Testimony at House Hearing on Immigration Parole and Deportation

Trump's not trying to end illegal immigration. He wants immigration to be illegal.

This testimony was delivered July 15, 2025 at a joint hearing by the Homeland Security Committee subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and Accountability and the Subcommittee on Border Security and Enforcement entitled, “Case by Case: Returning Parole to Its Proper Purpose.”

Chairmen Brecheen and Guest, Ranking Members Thanedar and Correa, and distinguished members of the subcommittees, thank you for the opportunity to testify.

My name is David Bier. I am the Director of Immigration Studies at the Cato Institute, a nonpartisan public policy research organization in Washington, D.C. For nearly half a century, the Cato Institute has produced original research showing that a freer, more orderly, and more lawful immigration system benefits Americans. People are the ultimate resource. In a free country, immigrants can contribute to their new homes, making the United States a better, more powerful, and more prosperous place.

One legal way for immigrants to enter and participate in US society is parole, an immigration category first created by Congress in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. Over the decades since then, millions of individuals have entered this country as parolees. Although parole is a temporary status, it allows immigrants to adjust to lawful permanent residence if they are eligible through another pathway, which many thousands of parolees have done. Many former parolees are now Americans and continue to contribute to their new home. It is an essential and important feature of America’s legal immigration system.

Congress should:

- protect current parolees from the president’s mass deportation efforts;

- reinstitute the parole processes suspended by the president; and

- expand those processes to give more people a viable legal option to immigrate legally to the United States.

President Biden’s use of parole has deep historical precedent.

Although President Biden utilized parole in various important ways, his use of parole was not unique. The executive branch has implemented case-by-case categorical parole programs more than 126 times since 1952, when Congress created the parole authority.[1] Here are several noteworthy instances:

- Parole from detention (1954–1980): On November 12, 1954, Ellis Island and several other Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) detention centers were closed, and detainees were paroled into the United States. The number of detained immigrants decreased from a monthly average of 225 to less than 40.[2] Paroles were carried out under section 212(d)(5) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). The INS promulgated a regulation on January 8, 1958, authorizing this practice of parole from ports of entry rather than detention.[3] From 1954 until 1981, “most undocumented aliens detained at the border were paroled into the United States.”[4] Even after 1982, when the use of parole was narrowed, its use continued “when detention is impossible or impractical.”[5] The INS associate commissioner testified in 1964 that closing the detention facilities met the requirement of the parole statute because “it created a better image of the American Government and American public.”[6]

- Hungarian parole (1956–1958): On November 13, 1956, in response to the failed revolution against communists in Hungary, President Eisenhower ordered that 5,000 Hungarians be paroled into the United States.[7] On December 1, 1956, he increased the limit to 15,000 Hungarians before removing the cap entirely on January 2, 1957.[8] By June 30, 1957, 27,435 parolees had entered, totaling 31,915 by 1958.[9] For context, only 109 immigrants were admitted from Hungary in 1956, and just 321,625 immigrants were admitted worldwide. The Justice Department stated in 1957 that this was “the first time that the parole provision has been applied to relatively large numbers of people.” Several US charitable organizations helped prepare parole applications and assisted in finding housing and jobs for them.

- Cuban parole (1959–1973): Starting on January 1, 1959, following the communist revolution, the Eisenhower administration used parole to allow a “small percentage” of Cubans who had left the island and entered the United States illegally. By June 1962, the number of Cubans on parole increased to 62,500. Overall, about 107,116 Cubans were paroled into the United States from 1959 to 1965. Starting on December 1, 1965, based on a November 6, 1965 memorandum of understanding with the Cuban government, the Johnson administration operated daily “Freedom Flights” from Cuba to Miami.[10] During their operation, 281,317 Cubans were paroled into the United States.[11] At its peak in 1971, 46,670 Cubans arrived via parole,[12] compared to 361,972 total immigrants worldwide that year. Congressional appropriations funded the flights. In May 1972, the Cuban government suspended the flights, which were permanently terminated on April 6, 1973. The Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 made it possible for Cuban parolees entering after 1959, including future parolees, to adjust their status to legal permanent residents after two years in the US.

- Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian parole (1975–1980): On April 18, 1975, the president authorized a large-scale evacuation to Guam using parole. In FY 1975 alone, about 135,000 individuals received parole.[13] Congress funded (partially retroactively) the processing under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act.[14] In August 1975, the program was expanded to include Cambodians and Vietnamese with special connections to the United States, and on May 6, 1977, an additional 11,000 were authorized from Vietnam, Cambodia, or Laos.[15] From 1975 until mid-1980–when the Refugee Act was enacted and replaced the parole programs–more than 330,000 Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians were paroled into the United States.[16]

- Soviet/Moscow Refugee Parole (1988–present): In August 1988, the attorney general overturned the presumption that Soviet Jews qualified as refugees. On December 8, 1988, he established a “public interest” parole program for 2,000 Soviets each month who were denied refugee status.[17] Parolees needed to have sponsors in the United States and were not eligible for refugee benefits.[18] A total of 7,652 individuals were paroled in FY 1989.[19] About 17,000 Soviets were paroled from 1992 to 1998.

- Cuban Migration Accord paroles (1994–2003): On September 9, 1994, the United States and Cuba signed an agreement to pursue policies aimed at reducing illegal immigration, including the United States maintaining a minimum of 20,000 legal admissions of Cubans per year.[20] In order to meet this quota, the United States created the Special Cuban Migration Program to grant parole to about 5,000 Cubans annually through a lottery.[21] Around 75,000 Cubans were paroled under these programs from 1994 to 2003 (the last year for which statistics are available).[22]

- Cuban Wet Foot, Dry Foot parole (1995–2017): On May 2, 1995, the US government announced that it would not parole any Cubans intercepted at sea, even if within US waters, but it would parole anyone on US soil or arriving at a port of entry.[23] The INS and later Customs and Border Protection field manual stated that Cuban asylum seekers “may be paroled directly from the port of entry” except for those who “pose a criminal or terrorist threat.”[24] Subsequently, the number of Cubans paroled at ports of entry (mainly along the southwest border) increased significantly. From 2004 to 2016, 226,000 Cubans were paroled at US land borders.[25]

- Visa Waiver Program parole (2000): The authorization for the Visa Waiver Program expired in April 2000, so the Attorney General authorized all Visa Waiver Program entries under the parole authority.[26] Visa Waiver Program travelers were paroled into the United States from late April to September 2000 (approximately 8 million times).[27]

- Family Reunification Paroles (2007–2017, 2021–2025): On November 21, 2007, the DHS established a new parole program for any Cuban with an approved family-based petition for legal permanent residence. On December 18, 2014, DHS implemented a new parole program for any Haitian with an approved family-based immigrant visa petition if they have a priority date within two years of being current.[28] On August 2, 2019, DHS announced it would terminate the program but would extend the parole of current participants.[29] On October 12, 2021, it reversed its decision and continued the program.[30]

The Biden administration’s effort to use parole was not unique in purpose, approach, or volume. There is no basis for describing it as unprecedented or unlawful.

The statute envisions case-by-case categorical parole.

Allowing qualified immigrants to enter the United States using parole is unquestionably legal. Congress established this authority. Section (d)(5)(A) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) states:

“The Secretary of Homeland Security may… in his discretion parole into the United States temporarily under such conditions as he may prescribe only on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit any alien…”[31]

In 1996, Congress added the phrase “case-by-case basis,” and some people erroneously claim that “case-by-case” means that the Secretary of Homeland Security cannot designate any categories of people as eligible to apply for parole. However, that is obviously incorrect.

1. The Secretary of Homeland Security must define categories eligible to apply for parole. The statute does not specify the meaning of “urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit,” so the Secretary of Homeland Security needs to determine the categories of individuals who meet those requirements and will be considered for parole on a case-by-case basis. A case-by-case basis means that they are evaluated individually once they establish eligibility to apply. As the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) General Counsel explained in June 2001:

“Designating, whether by regulation or policy, a class whose members generally would be considered appropriate candidates for parole does not conflict with the ‘case -by-case’ decision requirement, since the adjudicator must individually determine whether a person is a member of the class and whether there are any reasons not to exercise the parole authority in the particular case.”[32]

2. Before 1996, categorical parole processes were administered on a case-by-case basis. Parole has historically been both categorical and case-by-case. The executive branch has ordered case-by-case categorical parole programs more than 126 times since 1952, when the parole authority was created.[33] For example, the Cuban Migration Accord of 1994 included a case-by-case requirement even though it created a new category eligible to apply.[34] This language was also used to describe parole decisions for Cubans in 1980 and Vietnamese in the 1970s.[35] If Congress had intended to eliminate all earlier categorical parole programs through the case-by-case language, it would not have used the same language that those programs had.

3. Congress specifically removed language in 1996 that limited parole to narrowly defined circumstances. The initial House version of the 1996 law that became the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act included language that defined “urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit,” but that bill never reached the floor of the House.[36] This was done in response to concerns that it denied the president “flexibility to deal with compelling immigration situations.”[37] Congress also removed a provision that would have banned the use of parole for people denied refugee status.

4. Congress has repeatedly demonstrated agreement with categorical uses of parole. For example, in 1966, Congress approved the adjustment of status to legal permanent residence for any Cuban paroled into the United States for over a year.[38] In 1996, even as Cubans continued to be paroled into the United States and as the law added terms like “case-by-case” into the parole statute, Congress affirmed that the Cuban Adjustment Act should remain in effect until Cuba has a democratically elected government.[39] That same year, it also provided an adjustment of status for Polish and Hungarian parolees.[40] In 2010, it extended this to include orphan parolees from Haiti.[41] In 2020, Congress expressed support for an ongoing parole program for relatives of US military members.[42] In 2021, it extended certain refugee benefits to Afghan parolees,[43] and in 2022, it did the same for Ukrainian parolees.[44]

The 2022–2024 parole processes were lawful and effective.

When the US government expanded the use of parole in 2022, the United States was experiencing levels of illegal crossings not seen in decades. As part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce illegal immigration, the United States was negotiating with many countries to decrease flows to the US borders.

- Ukrainian border parole at ports: In February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, leading tens of thousands of Ukrainians to come to the US-Mexico border seeking protection. Initially, Customs and Border Protection paroled the Ukrainians into the United States under section 212(d)(5)(A) of the INA.[45] In April 2022, approximately 20,102 Ukrainians were paroled into the United States from the southwest border.[46] This approach was clearly preferable to them crossing illegally and burdening Border Patrol.

- Uniting for Ukraine parole sponsorship: The administration rightly determined that it was even better for Ukrainians not to have to reach the US-Mexico border at all. On April 27, 2022, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) established the Uniting for Ukraine parole process. Through the U4U process, Ukrainians could apply for and obtain travel authorization in Europe and then fly to the United States to be paroled at airports, provided a US-based sponsor pledged to support them. The legal basis for this parole was the urgent humanitarian crisis caused by the invasion of Ukraine,[47] and no one challenged the action in court. The U4U process reduced Ukrainian arrivals at the US-Mexico border by over 99 percent.

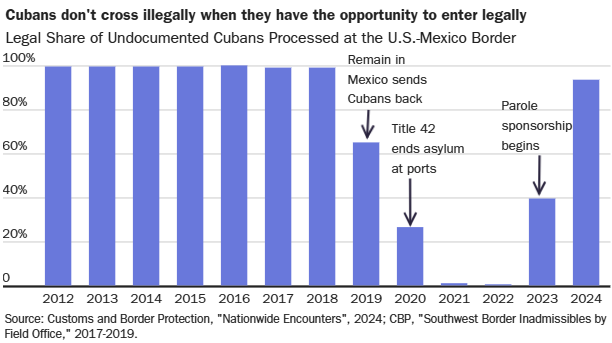

- Haitian border parole at ports: After evidence showed that US-Mexico ports of entry could handle higher flows of legal crossings of asylum seekers, the administration expanded access to ports for individuals referred to them by certain nonprofit organizations in 2022.[48] Haitians were the most represented among those using this new process. This is not surprising because Haitian asylum seekers had traditionally entered legally at the US-Mexico border until the Trump administration restricted and then eliminated their opportunity to do so.[49] Some states requested a district court to block this new parole process,[50] but it did not do so.[51] Within months of opening the ports to Haitians, about 99 percent of all Haitians arriving at the southwest border were no longer crossing illegally.

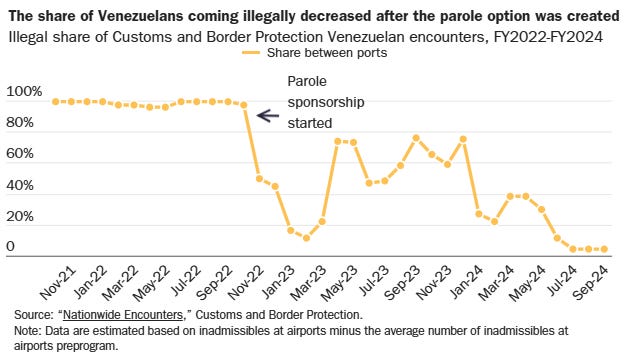

- Venezuelan parole sponsorship process: Following the success of Uniting for Ukraine, DHS expanded the parole sponsorship program to include some Venezuelans in October 2022.[52] The main reason was the significant public benefit of “enhancing the security of our border by reducing irregular migration of Venezuelan nationals.” The process initially lowered illegal immigration dramatically. However, because the process was capped at such a low number and there were so many displaced Venezuelans, it did not meet enough of the demand to stop illegal immigration from Venezuela. Due to the long delays in travel authorization that quickly developed, many Venezuelans could not be convinced to wait (despite efforts from some of their friends who did wait).[53]

Nonetheless, illegal immigration was lower than it would have been without the existing processes because many immigrants were diverted from crossing illegally. The Venezuelan experience highlights the need for Congress to establish durable, permanent options for legal migration so potential immigrants can credibly believe that these options will continue to exist.

- Parole sponsorship for Cubans and Nicaraguans: In January 2023, DHS announced the expansion of the Venezuelan parole process to include Cubans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans–collectively, this process is known as the CHNV parole process. Again, the primary “significant public benefit” the government cited was to reduce illegal immigration.[54] In December 2023, Cuban and Nicaraguan illegal immigration had reached an unprecedented level, but the parole process clearly and immediately had an enormous and sustained impact on Cuban and Nicaraguan illegal immigration.

It is not surprising that the Cubans quickly adopted the new process because they had historically always entered legally before the Trump administration terminated their right to request asylum at US-Mexico ports of entry. As with Haitians, President Trump created the problem of Cuban illegal immigration, which had never existed before at the southwest border, by banning the legal way for them to enter.

- Parole through the CBP One app: Alongside the expansion of the parole sponsorship process, the administration introduced a new system where anyone in Mexico could schedule an appointment to apply for parole at a port of entry using the CBP One mobile application.[55] Given that CBP had been denying asylum to those who crossed illegally, the CBP One appointment scheduling process was the only way for the United States to comply with sections 208 and 235 of the INA, which mandate processing immigrants for asylum.[56] CBP One had a limit of 1,450 appointments per day.[57] About 4.2 percent of CBP appointments did not result in parole.[58]

By the end of the Biden administration, the CBP One process became the main method for asylum seekers to enter the United States. As a result of CBP One and earlier Haitian nonprofit referral programs, over one million Haitians avoided having to cross the border illegally.[59] Due to the CHNV+U4U parole processes, nearly 780,000 immigrants avoided having to come to the border at all. Most CBP encounters from June to December 2024 involved people entering legally. By the end of Biden’s term, in December 2024, overall Border Patrol arrests were 33 percent lower than when he took office.[60]

By May 2024–before President Biden’s last major executive action on the border and before the suspension of the CHNV program–illegal entries were down:

- by 80 percent for Venezuelans from their pre-parole level (September 2022);

- by 96 percent for Nicaraguans from their pre-parole level (December 2022);

- by 98 percent for Haitians from their pre-parole level (May 2022); and

- by 99 percent for Cubans from their pre-parole level (December 2022).

Several states led by the State of Texas challenged these parole processes in court. In March 2024, judge ruled that Texas “has failed to prove that it suffered an injury-in-fact” because immigration to and through the state of Texas declined due to the success of the parole process.[61] In May 2024, the state of Texas later urged reconsideration in light of new facts, but the judge affirmed this ruling.[62]

Although these parole processes were categorical, even the Trump administration’s DHS agrees that “potentially eligible beneficiaries were adjudicated on a case-by-case basis.”[63] Moreover, the Trump administration’s DHS acknowledged that “these programs were accompanied by a significant decrease in CHNV encounters between southwest border POEs.”[64]

The parole processes were beneficial to the United States.

The parole processes did more than change the categorization of immigrants from legal to illegal. They also eased a heavy burden on Border Patrol, Customs and Border Protection, and state and local governments along the border.

- More predictable arrivals: For instance, in September 2021, CBP encountered nearly 18,000 Haitians who crossed en masse at a single location in Del Rio, Texas. The crossings overwhelmed Border Patrol’s processing capacity so much that they couldn’t bring them into custody them for almost two weeks. Immigration and Customs Enforcement was required to shift half of all deportation flights to Haiti for two weeks.[65] Everyone admitted through the CBP One app or via parole sponsorship must plan their arrival with CBP in advance, enabling CBP to predict when people will enter, which could have prevented the chaos in Del Rio but did prevent a reoccurrence.

- Pre-arrange transportation in advance: Border Patrol had to release people when its detention facilities reached capacity. Since individuals were released without notice and often without possessions, they couldn’t easily find transportation to their final destination, causing huge backups at bus stations. “We don’t have enough private bus seats to get everyone out,” McAllen, Texas City Manager Roy Rodriguez told The New York Post.[66] Under CHNV, immigrants would pay for commercial flights directly to their final destination.[67]

- Pre-arrange housing: Immigrants who entered illegally often did not know if they would be released or deported, so they had no way to secure housing in advance. Under CHNV, sponsors promised to help find housing for the parolees, and the parolees had time to arrange housing before they arrived.[68] Throughout the duration of the CHNV program, the Biden administration checked in with New York City, Boston, Chicago, and Denver–cities that had chosen to house migrants–to see if CHNV immigrants were arriving in significant numbers. They were not. In fact, one survey of CHNV arrivals found that only 3 percent relied on local organizations or the government for support.[69]

- Pre-arrange jobs: Another reason why CHNV parolees were likely not ending up in city shelters is that CHNV allowed parolees to immediately request authorization to work. Unlike those who entered illegally, CHNV and CBP One parolees could request employment authorization from DHS on their first day in the United States. Thanks to an act of Congress, U4U parolees didn’t need to request permission to start working legally.[70] Many immigrants in city shelters said they just wanted to work but were prohibited from doing so. “What I want the most is to work," an asylum seeker in New York named Patricia who was not paroled told CBS News.[71] Meanwhile, parolees quickly found jobs and began contributing to the United States.[72] One survey found that 88 percent of CHNV parolees intended to work once they received their permits.[73]

As of 2024, about three-quarters of a million parolees were already working in the United States, including 120,000 in construction, 120,000 in hospitality, and 90,000 in manufacturing.[74]

Due to increased immigration from people without traditional visas, such as asylum seekers, parolees, and illegal immigrants, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the US economy would be about $1.3 trillion larger in 2034 than it would have been without their contributions, and US federal debt held by the public would be nearly $1 trillion lower.[75] The CBO also estimated that parolees made up the majority of the workers providing these economic benefits.

The parole processes improved US security and vetting.

The parole processes improved vetting by allowing for more information checks prior to entry and for the implementation of enhanced screening for parolees.

1. Every parolee is subject to biometric and biographic background screening prior to entry. As DHS explained:

“There are distinct advantages to being able to vet more individuals before they arrive at the border so that we can stop individuals who could pose threats to national security or public safety even earlier in the process. The [CHNV] parole process will allow DHS to vet potential beneficiaries for national security and public safety purposes before they travel to the United States. As described below, the vetting will require prospective beneficiaries to upload a live photograph via an app. This will enhance the scope of the pre-travel vetting–thereby enabling DHS to better identify those with criminal records or other disqualifying information of concern and deny them travel before they arrive at our border, representing an improvement over the status quo.”[76]

2. The Biden administration implemented enhanced vetting for parolees. Parolee vetting includes checks against National Crime Information Center data, Terrorism Screening Dataset, INTERPOL, and other US government sources. The Biden administration improved vetting in two ways: First, as part of the Afghan, Ukraine, and CHNV parole initiatives, the Biden administration also expanded vetting for parolees to include screening against classified holdings for the first time from CBP’s National Vetting Center, subjecting them to more rigorous checks than other travelers and immigrants to the United States.[77] Second, it established recurrent continuous vetting against all the same US holdings after the parolees entered the country.[78]

3. The financial sponsor provided an additional check. The purpose of the financial sponsor was to provide the parolee with someone in the United States who could help them if needed. However, having this financial sponsor also added an additional layer of vetting for applicants. Approximately 18 percent of parole sponsors were denied by DHS.[79]

4. All applicants submitted their information online. For the first time in US immigration history, both applicants and sponsors submitted their information electronically, which enabled DHS to conduct unprecedentedly detailed fraud reviews of these processes.

DHS never concluded there was massive fraud within the parole sponsorship program.

In 2024, enabled by the thorough electronic vetting enhancement in the parole process, DHS finalized an analysis of potential fraud indicators among CHNV sponsor applications. This caused the administration to temporarily suspend processing until the investigation was completed.

- DHS fraud review did not conclude that there was “massive fraud.” Instead, it identified potential issues to investigate.

Repeat sponsors were permitted under CHNV. The main concern came from serial sponsors who had submitted dozens of applications for potential parolees. However, there was no limit to the number of individuals one could sponsor under the program.[80] Many of these sponsors were proud of their philanthropic efforts and did not hide them.[81] I personally know a wealthy individual who filed over 70 sponsor applications.

Typographical errors in big data aren’t a sign of fraud. I have personally worked with large datasets of user text input, and it is universally the case that some individuals enter physical addresses where mailing addresses should be, accidentally replace the letter “O” with the number 0, invert numbers while typing quickly, and make similar typos. Similarly, in the context of millions of applications, some people unintentionally click “yes” when they intended to click “no.” These errors are easily noticeable to someone reviewing them in context and are simply not evidence of fraud.

DHS did not set a baseline rate for fraud in immigration processes in general. There is no evidence to suggest that these processes experience more fraud than other immigration categories.

- DHS fraud review did not recommend ending the program. Instead, it suggested implementing additional protocols to better verify the identities of individuals submitting supporter applications and to investigate the problems.[82]

- DHS investigated the concerns and found no programmatic fraud problem. DHS reviewed over 70,000 concerning sponsor applications and referred just six for criminal investigation.[83] DHS concluded: “In the majority of cases, these indicators were ultimately found to have a reasonable explanation and resolved. For example, a supporter had entered a typographic error when submitting their information online.”[84] The Trump administration did not state that vetting was the reason for canceling the parole processes, and it has not identified any fraud.[85]

- DHS did not find any fraud concerns related to parolees. The issues it recommended investigating involved US sponsors who would be in the United States, regardless of whether the parole process was in place. DHS review concluded that it did not identify any “issues of concern relating to the screening and vetting of program beneficiaries.”[86] Law enforcement has no evidence of any criminal threat patterns related to CHNV parolees. During the first six months of the Trump administration, not a single person has been prosecuted for fraud related to the CHNV parole process.[87]

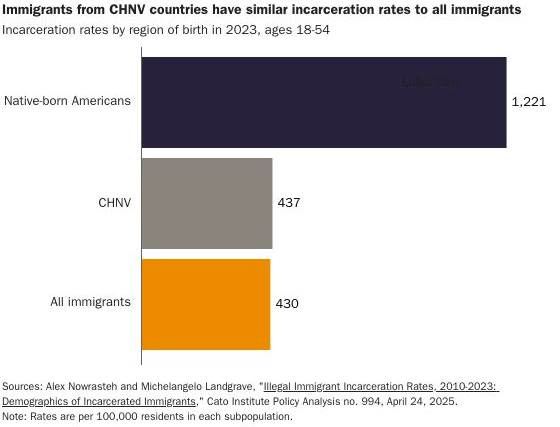

- CHNV nationals are less crime-prone than the US population. According to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, immigrants–legal and illegal–are less likely to have committed serious crimes that led to their incarceration in the United States than the average US-born person.[88] The incarceration rate for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans is also below the US-born average, meaning they help lower the crime and victimization rates for Americans.[89]

DHS’s indiscriminate deportation of parolees is unjustified and unjust.

Despite the success of the parole processes in reducing illegal immigration and integrating legal arrivals into the US labor market, the Trump administration immediately suspended all new entries under CHNV and CBP One–completely removing the scheduling functionality from the CBP One app.[90] This action stranded thousands of people who had already been accepted into those processes and canceled almost two million sponsorships by legal US residents.

- DHS is increasing illegal immigration by canceling CHNV and CBP One parole. On March 25, 2025, DHS announced it was canceling the parole of all CHNV parolees en masse.[91] DHS acknowledges that this abrupt cancellation of their parole will leave many parolees with “no lawful basis to remain in the United States,” thus increasing the number of people in the country illegally. On April 8, 2025, DHS revoked parole for nearly one million parolees who entered legally through the CBP One app.[92] It did not provide any public notice of the decision, nor did it follow the legal requirement to revoke parole only when the government determines that the purpose of the parole is complete.[93] The DHS Office of Inspector General found that DHS had no way to track parolees or confirm their lawful status, yet the department ended their parole early anyway.[94]

- DHS is carrying out indiscriminate arrests of parolees: The Trump administration is carrying out indiscriminate mass deportations of parolees who entered the United States legally under the Biden administration. DHS stated in its notice ending the parole that it “intends to remove promptly aliens who entered the United States under the CHNV parole programs,” even though this increases the department's burden compared to allowing them to leave voluntarily or continuing their parole.[95] This is diverting resources away from arresting public safety threats. ICE has arrested and imprisoned:

a Bronx high school student, Dylan Contreras, who entered legally using CBP One while attending his immigration court hearing.[96]

a six-year-old child with leukemia who had lawfully entered using the CBP One app and was attending his immigration court hearing with his mother.[97]

an Afghan who entered with parole and had a pending special immigrant visa application based on his long support for US military activities in Afghanistan.[98]

a 6-year-old boy and a 9-year-old girl who were paroled into the country with their mother were arrested and detained at their court hearing.[99]

- DHS illegally blocked parolees from receiving any other status for months. From February to June 2025, the Trump administration unlawfully delayed parolees' applications for permanent or temporary statuses to prevent them from getting an alternative status when it canceled their parole en masse in April and again in June.[100]

- DHS has stripped parolees of due process prior to removal. DHS is now expelling parolees through expedited removal without granting them a hearing in immigration court.[101] This means that any parolee in the country for less than two years receives no due process prior to removal and can be deported based solely on the decision of a low-level immigration agent. This decision violates numerous provisions of section 235 of the INA, which explicitly states that anyone “admitted or paroled into the United States” cannot be subject to expedited removal.[102] The law also explicitly prohibits applying expedited removal to anyone from a Western Hemisphere country that lacks full diplomatic relations with the United States, which includes all Venezuelans.[103]

- DHS is arresting parolees and sending them to prisons in Cuba and El Salvador. The Trump administration has already sent parolees who never violated any laws in the United States or elsewhere to Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba. For instance, Luis Alberto Castillo Rivera entered the United States on January 19, 2025, with a CBP One appointment but was sent to a prison in Cuba, even though he has no criminal record.[104] DHS has even been sending parolees to El Salvador’s notorious prison. For instance, former professional soccer player Jerce Reyes Barrios, who entered the United States via CBP One and has no criminal record in the United States or elsewhere, was illegally renditioned to El Salvador under the Alien Enemies Act in violation of a court order.[105]

How ending parole fits into the president’s mass deportation strategy

Ending parole typifies the four parts of President Trump’s mass deportation plan:

1. Cancel lawful status or citizenship to open as many people as possible to deportation. The widespread cancellation of parole demonstrates that mass deportation isn’t just about “illegal immigrants.” President Trump also intends to deport those here lawfully and American citizens. This includes:

terminating parole for 1.5 million people with parole;

allowing ICE agents to arrest parolees who still have valid parole;

banning asylum, and terminating Temporary Protected Status early for Venezuelans, Haitians, Afghans, Nepalese, Cameroonians, Hondurans, and Nicaraguans;[106]

arresting and detaining legal permanent residents and students;

attempting to deny the citizenship of US-born children of people without permanent residence or US citizenship.

2. Arrest based on convenience rather than threat. Arresting parolees shows how radically President Trump has deprioritized criminal threats to focus on already-vetted immigrants who haven’t committed any crimes in the United States but have made their presence known, making them easy targets.

On his first day in office, President Trump rescinded the requirement for Border Patrol and ICE to focus exclusively on recent border crossers and public safety threats.[107]

The White House set an arbitrary daily arrest quota, forcing ICE agents to prioritize noncriminals attending hearings over actual fugitives, requiring “quantity over quality,” as one ICE agent put it.[108]

The White House has mandated that ICE and Border Patrol stop creating lists of criminals to target and prioritize the arrest of immigrant workers who are going to their jobs, not committing crimes.[109]

By June, 71 percent of people booked into ICE’s detention facilities this year were individuals without criminal convictions–just 7 percent had violent criminal convictions–and nearly half have no pending charge either.[110]

ICE is currently arresting six times as many immigrants without any criminal convictions as they did in 2017–6,000 per week.[111]

3. Deport without due process. The treatment of parolees is emblematic of the third aspect of the administration’s mass deportation agenda.

Dozens of parolees who entered the United States legally were among the Venezuelans that the administration illegally transported to El Salvador in March, using the Alien Enemies Act.[112] Altogether, 50 legal immigrants, including four refugees, were sent to El Salvador without proper due process.[113]

The Trump administration also expanded the use of expedited removal into the interior of the United States, allowing low-level ICE agents to order people removed from the country without a hearing.[114] This expansion violated the Administrative Procedure Act because the administration refused to allow any notice and public comment.[115] Moreover, it is illegal as applied to parolees who are specifically excluded from its use,[116] and it cannot legally be applied to all Venezuelans because their government does not have full diplomatic relations with the United States.[117] Yet the administration is subjecting parolees and Venezuelans to expedited removal anyway.

4. Divert resources from more important law enforcement agencies. The Trump administration is redirecting up to Border Patrol, Homeland Security Investigations, up to 80 percent of the ATF agents, 25 percent of the DEA, thousands of FBI agents, and many other criminal law enforcement officers away from their criminal investigations to focus on low-level immigration enforcement.[118] These cases include human trafficking, child exploitation, cybercrime, weapons export controls, intellectual property theft, and drugs. DEA admits its agents don’t know how to handle immigration enforcement,[119] and last month, the FBI decided it needed some of those terrorism investigators after all, effectively admitting it had irresponsibly compromised national security.[120]

The Committee should investigate President Trump’s unconstitutional actions.

Although President Biden’s use of parole was unquestionably lawful, President Trump has been involved in serious violations of the US Constitution since the very first day of his presidency. President Trump is now attacking the First, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Tenth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution, and the right of habeas corpus. The Committee has a responsibility to investigate these and other abuses.

- President Trump declares that he is above US law. On his first day in office, President Trump signed an executive order that purports to allow him to suspend all US immigration laws, which would deny due process to those accused of entering the country illegally.[121] He states that he has “inherent powers to control the borders of the United States” that supersede US immigration law.

- President Trump asserts the power to suspend the First Amendment. The Trump administration has repeatedly detained individuals, including lawful permanent residents, for exercising their free speech rights in the United States.[122] The government has been clear that these actions were not connected to any criminal acts,[123] and it has also arrested students for coauthoring opinion articles criticizing a foreign country’s military actions, such as Fulbright scholar Rumeysa Ozturk from Tufts University.[124]

- President Trump asserts the power to deny US-born Americans their citizenship. On his first day in office, President Trump declared that Americans born in the United States to people without legal permanent resident status were not US citizens–in direct violation of the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution.[125] Fortunately, courts have temporarily blocked this unconstitutional action.[126]

- President Trump is violating the 4th Amendment by engaging in blatant illegal profiling. White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller has ordered ICE agents not to “develop target lists of immigrants suspected of being in the US illegally” and to “just go out there and arrest illegal aliens” by targeting people perceived to be illegal immigrants.[127] White House immigration czar Tom Homan has said agents will use “occupation, location, physical appearance,” and refusal to speak with agents to detain people–none of which, separately or together, imply that someone is in the country illegally.[128]

Agents are arresting 1,100 percent more people with criminal convictions on the streets than during the first Trump administration in 2017, nearly 4,000 per week–impossible without illegal profiling.[129]

Agents pepper-sprayed and tackled a father of three Marines because, according to Border Patrol’s own account, he “refused to answer questions” after agents stopped to interrogate him as he did yardwork.[130]

Agents tackled a man, and then, when he told them in English that he was a US citizen, they left.[131]

A US citizen man working at a car wash was arrested and transferred off-site, despite providing identification and claiming US citizenship.[132]

Border Patrol carried out an operation that involved profiling Hispanic farm workers–something not disputed by Border Patrol–and one court found that these stops are likely violating the 4th Amendment of the Constitution.[133]

Border Patrol and ICE conducted those same operations in Los Angeles, and another court has blocked them.[134]

DHS claims it is not conducting any profiling operations, but it is still appealing the ruling that blocks it from doing so.[135]

- DHS is detaining parolees, including children, in inhumane and unconstitutional conditions. It is unconstitutional to detain civil immigration detainees in conditions that violate the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution or are worse than those for criminal detainees under the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.[136] At the end of June, ICE was detaining 57,861 individuals, even though Congress had only appropriated money to detain 41,500.[137] ICE was forcing people to sleep on floors.[138] At least 13 people have died in ICE facilities this year through July, already exceeding the total for FY 2024.[139]

Here is one detainee’s description: “There was one toilet for 35 to 40 men, who had no privacy when using it, he said. They slept on the concrete floor in head-by-toe formation with aluminum blankets to cover them. He lost seven pounds in six days, he said, because the food was poor and the portions tiny. “It was so bad,” he said, “I used water to drink it down.” Mr. Gomes said he was not able to shower or change his clothes the entire time he was there.”[140]

One court summarized: One ICE facility “does not have beds, showers, or medical facilities. Individuals are being kept in small, windowless rooms with dozens or more other detainees in cramped quarters. Some rooms are so cramped that detainees cannot sit, let alone lie down, for hours at a time.”[141] A person with cancer was being denied access to chemotherapy there.[142]

- President Trump is attempting to coerce state governments unconstitutionally. He has issued an executive order that tries to block all federal grants to municipalities that do not allocate their resources to support ICE.[143] His administration has sued Illinois and Chicago for refusing to cooperate with ICE, asserting that the president can mandate that they do what he wants.[144] His Department of Justice (DOJ) has issued a memorandum requiring criminal investigations into state and local officials who fail to cooperate with the federal government.[145] These actions clearly violate the Tenth Amendment, which protects states from being commandeered by the federal government.

- President Trump asserts the power to suspend due process. President Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act to remove Venezuelans and Salvadorans without allowing them the opportunity to contest their removability in immigration court. This invocation is clearly illegal because the Alien Enemies Act only applies during a time of war, and the United States is not at war, according to his own CIA director.[146] The Supreme Court has already ruled that these deportations violated the constitutional due process rights of the removed individuals.[147]

- President Trump asserts the power to order imprisonment without charge or trial. President Trump’s purpose for invoking the Alien Enemies Act was to rendition people–including some with lawful statuses in the United States–to a mega-prison in El Salvador. For instance, the administration deported a refugee who was vetted abroad and legally entered the United States under the refugee program to an El Salvador prison without charging them with a crime.[148] Ordering someone imprisoned without charge, trial, and conviction is unconstitutional.[149] The government admits that “many” (probably most) of the individuals sentenced to prison in El Salvador at US taxpayer expense have not committed any crime anywhere.[150] The administration claims that they are members of a Venezuelan gang based on their tattoos, but Venezuelan gang experts and US government agencies have repeatedly debunked the idea that Venezuelan gangs have distinctive tattoos.[151] Even if they did, that would not remove the Constitution’s requirement that no person can be subject to punishment without due process.[152]

- President Trump ignores court orders. When President Trump was caught trying to illegally remove people under the Alien Enemies Act, the judge ordered DHS to stop the removals and return flights to the United States.[153] DHS chose to ignore him instead.[154] In a second case, the administration illegally deported a Salvadoran man to El Salvador, even though he had been granted withholding of removal by an immigration judge barring his removal to El Salvador. A court ordered DHS to bring him back, but the administration not only refused to comply–it also placed on leave the US attorney who admitted the error in court.[155] This has become part of a pattern where the administration is ordered by courts to stop illegal actions, but it refuses to comply until it is convenient for them or after they are caught violating the orders.[156] Congress should investigate these violations and determine further ways to force the executive branch to follow court orders.

Immigrants–especially legal immigrants–make the United States a wealthier, freer, and safer place to live. The US government should encourage people to immigrate to the United States legally, including through parole. Parole has been an essential component of America’s legal immigration system for over seven decades, and should remain so in the future.

Endnotes

[1] David J. Bier, “126 Parole Orders over 7 Decades: A Historical Review of Immigration Parole Orders,” Cato at Liberty (blog), July 17, 2023.

[2] Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, US Department of Justice, 1956.

[3] Fed. Reg. Volume 23 Number 5, January 8, 1958.

[4] “Highlights of Selected Recent Court Decisions,” I&N Reporter, October 1957.

[5] Hearing on Detention of Aliens in Bureau of Prison Facilities, Before the Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Courts, Civil Liberties, and the Administration of Justice, 97th Cong. 2nd Sess. ( June 23, 1982).

[6] Study of Population and Immigration Problems, Before the Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee No. 1, (May 15, 1963) (statement of Mario T. Noto, Associate Commissioner, Immigration and Naturalization Service, U.S. Department of Justice).

[7] Annual Report of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, US Department of Justice, 1957.

[8] Page 162, Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 85th Cong. 1st. Sess. 1957.

[9] LeMont Eaton, “Hungarian Parolee Inspection Program,” I&N Reporter, April 1960.

[10] “Cuba and United States: Agreement on Refugees,” International Legal Materials 4, no. 6 (1965): 1118–1127.

[11] Charlotte J. Moore, “Review of U.S. Refugee Resettlement Programs and Policies. A Report. Revised,” Congressional Research Service, 1980.

[12] Charlotte J. Moore, “Review of U.S. Refugee Resettlement Programs and Policies. A Report. Revised,” Congressional Research Service, 1980.

[13] Refugee Admissions by Region, Fiscal Year 1975 through September 30, 2022, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, October 5, 2022.

[14] The Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975, Pub. L. 94–23, 94th Cong. 2nd Sess., May 23, 1975.

[15] Elmer B. Staats, “Domestic Resettlement of Indochinese Refugees: Struggle for Self-Reliance,” Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, May 10, 1977.

[16] “Hearings, Reports, and Prints of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary,” US Government Printing Office, 1980.

[17] Ruth Marcus, “U.S. Moves to Ease Soviet Emigres’ Way,” Washington Post, December 8, 1988.

[18] Hearings on Foreign Operation, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations for 1990, Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, 101st Cong., 1st Sess. (1989).

[19] Hearing on U.S. Refugee Programs for 1991, Before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 101st Cong., 2nd Sess. (October 3, 1990).

[20] “Migration and Refugees,” Communique between the United States of America and Cuba, September 9, 1994.

[21] Immigration and Naturalization Service, "INS ANNOUNCES SECOND CUBAN MIGRATION PROGRAM," 73 No. 11 Interpreter Releases 319 Interpreter Releases, Thomson Reuters Practical Law March 18, 1996.

[22] David J. Bier, “126 Parole Orders over 7 Decades: A Historical Review of Immigration Parole Orders,” Cato at Liberty (blog), July 17, 2023.

[23] President William J. Clinton, “Joint Statement with the Republic of Cuba on the Normalization of Migration”, May 2, 1995.

[24] Inspectors Field Manual, Part A, US Customs and Border Protection, 2010.

[25] David J. Bier, “126 Parole Orders over 7 Decades: A Historical Review of Immigration Parole Orders,” Cato at Liberty (blog), July 17, 2023.

[26] Abigail F. Kolker, “Visa Waiver Program,” Congressional Research Service, October 15, 2024.

[27] “2000 Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service,” Department of Justice, September 2002.

[28] “Implementation of Haitian Family Reunification Parole Program,” US Citizenship and Immigration Services, December 18, 2024.

[29] “USCIS to End Certain Categorial Parole Programs,” US Citizenship and Immigration Services, August 2, 2019.

[30] “The Haitian Family Reunification Parole (HFRP) Program,” US Citizenship and Immigration Services, October 12, 2021.

[31] 8 U.S.C. 1882(d)(5)(A))

[32] “Expert Declaration of Yael Schacher,” Civil Action No. 6:23-CV-00007, United States District Court, Southern District of Texas, Victoria Division, June 20, 2023.

[33] David J. Bier, “126 Parole Orders over 7 Decades: A Historical Review of Immigration Parole Orders,” Cato at Liberty (blog), July 17, 2023.

[34] “U.S. Response to the 1994 Cuba Migration Crisis,” US General Accounting Office National Security and International Affairs Division, September 1995.

[35] P. 38, Hearing on Caribbean Refugee Crisis, Cubans, and Haitians, Before the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, 96th Cong., 2nd Sess. (May 12, 1980).

[36] H. R. 2202, “Immigration Control and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1996,” 104th Cong., 1st Sess., August 4, 1995.

[37] “Immigration in the National Interest Act of 1995,” 104th Cong., 2nd Sess., March 4, 1996.

[38] initially 2 years.

[39] Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations Act, Pub. L. 104–208, September 30, 1996.

[40] P.L. 104–208, providing for adjustment of status of Polish and Hungarian parolees.

[41] Help HAITI Act of 2010 (P.L. 111–293), providing for adjustment of status of Haitian orphan parolees.

[42] The National Defense Authorization Act of 2020 (P.L. 116–92), expressing congressional support for an ongoing parole program for relatives of U.S. military members.

[43] The Extending Government Funding and Delivering Emergency Assistance Act of 2021 (P.L. 117–43), providing refugee benefits to Afghan parolees, explicitly appropriating money for those benefits, and directing the creation of a plan to process Afghan parole applications.

[44] The Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2022 (P.L. 117–128), providing refugee benefits to Ukrainian parolees.

[45] Kevin Sieff, “There are new migrants on the U.S.-Mexico border: Ukrainian refugees,” Washington Post, April 2, 2022.

[46] “Nationwide Encounters,” US Customs and Border Protection, last modified March 13, 2025.

[47] Implementation of the Uniting for Ukraine Parole Process, Department of Homeland Security, April 27, 2022.

[48] “Fourth Declaration of Blas Nuñez-Neto,” Arizona v. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, November 10, 2022.

[49] David J. Bier, “How the U.S. Created Cuban and Haitian Illegal Migration,” Cato at Liberty (blog), February 15, 2022.

[50] David J. Bier, “Some States Are Fighting in Court to Increase Illegal Immigration,” Cato at Liberty (blog), November 2, 2022.

[51] State of Louisiana v. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, November 14, 2024.

[52] “An Implementation of a Parole Process for Venezuelans,” Department of Homeland Security, October 19, 2022.

[53] Julie Turkewitz, “She Heeded Biden’s Warning to Migrants. Will She Regret It?” New York Times, October 24, 2023.

[54] “Implementation of a Parole Process for Cubans,” Department of Homeland Security, January 9, 2023.

[55] “DHS Scheduling System for Safe, Orderly and Humane Border Processing Goes Live on CBP One™ App,” Department of Homeland Security, January 12, 2023.

[56] 8 U.S.C. §1225; 8 U.S.C. §1158

[57] “Fact Sheet: CBP One Facilitated Over 170,000 Appointments in Six Months, and Continues to be a Safe, Orderly, and Humane Tool for Border Management,” Department of Homeland Security, August 3, 2023.

[58] “New Documents Obtained by Homeland Majority Detail Shocking Abuse of CBP One App,” Homeland Security Republicans, October 23, 2023.

[59] Immigration Enforcement and Legal Processes Monthly Tables, Office of Homeland Security Statistics, last updated January 16, 2025.

[60] Testimony of David J. Bier, Director of Immigration Studies at the Cato Institute, Before the Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Integrity, Security, and Enforcement, January 22, 2025.

[61] “Memorandum Opinion and Order,” State of Texas v. United States Department of Homeland Security, March 8, 2024.

[62] “Memorandum Opinion and Order,” State of Texas v. United States Department of Homeland Security, May 28, 2024.

[63] “Termination of Parole Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans,” Department of Homeland Security, March 25, 2025.

[64] See footnote 34, “Termination of Parole Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans,” Department of Homeland Security, March 25, 2025.

[65] Thomas Cartwright, ICE Air Flights, September 2021 and Last 12 Months, Witness at the Border, October 8, 2021.

[66] Marie Banks, “‘Not enough seats’: Buses leaving Texas border town packed with illegal migrants,” New York Post, July 22, 2021.

[67] “CBP Releases December 2024 Monthly Update,” Customs and Border Protection, January 14, 2025.

[68] Marcela García, “Haitians are desperately looking for sponsors in Boston,” Boston Globe, March 3, 2023.

[69] “Survey data show the administration’s parole policy for the Americas is a successful model for new legal pathways,” fwd.us, January 25, 2024.

[70] “Work Authorization for Ukrainians–Uniting for Ukraine Program,” Reddy Neumann Brown PC, November 22, 2022.

[71] Camilo Montoya-Galvez, “As cities struggle to house migrants, Biden administration resists proposals that officials say could help,” CBS News, August 22, 2023.

[72] “Survey data show the administration’s parole policy for the Americas is a successful model for new legal pathways,” fwd.us, January 25, 2024.

[73] “Survey data show the administration’s parole policy for the Americas is a successful model for new legal pathways,” fwd.us, January 25, 2024.

[74] “Industries with critical labor shortages added hundreds of thousands of workers through immigration parole,” fwd.us, March 26, 2025.

[75] “Effects of the Immigration Surge on the Federal Budget and the Economy,” Congressional Budget Office, July 2024.

[76] “Implementation of a Parole Process for Haitians,” Department of Homeland Security, January 9, 2023.

[77] “Uniting for Ukraine, Process Overview and Assessment,” Homeland Security Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans, November 4, 2024.

[78] “DHS Has a Fragmented Process for Identifying and Resolving Derogatory Information for Operation Allies Welcome Parolees,” DHS Office of the Inspector General, May 6, 2024.

[79] “Shock and Awe: Internal Homeland Security Report Proves that the Biden-Harris-Mayorkas CHNV Parole Program is Loaded with Fraud,” Federation for American Immigration Reform, August 2024.

[80] David Bier and Alex Nowrasteh, “Biden’s DHS Halting Migrant Program Raises Border Security Concerns,” Reason, August 9, 2024.

[81] Gisela Salomon, Elliot Spagat, and Amy Taxin, “Message from US asylum hopefuls: Financial sponsors needed,” Associated Press, January 6, 2023.

[82] Julia Ainsley, “Biden administration to restart immigration program that was paused over fraud concerns,” NBC News, August 29, 2024.

[83] Julia Ainsley and Laura Strickler, “Biden administration may soon restart immigration program that was paused for possible fraud,” NBC News, August 28, 2024.

[84] Julia Ainsley, “Biden administration to restart immigration program that was paused over fraud concerns,” NBC News, August 29, 2024.

[85] “Termination of Parole Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans,” Federal Register Volume 90 Number 56, March 25, 2025.

[86] Julia Ainsley, “Biden administration to restart immigration program that was paused over fraud concerns,” NBC News, August 29, 2024.

[87] “Declaration of Kika Scott,” Svitlana Doe, et al., vs Kristi Noem, et al., July 1, 2025.

[88] Michelangelo Landgrave and Alex Nowrasteh, “Illegal Immigrant Incarceration Rates, 2010–2023,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 994, April 24, 2025.

[89] Alex Nowrasteh, “Haitian Immigrants Have a Low Incarceration Rate,” Cato at Liberty (blog), July 7, 2025.

[90] Thomas Graham, “US asylum seekers in despair after Trump cancels CBP One pp: ‘Start from zero again’,” The Guardian, January 23, 2025;

“Plaintiffs’ Reply in Support of Motion for Temporary Restraining Order,” Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center, et al. v. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, et al., January 29, 2025.

[91] See footnote 4, “Termination of Parole Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans,” Department of Homeland Security, March 25, 2025.

[92] Ali Bianco, “DHS revokes parole for hundreds of thousands who entered via the CBP One app,” Politico, April 8, 2025.

[93] “Opinion and Order Granting Petition for Habeas Corpus,” Case No. 3:25-cv-965-SI, July 9, 2025; “Memorandum & Order Granting in Part Plaintiffs’ Emergency Motion for a Stay of DHS’s En Masse Truncation of All Valid Grants of CHNV Parole,” Civil Action No. 1:25-cv-10495-IT, April 14, 2025.

[94] US Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General, “DHS Needs to Improve Oversight of Parole Expiration for Select Humanitarian Parole Processes,” July 2, 2025.

[95] See footnote 4, “Termination of Parole Processes for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans,” Department of Homeland Security, March 25, 2025.

[96] Briana Scalia, “NYC public school student detained by ICE: Who is Dylan Contreras?” FOX5 New York, May 30, 2025.

[97] Corky Siemaszko, “6-year-old Honduran boy with leukemia who had been seized by ICE is back in L.A.,” NBC News, July 4, 2025.

[98] Madeleine May and Hannah Marr, “Afghan ally detained by ICE after attending immigration court hearing,” CBS News, July 1, 2025.

[99] Hallie Golden, “Family sues over US detention in what may be first challenge to courthouse arrests involving kids,” Associated Press, June 27, 2025.

[100] Camilo Montoya-Galvez, “U.S. pauses immigration applications for certain migrants welcomed under Biden,” CBS News, February 19, 2025; “Declaration of Kika Scott,” Svitlana Doe, et al., vs Kristi Noem, et al., July 1, 2025.

[101] “Designating Aliens for Expedited Removal,” Department of Homeland Security, January 21, 2025.

[102] 8 USC §1225 (b)(1)(A)(iii)(II) (2025).

[103] 8 USC §1225 (b)(1)(F) (2025); Jennifer Hansler, “Venezuelan embassy run by opposition in US closes after Guaido ouster,” CNN.com, January 6, 2023.

[104] “Declaration of Luis Alberto Castillo Rivera,” Center for Constitutional Rights, March 1, 2025.

[105] Armando Garcia, “Man deported to El Salvador under Alien Enemies Act because of soccer logo tattoo: Attorney,” ABC News, March 20, 2025.

[106] Juliana Kim, “DHS ends Temporary Protected Status for thousands from Nicaragua and Honduras,” NPR.com, July 7, 2025.

[107] President Donald J. Trump, “Protecting the American People Against Invasion,” The White House, January 20, 2025.

[108] Jennie Taer, “Trump admin’s 3,000 ICE arrests per day quota is taking focus off criminals and ‘killing morale’: insiders,” New York Post, June 17, 2025.

[109] Elizabeth Findell et al., “The White House Marching Orders That Sparked the L.A. Migrant Crackdown,” Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2025.

[110] David J. Bier, “ICE Is Arresting 1,100 Percent More Noncriminals on the Streets Than in 2017,” Cato at Liberty (blog), June 24, 2025.

[111] David J. Bier, “ICE Is Arresting 1,100 Percent More Noncriminals on the Streets Than in 2017,” Cato at Liberty (blog), June 24, 2025.

[112] David J. Bier, “50+ Venezuelans Imprisoned in El Salvador Came to US Legally, Never Violated Immigration Law,” Cato at Liberty (blog), May 19, 2025.

[113] David J. Bier, “50+ Venezuelans Imprisoned in El Salvador Came to US Legally, Never Violated Immigration Law,” Cato at Liberty (blog), May 19, 2025.

[114] “Designating Aliens for Expedited Removal,” Federal Register Volume 90 Number 15, January 24, 2025.

[115] “Plaintiffs’ Reply in Support of Motion for a Stay of Agency Action Under 5 U.S.C. § 705 to Preserve Status and Rights,” Case No. 1:25-cv-0872, July 1, 2025.

[116] 8 U.S.C. 1225(b)(1)(A)(iii)(II) (2025).

[117] 8 U.S.C. 1225(b)(1)(F) (2025).

[118] Brad Heath et al., “Exclusive: Thousands of agents diverted to Trump immigration crackdown,” Reuters, March 22, 2025.

[119] Shelby Bremer, “DEA special agent in charge of San Diego discusses immigration, US-Mexico border,” NBC7 San Diego, March 8, 2025.

[120] Ken Dilanian and Julia Ainsley, “FBI returning agents to counterterrorism work after diverting them to immigration,” NBC News, June 24, 2025.

[121] President Donald J. Trump, “Guaranteeing the States Protection Against Invasion,” January 20, 2025.

[122] Bill Hutchinson, “What we know about the foreign college students targeted for deportation,” ABC News, April 6, 2025.

[123] Gabe Kaminsky, Madeleine Rowley, and Maya Sulkin, “The ICE Detention of a Columbia Student is Just the Beginning,” The Free Press, March 10, 2025;

Michael Martin, Destinee Adams, “DHS official defends Mahmoud Khalil arrest, but offers few details on why it happened,” Morning Edition on NPR, March 13, 2025.

[124] Molly Farrar, “Tufts student detained by ICE releases statement while lawyers argue jurisdiction,” Boston.com, April 3, 2025; John Hudson, “No evidence linking Tufts student to antisemitism or terrorism, State Dept. office found,” Washington Post, April 13, 2025.

[125] President Donald J. Trump, “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship,” January 20, 2025.

[126] Nate Raymond, “Court hands Trump third appellate loss in birthright citizenship battle,” Reuters, March 11, 2025.

[127] Elizabeth Findell et al., “The White House Marching Orders That Sparked the L.A. Migrant Crackdown,” Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2025.

[128] Aaron Rupar (@atrupar), “Homan: "People need to understand ICE officers and Border Patrol don't need probable cause to walk up to somebody, briefly detain them, and question them ... based on their physical appearance,” X post, July 11, 2025.

[129] David J. Bier, “ICE Is Arresting 1,100 Percent More Noncriminals on the Streets Than in 2017,” Cato at Liberty (blog), June 24, 2025.

[130] Julia Ornedo, “Border Patrol Agents Brutally Detain Santa Ana Landscaper,” YahooNews.com, June 23, 2025.

[131] Republicans Against Trump (@RpsAgainstTrump), “ICE agents in tactical gear chase down and tackle a U.S. citizen in L.A…,” X post, June 21, 2025.

[132] “Order Granting Plaintiffs’ Ex Parte Applications For Temporary Restraining Order and Order to Show Cause Regarding Preliminary Injunction,” Case No. 2:25-cv-05605-MEMF-SP, July 11, 2025.

[133] “Order Granting Plaintiffs’ Motion for Provisional Class Certification and Granting Plaintiffs’ Motion for a Preliminary Injunction,” Case No. 1:25-cv-00246 JKLT CDB, April 29, 2025.

[134] “Order Granting Plaintiffs’ Ex Parte Applications For Temporary Restraining Order and Order to Show Cause Regarding Preliminary Injunction,” Case No. 2:25-cv-05605-MEMF-SP, July 11, 2025.

[135] Rachel Scully, “Noem on blocked ICE operations ruling: Judges are ‘getting too political’,” The Hill, July 13, 2025.

[136] Wong Wing v. United States, 163 U.S. 228 (1896); Jones v. Blanas, 393 F.3d 918 (9th Cir. 2004); Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678, 690 (2001); E. D. v. Sharkey, 928 F.3d 299, 306-07 (3d Cir. 2019)

[137] Julia Ainsley and Laura Strickler, “Trump's immigration enforcement record so far: High arrests, low deportations,” NBC News, July 10, 2025.

[138] Douglas MacMillan, “Immigrants forced to sleep on floors at overwhelmed ICE detention centers,” Washington Post, April 20, 2025.

[139] Marina Dunbar, “Two more ICE deaths put US on track for one of deadliest years in immigration detention,” The Guardian, June 30, 2025.

[140] Miriam Jordan and Jazmine Ulloa, “Concerns Grow Over Dire Conditions in Immigrant Detention,” New York Times, June 28, 2025.

[141] “Order Granting Plaintiffs’ Ex Parte Applications For Temporary Restraining Order and Order to Show Cause Regarding Preliminary Injunction,” Case No. 2:25-cv-05605-MEMF-SP, July 11, 2025.

[142] “Order Granting Plaintiffs’ Ex Parte Applications For Temporary Restraining Order and Order to Show Cause Regarding Preliminary Injunction,” Case No. 2:25-cv-05605-MEMF-SP, July 11, 2025.

[143] See Sec. 17: “Executive Order of January 20, 2025, Protecting the American People Against Invasion.”

[144] Joel Rose, “Justice Department sues Chicago and Illinois over ‘sanctuary’ laws,” NPR.org, February 6, 2025.

[145] “Sanctuary Jurisdiction Directives,” Office of the Attorney General, February 5, 2025;

Cities of Chelsea and Somerville v. Donald J. Trump et al, Case No. 25-10442 (Mass. Dist. Ct 2025)

[146] Rebecca Beitsch, “CIA director: ‘No assessment’ US at war with Venezuela amid use of Alien Enemies Act,” The Hill, March 26, 2025.

[147] Trump et al. v. J.G.G. et al., 604 U.S. ___ (2025).

[148] Verónic Egui Brito, “Despite refugee status in the U.S., young Venezuelan was deported to Salvadoran prison,” Miami Herald, March 21, 2025.

[149] Ilya Somin, “How Trump's Alien Enemies Act Deportations Violate the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment,” Reason, March 19, 2025.

[150] Verónica Egui Brito and Syra Ortiz Blanes, “Administration: ‘Many’ Venezuelans sent to El Salvador had no U.S. criminal record,” Miami Herald, March 19, 2025.

[151] Verónica Egui Brito and Syra Ortiz Blanes, “Administration: ‘Many’ Venezuelans sent to El Salvador had no U.S. criminal record,” Miami Herald, March 19, 2025.

[152] Ilya Somin, “How Trump's Alien Enemies Act Deportations Violate the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment,” Reason, March 19, 2025.

[153] Marc Caputo, “Exclusive: How the White House ignored a judge's order to turn back deportation flights,” Axios, March 16m 2025.

[154] Alison Durkee, “Judge Boasberg Thinks There’s ‘Fair Likelihood’ Trump Administration Violated Court Order With El Salvador Flights,” Forbes, April 3, 2025.

[155] Kyle Cheney, Hassan Ali Kanu, and Josh Gerstein, “Judge reaffirms order to return Maryland man erroneously deported to El Salvador,” Politico, April 6, 2025.

[156] David Nakamura, “Trump administration says it could take months to resume refugee admissions,” Washington Post, March 11, 2025.

Reading lots of words but it can be summed up with TDS.