 2020, ceteris paribus. Of course, not all else remains equal as the U.S. recession has somewhat dimmed the jobs magnet that attracts most illegal immigrants in the first place, although the relative difference is likely smaller given the recession in Mexico. When recidivism data become available for 2020, I suspect we’ll see an increase in recidivism rates compared to earlier years as the consequences have been so reduced.

Repeat crossers jumped to 26 percent of all apprehensions in 2020 from 7 percent in 2019, growing further to 27 percent in 2021. David Bier highlighted this anecdote: “They are sending back people very quickly, in hours,” said one Mexican seeking to cross. “The rumor is that chances of crossing undetected are higher, as you can try and try again without much consequences.” That perfectly aligns with the incentives created by Title 42 that I highlighted. Combined with perceptions that the Biden administration would create more lenient border policies, the incentives of Title 42 increased the number of apprehensions along the border.

Additionally, the vast increase in labor demand in the United States is obviously attracting many illegal immigrants who come here to work. The number of illegal border crossers apprehended is the crucial metric for my point that border chaos drives public opinion on immigration. Illegal border crossings by the number of individuals likely peaked decades ago, but the perceptions of chaos come from the apprehensions and not the actual numbers of people coming. Keep that distinction between apprehensions and individuals in mind.

The public perception of chaos along the border, driven by the number of apprehensions, has shifted public opinion on immigration toward favoring decreased immigration. People don't like chaos, and they are reflexively opposed to activities that appear chaotic. This is true for illegal activities, but that perception spills over and reduces support for legal immigration too. The public doesn't care about the distinction between the number of illegal border crossers and apprehensions, they react to the chaotic images and see the number of apprehensions. Thus, they shift toward opposing immigration and favor enforcement to decrease the chaos. Since democracy translates voters’ opinions into policy, voter perceptions, true or not, are what matter. The perception of the border is one of out-of-control chaos. You're very unusual if pictures of chaos don't bother you.

Donald Trump ran with the slogan “build the wall” because chaos disturbs people. He didn’t run on the slogan, “reduce legal immigration,” even though his platform called for just that. In practice, the Trump administration reduced legal immigration and didn’t make a dent in illegal immigration, but illegal immigration and the resulting chaos were the political justifications for his immigration actions.

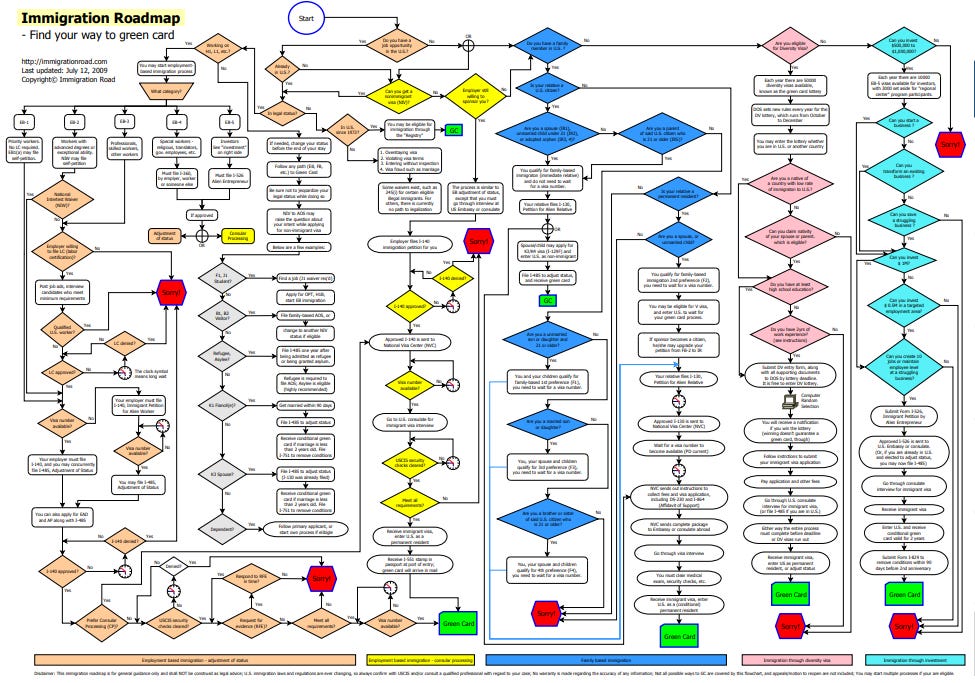

If the illegal border crossers had instead entered in an orderly manner through a port of entry under a legal immigration system that could accommodate them, then only a handful of nativists would care. But the legal immigration system is so enormously complex and restrictive that very few can enter legally, thus leaving illegal immigration as the only option. Check out this highly simplified flowchart of only one portion of the legal immigration system.

Public support for increasing immigration rises as the number of border apprehensions falls. Likewise, more people want decreased immigration as apprehensions rise. Growing public support for boosting legal immigration thus requires the perception of government control over the border and minimal chaos. Public perception of the chaos is crucial, but those perceptions will only change if reality also changes. Getting into semantic debates, pointing out that many border crossers are asylum seekers legally entitled to apply, or quibbling about the numbers won't change public perception. Those points are often interesting, but they won't change the fundamental underlying driver of public opinion on immigration.

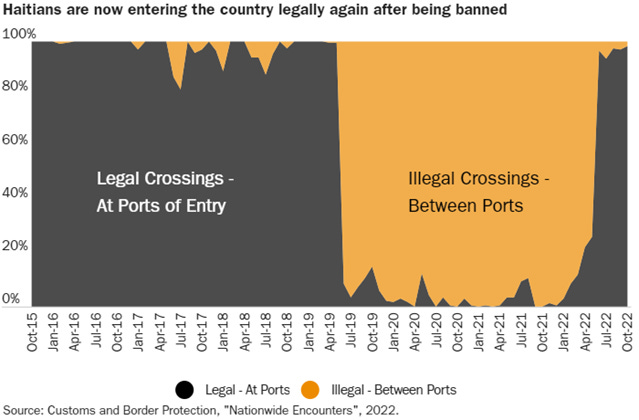

The catch-22 of immigration reform is that control of the border is politically necessary for expanding legal immigration, but the government can’t get control without expanding legal immigration. Channeling would-be illegal immigrants into the legal immigration system reduces chaos and increases government control over the border. President Biden’s latest action on immigration sounds like a big step toward fixing this. Notice how the administration’s fact sheet leads with enforcement while the portion allowing in more lawful immigrants comes after. The fact sheet begins with enforcement because the public thinks more enforcement will reduce chaos. Letting more Haitians enter lawfully has already worked to eliminate illegal Haitian border crossers and is also starting to work for Venezuelans. Expanding H-2 temporary guest worker visas for Mexicans had a similar effect before COVID. President Biden may have found a way around the catch-22 by taking lawful administrative action to reduce border chaos by channeling illegal crossers into a legal system.

Expanding legal immigration is the right policy, but it is also politically astute when doing so reduces chaos and thus builds more support for expanding immigration — or at least reduces the opposition. President Biden’s goal should be to Make Immigration Boring Again by transforming otherwise illegal border crossers into legal entrants. He’s taking some steps in that direction.

One response to my thesis above is that the government can get more control by building a wall, expanding enforcement, and saying really mean magic words. More enforcement is politically astute, which is why Biden's factsheet begins with changes to enforcement policy, but more enforcement is expensive and less effective than liberalizing legal immigration. Enforcement does deter illegal border crossers at an enormous cost. My former colleague Andrew Forrester and I estimate that in 2018:

[A]n additional 2,426 H‑2 visas issued to Mexicans would have cut the number of illegal Mexican immigrants apprehended by 1,584 – on average. The total cost to taxpayers of that would be zero, with an increase in total tax payments because the H‑2 workers would provide taxable goods and services in the United States. On the other hand, for the year 2018, these findings imply that hiring an additional 166 Border Patrol agents would have cut the number of Mexican apprehensions by 2,132 that year – at a total additional salary cost of $9,277,727 . . . American taxpayers can either pay $4,353 per additional Mexican apprehension in extra Border Patrol wages – which doesn’t include any of the other large costs of immigration enforcement – or decrease the numbers by issuing more H‑2 visas with a net‐positive fiscal impact.

More importantly for the perceptions of chaos theory, more enforcement would likely result in higher apprehensions and many more chaotic images. Even if more enforcement reduced apprehensions of illegal border crossers by 95 percent, many more pictures, documentation, and stories would feed the perception of chaos. Much easier and cheaper to divert would-be illegal immigrants into orderly legal immigration channels.

The Challenge to Classical Liberalism: No One Is Manning the Helm

Perceptions of chaos aren't just a problem for immigration liberalizers, they are a problem for classical liberalism in general. Deregulation is politically near-impossible amid economic chaos, even if bad regulations cause such chaos. People respond to chaos with demands for more government control which often increases chaos. Alcohol Prohibition provides an example of aligning the interests of politicians with a deregulatory agenda with a chaos-inducing policy in operation. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was able to end Prohibition because politicians wanted to raise tax revenue, not because they wanted to reduce crime and chaos through legalization.

FDR took office after a budget deficit of $2.7 billion in 1932. President Hoover's wasteful spending and the shortfall in revenue from the Great Depression left a big hole in the budget. Tax revolts on the state and local level warned FDR that the government couldn't raise existing taxes enough to balance budgets. Knowing deficits would be a problem, FDR and the Democratic Party opposed Prohibition to “provide therefrom a proper and needed revenue.” Federal alcohol taxes accounted for 12.6 percent of federal tax revenue, or over $483 million, in the year before Prohibition which would help plug the deficit. As an additional benefit, legalizing alcohol would reduce black markets and the attendant chaos. Homicide rates had spiked to 9.7 per 100,000 in the year of Prohibition’s repeal and fell 39 percent on the eve of Pearl Harbor.

Prohibition ended because the federal government wanted more tax revenue, not because everyone realized it boosted crime and chaos. But FDR got a two-fer from legalizing alcohol: less crime and more tax revenue. Crucially, the extra tax revenue is what convinced politicians to legalize alcohol. FDR was no classical liberal, and his administration was a disaster for the United States for multiple reasons, but we can learn from his successful effort to repeal Prohibition. His strategy offers a way for classical liberals to get around politically toxic chaos by incentivizing policymakers with the promise of more revenue. That's probably why drug legalization advocates talk so much about taxing drugs instead of how it would reduce chaos. I bristle at the suggestion because I don't want more taxes, but a legal and taxed market is better than an illegal and untaxed one, depending on the tax rates.

More profoundly, chaos is a problem for liberalism because of human perceptions and experiences. Every organization has somebody in charge. Businesses have bosses, school districts have superintendents, schools have principals, households have heads, gangs have a leader, and governments have a president, prime minister, general secretary, or somebody with a fancy title. Religious institutions differ in their organizations, but local churches and other houses of worship have leaders, and some religions have international management hierarchies. Looser and more informal organizations also have leaders, like groups of friends and extended families (the person who organizes holidays). Organizations have bosses to reduce principal-agent problems and align individual members' actions toward common goals, which require a manager to take credit for successes and suffer blame for failures. Humans seek higher status, and bosses are high-status, but almost everybody recognizes their importance in running organizations.

A political weakness of free-market classical liberalism is that there’s nobody in charge. There’s rarely somebody to blame. So, perceptions of chaos are aided by the very thing that makes spontaneous order such an effective organizing principle: There’s nobody in charge. Voters then see the chaos and demand more control, which the government obliges. That reaction frequently causes more chaos and problems, leading to calls for more control and onward in a viciously illiberal cycle. This is a challenge for free-market classical liberals, libertarians, and others opposed to more government control. The effects of proposed reforms on chaos and perceptions of chaos must consume far more attention than it does if we're going to be successful in liberalizing the economy.

The last paragraph reminds me of what Bryan Caplan called "the idea trap:" A bad government policy makes things worse, which causes people to demand more government. https://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/y2004/Caplanidea.html

Prohibition is an interesting example. You’re spot on that politicians respond to incentives as much as anyone; rather than the romanticized viewpoint that they are public servants making rational policy trade-off considerations to arrive at the most good for the most people. It’s nice when it works out that way.

Another interesting question is how much the perception of chaos at the border aligns with reality. On inequality, perceptions don’t seem to improve with actual improvements in living standards for people in the lower half of the income scale. Perhaps an important distinction here is that inequality is always a relative measure.