Review of The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move to A Lot Like the Ones They Left by Garett Jones, Part II

The Second Installment

In the first part of my review of The Culture Transplant, I discussed how author Garett Jones did not adequately evaluate the literature on trust and its relationship to prosperity. In this second part, I will explore other issues that Jones should have addressed more adequately and then consider the implications of his work. This post is less academic than my first post in this series, but there are still links to academic papers if you’re interested.

Deep Roots and What They Imply about U.S. Immigration Policy

Jones spends many pages explaining the findings of the deep roots literature and how they should guide immigration policy. In short, many of the papers in this literature find that the length of time a group’s ancestors lived under a state (S), lived with settled agriculture (A), and their level of technology at a point in the past (T) well predicts their GDP today – a score he dubs SAT. Jones then presents evidence that the level of T matters more than S or A, so his preferred measure gives much greater weight to T, producing the SAT*. The results are SAT and SAT* scores between 0 and 1, with higher numbers indicating deeper roots. In his appendix, Jones provides a helpful table of the SAT and SAT* scores per country. The result is that immigrants from countries with a higher SAT* are more likely to positively impact the economy than those with a lower SAT*.

The implication is that the U.S. should greatly liberalize or adopt a policy of free immigration with countries that possess a higher SAT*. Combining global population figures from 2021 with Jones’s appendix shows that 40 countries with a population of about 2.8 billion have a higher SAT* score than the United States – including developing countries like China, Brazil, Vietnam, and Russia. Countries with a higher SAT* than the United States account for 39 percent of the global population of countries that have an SAT* score. The global weighted average of the SAT* for the 88 countries available is 0.65, 0.08 less than the United States.

Using Jones's less preferred method of SAT, where each variable is equally weighted, shows that 36 countries with a population of 4.5 billion have a higher SAT score than the United States., equal to about 64 percent of the global population. That includes China, India, Pakistan, Brazil, and many other large developing countries. Jones could have easily framed the deep roots as evidence for more open immigration compared to the status quo.

As Bryan Caplan pointed out, there are three big outliers in the deep roots literature: China, India, and the United States. China and India should be much richer, and the United States should be poorer. Three outliers usually aren't an issue, except these are the three most populous countries in the world. Briggeman goes further by replicating the first major deep roots papers by Putterman and Weil (P&W). Briggeman’s article was published earlier this year, so Jones wasn’t able to mention it in his book, but it is an important replication and test of the deep roots. Briggeman weights by population and fills in missing data that caused several dozen countries to be dropped from P&W’s regressions. Briggeman finds P&W’s results are markedly weaker, the findings are not statistically significant, and the signs even flip in some cases. Jones discusses Caplan by arguing that Indian and Chinese economic performance was stymied by bad institutions until some decades ago and are now growing rapidly and catching up to where the deep roots predicted they would be. In another presentation, Jones elsewhere moves the goalposts in response to Caplan’s point.

Jones’s response is unsatisfying for three reasons. First, poor institutions in China and India were endogenous to the deep roots. The governments of China and India chose bad institutions and then eventually chose better ones. China is currently sliding back into more economic planning. What does a post hoc ergo propter hoc prove here? Does China's liberalization after the 1970s prove that the deep roots were right all along, or does China's current regression show it was wrong? What length of delayed development would be enough to say, "this theory isn't a great predictor in one the most populous country in the world"? Jones should have given readers a good theory of why long and variable lags are expected here. A bounded range would have been nice. A cross-sectional analysis would reveal very different answers if conducted in 1850, 1900, or 1950. The deep roots results seem heavily dependent upon the year of analysis and differences can persist for centuries, which are problems for a deep roots economic development theory.

Second, China's recent growth is likely greatly exaggerated if recent work by Martinez and others is to be believed, so maybe there is less catchup growth than Jones thinks.

Third, catchup growth doesn’t salvage deep roots. If the deep roots theory explains economic development, why does China need 40 years of catchup growth to be still poorer than what the deep roots literature would predict? Furthermore, the deep roots papers that Jones focuses on use income per worker, GDP per capita, or some other level measure of economic prosperity. But then Jones switches to growth, a trajectory measure, to deal with the outliers. Sure, the level measure is an accumulation of past growth, but that’s an inconvenient (but not totally undermining) shift that few readers would notice.

Despite the framing of Jones’s book as anti-immigration, the pro-immigration implication of his heavy reliance on the deep-roots literature is large. In another important paper that Jones ignores, Clemens and Pritchett used a SIR model to see how immigrants from countries with low total factor productivity (TFP) affect TFP in 1,185 census-defined Public Use Microdata Areas in the United States. One of their findings is that if all immigrants were from countries with TFP as low as Bangladesh, the annual flow of immigrants into the United States could be over 13 times higher than it currently is to maximize global economic gains from immigration – assuming very slow rates of assimilation.

Jones spends four pages responding to a working paper by Kelly that claims the findings of the deep roots literature are largely the result of statistical noise. Jones's response is a long-winded way of saying (my paraphrase) that “the statistical results that support my thesis are insignificant but less statistically insignificant than the results opposed to my thesis.” If Jones had undertaken a more thorough literature review, he likely would have found the paper by Voth that convincingly rebutted Kelly. Voth was published after my book on this topic, but I would have included his paper or at least cut out my summation of Kelly's paper. This is another example of a section of Jones’s book that would have been substantially different had he done a better job of reviewing the literature.

Jones’s book has an excellent section describing the often-brutal native backlash to Chinese immigrants and their descendants in Southeast Asia. This backlash includes anti-Chinese ethnic riots, periodic nationalizations of Chinese property, and anti-Chinese affirmative action. Jones rightly concludes that the benefit of economic growth from Chinese immigrants outweighs the downside of the occasional riot, as bad as that downside can be. In another paper, Jones argues that the populist political wins in the United States and Europe in 2016 were a native backlash to immigration. If native backlash is real and a mechanism that explains how immigration changes host countries, then it's the natives who change their societies by reacting poorly to immigrants. In that case, imported deep roots don’t matter much, and we should devote more time to examining how natives change in response to immigrants (there is a large literature on this, but these reviews are already too long).

Chinese Immigrants, The Doctrine of First Effective Settlement, and Exogenous Institutions

Jones discusses the positive economic impact of Chinese immigrants on the places where they settle. Jones even goes so far as to write that Chinese immigrants could help many poorer countries develop rapidly. Elsewhere, he praises the deep roots paper by Fulford, Petrov, and Schiantarelli (FFS) that examines how changes in ancestry composition are associated with changes in GDP per worker on the local level (county groupings) in the United States. But that paper finds that Chinese immigrants have a slightly negative impact on GDP per person. For instance, replacing 1 percentage point of county residents who have English ancestry with Chinese ancestry is associated with a -0.011 percent change in GDP per person. That’s a small magnitude, but still negative. In Table A-6 of FFS, replacing 1 percentage point of county residents with English ancestry with East Asian ancestry is associated with a -0.617 percent GDP per person. Jones should have reconciled his section on Chinese immigrants with the effects on Chinese immigrants on the county level in FSS.

Sub-Saharan African countries have the lowest SAT* scores by region of the world. This makes the section in FFS particularly interesting. They find that replacing 1 percentage point of county residents who have English ancestry with those who have African American ancestry leads to -0.709 percent GDP per worker. By African American, they specifically mean those long-settled Americans who are descended from enslaved Africans. However, that paper also finds that replacing 1 percentage point of county residents who have English ancestry with those who have African ancestry results in a +0.334 impact on GDP per worker. That's an aberrant result for the deep roots theory of migration but also an odd result for Jones's preferred trust mechanism, as African immigrants have slightly less trust than white native-born Americans. Perhaps the high levels of education and labor force participation among African immigrants can explain the difference, which is itself further evidence that immigrants aren’t a random sample of people from their home countries but are self-selected and selected by U.S. immigration policy.

Jones's examples of Chinese immigrants bringing productive cultural characteristics that grow economies where they settle is a better example of the Doctrine of First Effective Settlement (DFES) than his preferred cultural thesis. According to Wilbur Zelinsky, the DFES is

[w]henever an empty territory undergoes settlement, or an earlier population is dislodged by invaders, the specific characteristics of the first group able to effect a viable, self-perpetuating society are of crucial significance for the later social and cultural geography of the area . . . the activities of a few hundred, or even a few score, initial colonizers can mean much more for the cultural geography of a place than the contributions of tens of thousands of new immigrants a few generations later.

The DFES is consistent with observations that institutions are sticky, ontologically collective, and big changes occur because of major upheavals (invasion, conquest, revolution, etc.). The best example of such a large, rapid change is the European conquest of North America. Most of the American Indian inhabitants died from disease and violence, and the European settlers replaced the Native American population and institutions with European-origin immigrants and European institutions. This is an example of an actual Great Replacement rather than the hysterical nonsensical use of that term in the modern immigration debate.

In the centuries since the European conquest of North America, over 100 million immigrants have entered the territory of the United States and have largely slotted into the existing institutions. In other words, institutions are sticky and resilient. If everybody in Kentucky moved out of that state and 5 million French immigrants took their place, institutions in Kentucky would become much more French in a short period of time. But if 200,000 French immigrants moved there per year for 25 years, then there wouldn't be that much institutional change, even though the number of Frenchmen would be about the same.

A counterfactual thought experiment is helpful here. Imagine Europeans assimilated into the American Indian institutions rather than replacing them. This is a difficult-to-imagine counterfactual as it would require diseases to be less lethal to American Indians, closer technological parity between the two groups, and fewer wars of conquest, but it’s a useful thought exercise. Would European immigrants in that scenario displace and replace Native American institutions or would they assimilate into them? Assimilation would have dominated.

Another reason why you see little, if any, immigration-induced institutional change is that immigrants individually self-select to move. Immigrants are not a random sample of people from their home countries. Immigrants are the ones who choose to leave their country behind for economic opportunity. It would be weird to expect the people who emigrated to be the same as those who didn't – and indeed, they are different. If the story of multi-generational persistence of trust is true and immigrants are just a random sample of their home countries, then trust by ethnicity in the United States wouldn't be higher than it is in countries of origin. Indeed, this self-selection cuts both ways because those who leave for political reasons can impact government policy. The "Forty-Eighters,” liberal German immigrants to the United States who fought and lost in the Revolutions of 1848, weren’t a random sample of German immigrants and they had a large effect on U.S. politics in the leadup to the American Civil War. Nor are the Cuban, Venezuelan, or Vietnamese immigrants here today a random sample of people from those countries.

Singapore

Singapore and Hong Kong are good examples of the DFES providing a sticky and nonendogenous institutional environment that buttresses long-run economic growth. Singapore had an estimated population of about 1,000 Malays on the entire island when the British colonized it in 1819. The British established Singapore as a trading entrepôt to circumvent Dutch trading restrictions, instituting a policy of free trade that persists today. After colonization, Singapore's population grew rapidly due to immigration from China, India, and Malaysia, reaching almost 100,000 in 1871. Hong Kong became a British possession in 1841 and started with a population of roughly 6,000 that snowballed as political turmoil in China prompted much immigration, growing Hong Kong into another important entrepôt operating under a British policy of free trade that has largely persisted until today.

The British established economic institutions in Singapore and Hong Kong, and then many immigrants came from China who didn't change them, in Singapore's case, after it gained independence. Hong Kong's political institutions are worsening because of China's dominance, but the economic policies are largely persisting.

Still, it's a strange theory that says Chinese culture or deep roots spread economic prosperity except in China. Jones should have tried to explain why China is so poor (perhaps much poorer than we think, according to Martinez, 2022), why it has so consistently suffered from bad government, why economic institutions are so underdeveloped there, and why Chinese emigrants didn’t take actual-existing Chinese institutions with them. Immigrant self-selection and the differences between those who emigrate and those who stay behind could help explain this in Jones’s framework, but he doesn’t mention it. The colonies governed by British institutions attracted Chinese immigrants, maintained those institutions, and thrived.

Singapore is a fascinating case that stands against Jones's thesis. I will focus on Singapore because Jones calls The Culture Transplant the third book in his “Singapore Trilogy.” About 76 percent of Singapore's population is ethnically Chinese, and Hong Kong is about 92 percent Chinese, but Singapore's GDP per capita PPP (current international dollars) is 76 percent higher. “Can trust” responses to the trust question in Singapore and Hong Kong are about the same as the United States (slightly below compared to the U.S. GSS and slightly above compared to U.S. responses to the WVS). As a side note, both Hong Kongers and Singaporeans are about 30 percentage points less trusting than China according to the 2017-2022 WVS (further commentary on the trustworthiness of Chinese data?).

In 2017, Singapore’s foreign-born population was 47 percent – higher than the United States and any American city. From 1990 to 2015, the share of Singapore’s population from non-OECD countries increased from 15 percent of the population to 39 percent – a 25 percentage point swing in 25 years, by far the largest of any rich country. They comprised over 98 percent of Singapore’s foreign-born resident population. Most immigrants came from Malaysia, 19 percent from China, 7 percent from Indonesia, and 6 percent each from India and Pakistan. The weighted average SAT* of all immigrants in Singapore was 0.71, below Singapore’s 0.75. Of the 47 percent foreign-born resident population, 17 percentage points were naturalized Singaporeans or permanent residents, and 30 percentage points were temporary workers. Thirty-eight percent of Singapore’s workforce were temporary migrant workers in 2017.

The economic benefits of temporary migration are less than permanent immigration but substantially larger than current immigration restrictions. Singapore's guest worker policy would address some of Jones's concerns while allowing for a large stock of migrant workers, especially if the mechanism is immigrant-caused institutional change through voting. Guest workers wouldn't address Jones's concerns if there's some unidentified mechanism in the deep roots theory, trust, or some other vague cultural variable is the mechanism. As I mentioned before, if the United States had a temporary guest worker visa program on Singapore’s scale, there’d be about 100 million temporary guest workers here – at least 50 times higher than the current number. Jones’s admiration for Singapore’s intelligence and quality of government is obvious in his other books, so it’s a particularly glaring omission that he didn’t write about Singapore’s immigration and temporary migration policies.

Real Singapore and Synthetic Singapore

Singapore liberalized its immigrant laws beginning in 1981 in a series of reforms that ended in 1988. These reforms liberalized immigration of lower-skilled guest workers and higher-skilled permanent immigrants. Figure 1 tracks the change in the foreign-born share of Singapore’s population alongside real GDP per capita PPP. Real GDP per capita increased along with the migrant share of the population (they’re obviously endogenous). The remarkable thing is that so many relatively low-skilled guest workers did not reduce GDP per capita, which is likely given the large number of so many lower-skilled guest workers who are less productive than native Singaporeans.

Figure 1

Singapore Real GDP Per Capita PPP and Foreign-Born Share of the Population

Below, are a series of synthetic controls to see if this liberalization affected Singapore's GDP Per Capita PPP, Total Factor Productivity (TFP), and Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) score. In this case, the synthetic control method creates a Synthetic Singapore based on variables from a pool of other countries. I selected a pool that contained East and South East Asian countries, OECD countries, Hong Kong, former British settler colonies, and the United Kingdom. Interestingly, the results are very similar even when limited to East and South East Asia. Next, it then plots Synthetic and Real Singapore before and after Real Singapore liberalized its immigration laws in 1981. In theory, Real Singapore is what really happened and Synthetic Singapore is what would have happened had there been no policy change (you can read about the method here). My examples below are quick and dirty, but there is no statistically significant divergence between Real and Synthetic Singapores after liberalization for GDP Per Capita PPP (Figure 2), TFP (Figure 3), or EFW (Figure 4). Singapore liberalized immigration with no ill effects on two important economic variables and a measure of the quality of economic institutions.

Figure 2

Singapore GDP Per Capita PPP

Figure 3

Singapore Total Factor Productivity

Figure 4

Singapore Economic Freedom

There are several caveats about the synthetic controls above. First, they are simple – I put them together in about three hours. More complicated models may produce different results. Second, there are only a few other variables like population, EFW, the stock of immigrants, and the economic variables above. I may include other variables in future models. Third, synthetic controls allow causal inference, but simple models like these need to be built up to offer more causal inference.

Argentina – The Best Counterexample is Weak

Argentina is the best example of immigrants potentially undermining pro-growth economic institutions and culture. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Argentina grew rapidly to be one of the richest countries in the world. Then that suddenly changed in the early 20th century, and Argentina’s economic growth dramatically slowed. Jones presents a story of how immigrants from mostly Spain and Italy changed Argentina’s economic and political institutions, relying on a narrative from historical journals and encyclopedias. In this narrative, immigrants started the labor movement in Argentina, introduced more corruption, supported dirigiste economic policies, and ultimately backed Peronist dictatorship. Interestingly, the story about Argentina contradicts Jones’s deep roots theory.

As mentioned above, Jones’s preferred measure of the deep roots of persistence is a weighted average of state history (S), agricultural history (A), and technological history (T) that gives much greater weight to T than to S and A. The result is an SAT* score between 0 and 1, with higher numbers indicating deeper roots. In his appendix, Jones provides a useful table of the SAT* scores per country. According to his appendix, Argentina had an SAT* of 0.81 in 2002, which is lower than the SAT* for Italians and Spaniards, the two immigrant groups that he hypothesizes ruined Argentina's institutions 100 years ago. Italians have an SAT* of 0.82, and Spaniards have an SAT* of 0.96. Argentina must have had a score below both countries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries before those higher SAT* immigrants arrived from Italy and Spain. Weighting the SAT* score of all immigrants into Argentina by country of origin from 1915-1939 reveals them to have an SAT* of 0.87. As an aside, all countries included here have an SAT* higher than Singapore’s 0.75. In other words, Argentina followed what appears to be Jones's advice and allowed in large numbers of immigrants with a higher SAT* – and the results were disastrous according to him.

Moving beyond Jones’s narrative, a recent paper by Cachanosky, Padilla, and Gómez examined whether immigrants caused Peronism in Argentina, which is the proximate cause of Argentina’s subsequent moribund growth. They poke several holes in that theory and conclude that immigrants did not contribute to the rise of Peron but that long-settled Argentines from the countryside who moved to the cities were the primary supporters of Peronism. Domestic migrants from the countryside to the major cities formed the backbone of the working-class support for Peronism. Those native-born Argentine migrants came from rural regions and small towns where large landowners controlled political institutions through a patronage system. When changes in the global economy broke that rural economic system and the migrants came to Argentina’s cities, they brought patronage expectations with them and were electorally captured by local political elites – to say nothing of the impact of the Great Depression.

Thus, there is a potential domestic migration explanation that Jones could have used. International immigrants may have slowed the decline in Argentina’s political institutions by delaying the movement of rural Argentines to the cities where they became politically powerful. Although immigrants couldn’t vote because they had very low rates of naturalization, the second-and-third generations could, and they were solidly middle class and moving up the income ladder. The second-and-third generations were not the intended beneficiaries of Peronist policies, nor did they form their political support. The rot started among natives in the countryside and spread to the cities, meaning that Argentine institutions were always precarious. A similar tale could be told about Turkey and Iran.

Additionally, Argentina's political institutions were a lot weaker prior to mass immigration, as fraudulent election practices were the norm shortly after the 1853 constitution was adopted. Electoral reforms in the early 20th century concentrated more power in native Argentines of the older stock, inserted military supervision of elections, and began other domestic nation-building reforms that emphasized nationalistic education, military service, and indoctrination of Argentines into a cult of the nation. Furthermore, Argentina suffered a military coup in 1930 – not an uncommon occurrence in Latin America but the first in Argentina since the adoption of its 1853 constitution. Lastly, Italian and Spanish immigrants were 79 percent of immigrants, and both of their countries of origin had authoritarian regimes around that time. However, the allies conquered Italy's regime in World War II and replaced it with a more liberal government. Spain reformed its way out of authoritarianism and bad economic institutions beginning in the mid-1970s. Argentina is still languishing. In short, Argentina's political institutions were less stable, and old-stock Argentines were the source of authoritarian and dirigiste reforms that transformed Argentine institutions to be more similar to those in other Latin American countries.

Jones relies heavily on quotes from immigrant labor leaders and research by historians to make his case for Argentina. No doubt, those are interesting and important pieces of information. One could do something similar for the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where a large percentage of socialist intellectuals and labor union organizers were immigrants. For instance, 13 out of 15 daily socialist newspapers in the United States were printed in a language other than English at the time. However, the greatest electoral success of the Socialist Party prior to World War I were in states like Nevada, Oklahoma, Montana, and Arizona – ethnically homogeneous states with few foreign-born residents. In the election of 1920, the Socialist Party’s share of the vote fell everywhere except in the states of Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and Wisconsin – all states with heavy German immigrant and ethnic German populations. But a supposed innate predilection of Germans for socialism doesn’t explain why the Socialist Party's share of the vote remained high in places where they settled. It remained high because of residual anger by German Americans at the United States declaring war on Germany and the contemporaneous “Americanization” domestic policies that targeted the German language, German schools, and other markers of German culture. All data in this paragraph are on pages 200-202 of my book. Buy it here.

Jones Omits Most of the Literature on How Immigrants Affect the Institutions of Destination Countries

Jones ignored the only empirical peer-reviewed paper on how immigrants affected Argentina’s economic institutions. Beyond that, he also ignored a growing body of research on how immigrants affect institutions in destination countries. The general results of that research are that immigrants don't much affect these institutions, or immigrants improve them. Institutions are the rules of economic exchange and their enforcement mechanisms, such as property rights and contract rights. A widely used measure of institutional quality is the Economic Freedom of the World Index, which includes other policies such as trade, regulation, and currency stability.

I co-authored the first such paper on how immigrants affect institutions in destination countries with J.R. Clark, Bob Lawson, Benjamin Powell, and Ryan Murphy in 2015. We found no evidence that immigrants negatively impact economic institutions and some evidence of positive impacts. Endogeneity is a thorny concern here as immigrants go to prosperous countries that are prosperous thanks to productive institutions. Jones did write a criticism of our paper along with Ryan Fraser, which my co-author Ben Powell responded to.

We next looked at quasi-natural experiments of large exogenous immigration shocks in Israel and Jordan. Proper quasi-natural experiments eliminate endogeneity as a significant concern. The shock to Israel was the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which was not caused by Israel, and resulted in a 20 percent increase in Israel's population from immigration. The shock to Jordan was caused by Palestinians living in Kuwait, who mostly fled there in the year after Saddam Hussein's invasion in 1990, which increased Jordan's population by 10 percent. In both cases, the quality of economic institutions improved after the sudden surge of immigration. Our quasi-experimental methods allow us to make causal claims that immigrants are responsible for improved institutions in both cases. Still, there was also significant qualitative evidence to support the theory immigrants caused the improvement in institutional quality. There are several other papers on how immigrants affect institutions.

In our 2020 Cambridge University Press book, Wretched Refuse? The Political Economy of Immigration and Institutions, Benjamin Powell and I discussed the above papers and others on how immigrants affect corruption, terrorism, and the growth of government in American history.

In the United States, there is a strong inverse relationship between growth in the size of government and the immigrant population. More immigration is correlated with slower growth in government, and less immigration is correlated with faster growth in government. For example, federal expenditures as a percent of GDP rose by 303 percent from 1922 to 1967, when the borders were effectively closed. That period includes the creation of the New Deal and the Great Society programs. Growth in the size of government before and after that 45-year period has been much slower (Figure 5). Federal outlays don’t capture the growth in the regulatory state or other state actions that reduce economic freedom (like immigration restrictions), it’s merely the best proxy measurement that goes back over a century.

Figure 5

U.S. Immigrant Share of the Population and Real Federal Outlays Per Capita, 1900-2018

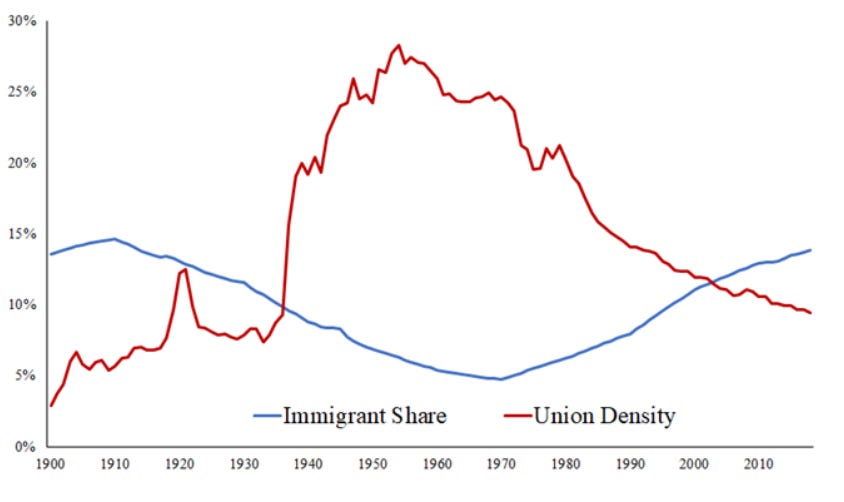

My hypothesized mechanism is that immigrants reduce government growth by undermining labor unions, the most effective groups pushing for larger government. In a working paper, we estimate that immigration since 1980 has been responsible for about 30 percent of the decline of unionization. It looks like immigrants might undermine the institutions that help grow the size of government, at least in the United States (Figure 6).

Figure 6

U.S. Immigrant Share of the Population and Union Density, 1900-2018

The Last Points

Jones didn't show that immigration undermines economic growth. He highlighted trust, deep roots, Argentina, and took snippets from a paper that contradicted his earlier statements about the benefits of Chinese immigration. But he did not link his findings to show that immigrants undermine prosperity. More original empirical work could have remedied that problem. Jones’s book is like a banana split without the banana.

In his earlier criticism of work by Clark, Powell, Lawson, Murphy, and me, Jones wrote that we didn’t show a simple scatterplot between immigrant stocks from poor countries and changes in economic freedom. Jones briefly mentioned economic freedom as an example of immigrant-induced institutional degradation. Figure 7 is a scatter plot of the change in the poor-country immigrant share of the population and the change in the Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) score for OECD countries, Singapore, and Hong Kong from 1990 to 2015. Countries without complete data were dropped. The EFW improved in most countries during that time, so the downward slope may give a more negative impression than is warranted.

Figure 7

Change in Poor Immigrant Share of Population and Change in EFW, 1990-2015

Figure 8 is a scatter plot of the change in immigrants from OECD countries as a share of the population and the change in the Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) score for OECD countries, Singapore, and Hong Kong from 1990 to 2015. Again, the scatterplot may give a negative impression because EFW improved in most countries in the sample.

Figure 8

Change in OECD Immigrant Share of Population and Change in EFW, 1990-2015

Figures 7 and 8 are simple scatterplots. They are not robust and people should not be convinced for reasons that Powell explained here. Eyeball econometrics cannot answer whether immigrants degrade institutions. In both cases, the regression results are slightly negative and insignificant. If you’ve followed Jones’s hypothesis until now, note that rich countries with larger increases in the immigrant share of the population from rich-country immigrants didn't see improvement.

Lastly, Puerto Rico. It’s an island and unincorporated U.S. territory in the Caribbean that the United States conquered from Spain in 1898. The United States has substantially influenced Puerto Rican institutions. Puerto Rico's constitution is modeled after the U.S. Constitution but also includes several socialistic and redistributionist provisions, reflecting the sentiments at the time of its adoption in 1952. Still, Puerto Rican economic institutions are far better than other Caribbean countries. Because of those better institutions and the U.S. government as an institutional backstop, Puerto Rico has the third highest GDP per capita in the Caribbean behind the Cayman Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands (Figure 9). Institutional quality and economic outcomes in Puerto Rico, while below the U.S. states, are far better than most places in the Caribbean. That's a wrinkle for the deep roots explanation of development.

Figure 9

Puerto Rico and the Caribbean GDP Per Capita, 2020

Conclusion

Jones's scholarly thoroughness in The Hive Mind and 10% Less Democracy didn’t migrate over into The Culture Transplant. Jones’s book makes a common point about immigration policy: Developed countries should select immigrants whose descendants are likely to assimilate better. However, he makes that point using research that is often unreliable or too broad to guide modern immigration policy – especially when governments can select on individual characteristics instead of relying upon the level of their ancestors’ technological development 500 years ago.

Great read.

Your emphasis on the importance of institutions made me think of charter cities: https://chartercitiesinstitute.org/

The possibility of lifting people out of poverty by creating new cities with good institutions for them to move to is really exciting, in my opinion. In line with DFES, perhaps it'd be smart to focus on getting the right founder population before opening up immigration.

Maybe the best way to accomplish all of this is to enshrine the idea of sanctuary cities as federal policy somehow, and create a legal framework by which individual cities can create guest worker programs. Taking both deportation and electoral participation off the table seems like a compromise both sides could agree on.

Would be great to redirect all of the energy around the controversy from Texas and Florida governors sending migrants to other states in a constructive direction.

I’m writing from a phone, so this will need to be brief.

1) COMMUNISM!

It’s really darn obvious that china was poor because it was wracked by external and internal war for a century and then wasted decades on communism.

All of us agree that war and totalitarianism can hold back a high iq people.

What can’t hold back a high iq people is a merely imperfect government or mild socialism. Most of the East Asian tigers were softish authoritarian, it didn’t matter.

China is obviously on track to be as rich as the other Asian tigers, it just takes time.

2) a review of Singapore would show a complete rejection of your thesis by LKY.

I also think it’s disingenuous to talk about “foriegn born”. A deep dive into Singapore’s population does not lead to the thesis (let’s import a billion low iq Africans or Arabs). A lot of Singapore’s foreign born are highly skilled professionals and Chinese ethnics.

3) I think we need to question whether western democracies can actually implement a two tiered apartheid state the way gulf monarchies or authoritarian Asian city states can

4) saying “X %” of the world population is meaningless as your mostly talking about first world countries l, and few people want to immigrate across first world countries.

Immigration is all about whether we let in more low iq third worlders.

6) the only significant source of high iq immigration is from China (some Indian subgroups have high iq but most Indians do t). This is a temporary state of affairs, and if they stay in China within a generation they will be in a high income country.

7) I wrote about this elsewhere but I think the idea that there is a “yellow man’s burden” to move to poor southeast Asian countries and become their smart fraction is flawed. Long run I think Chinese are better off staying in China, having a billion smart people contributing to human advancement is more important then having smart people waste h th die lives away trying to duck tape together third world countries.

8) with so many internal examples of immigrants changing things domestically in the west (just look at what blacks did to Detroit) I don’t know why this is a debate at all.

9) the answer to your question on th e USA is that non-whites pull down the average in the USA, but they are still a minority that can’t yet drag down our solid smart fraction (however, where they become a critical mass like in Detroit, they can)

10) iq would be better then jones obvious proxy for iq, but you know how it is