The Best Books of 2024

70 Books Read. Recommendations for 2025

I set my first annual book target in 2015 and began recording every book I read from cover to cover, 722 in total. Here are my reflections on them for 2022 and 2023 and my recommendations for how to read many books well. I finished 70 books in 2024, four more than my goal of 66. The list below only includes books I finished. With a few exceptions, I won't mention the large number of books I skimmed or browsed. Below are the best books without negative reviews, which I’ve decided not to include. I generally didn't finish many bad books because life is too short, and I don't want to write negative reviews anymore unless I'm convinced there's a major positive externality to doing so. It’s better to forget bad books instead of negatively reviewing them.

Catherine Pakaluk’s Hannah's Children: The Women Quietly Defying the Birth Dearth was the best book of 2024. It blends an economic literature survey approach with a style that’s written for any audience but then has a large original qualitative section based on interviews of American college-educated women who intentionally had five or more children. What were their motivations? What did they think about having large families? Were they rich, poor, religious, rural, urban, come from large families, individualistic, communitarian, and more? Most modern books on fertility decisions are about why people have few children, so it was illuminating to read about mothers who decided to have many. These women are self-selected. They're religious and overwhelmingly conservative but have other personality traits that also push them to be more amendable to having larger families. It takes a streak of individualism to buck nationwide trends by having a large family that imposes high costs on parents, but it also seems to require a communitarian value set to increase the parent's benefits of having many children.

At a brown bag lunch at Cato, Catherine discussed other avenues for future research to expand on her book. Here are the additional research lines I’d like to read about. First, I’d like to read about why non-religious people choose to have larger families when they do. There aren’t many, which is one of the facts highlighted in her book, but there must be some, and I'd like to know about their motivations, which could become increasingly important to understand in a secularizing world. Second, it would have been great to read interviews of mothers who were Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, or from faiths other than Christianity or Judaism. The sample sizes for those other faiths are small, and many are recent immigrants mostly admitted for economic reasons, so they are less likely to have the other characteristics of mothers with large families. Still, there are some who are, like non-believers, more difficult to find. Third, an investigation into the fathers who want large families is missing. It's understandable to focus on the mothers because they have the most control over their own fertility, and the interviewers were women, so men may not be as candid with them, but one of the mothers that Catherine interviewed said her husband's desire for a large family was why she had as many children as she did. I want to know more about men like him. Most writings about fertility are mediocre. Hannah’s Children is a unique contribution worth your time and money.

The Conservative Mind by Russell Kirk is a brilliantly written history of conservative thought in the Anglo-American tradition. Kirk combines the uncommon traits of erudition with captivating prose. Intellectual histories are less interesting than they used to be because they mainly capture the opinions of a small subset of intelligent and thoughtful writers, not the modal understanding of the members of an ideological movement. Still, Kirk’s book is a good reminder that there is a deep reservoir of conservative thought that we should all remember in the age of MAGA. Conservatism isn't an ideology like socialism or libertarianism, but that doesn’t mean conservative intellectuals can’t be great thinkers.

What took me so long to read this classic? Decades ago, I read some of Kirk's essays and wasn't impressed by them. Youthful arrogance. Then, I reread his piece about libertarians and enjoyed it much, especially his prediction about libertarians fracturing and starting their own sects. He didn’t turn out to be specifically correct in the case of Murray Rothbard, but that general prediction does seem to hold over the lifecycle of many libertarian intellectuals. However, I'm unsure whether it holds more or less for libertarians than for adherents of other ideologies. It prompted me to give Kirk another try, and I'm glad I did.

Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany by Norman Ohler is different from other books you’ve read about the Nazis. If you’ve read dozens of books about World War II and the Nazis like I have, you’re probably thinking that there’s nothing completely new that you could read. Blitzed is a useful corrective to that arrogance. Nazi drug use, mostly of amphetamines, helped fuel the Wehrmacht, other branches of the armed services, factory workers, and the Nazi leadership – causing bursts of energy when the regime needed it, producing hangovers that were difficult to overcome in times of crisis, and turning Hitler into a hopeless addict by the end. The Nazi obsessions with goofy homeopathic cures like injecting pig hormones remind me of less sophisticated modern health fads. Overall, a well-written and darkly humorous book about a little-known side of the Nazis.

How the Allies Won the War by Phillips Payson O’Brien complements several recent histories of war production during World War II. O’Brien goes further by tying weapons production to strategy and explaining how they were complementary. Germany, Japan, the UK, and the US geared 65-80 percent of their war production to making and arming aircraft, naval vessels, and anti-aircraft equipment. Much of the production was to protect factories and supply lines – such as German and Japanese air defenses and Allied anti-submarine patrols. A large portion of the rest attacked enemy industrial and transportation sectors, such as the Allied bombing campaigns over Germany and Japan and the German U-boats, to halt or neutralize their weapons production. Unlike the other books about war production, O'Brien's descriptions of World War II remind me of video games where players gather resources, maximize production, and fight battles. The big lesson is that there's too much focus on decisive battles in modern history, which O'Brien claims didn't count for much when determining the war's final outcome.

I waited too long to read The Cult of the Presidency by Gene Healy. It’s indispensable in the age of strong presidents . . . or weak presidents with extraordinary powers. If you haven’t been radically skepticized against the presidency over the last 20 years, you haven’t been paying attention. Healy has been paying attention, and it shows. I recommend following Healy’s book with Why Not Parliamentarianism? by Tiago Ribeiro dos Santos. Healy makes several recommendations for putting the presidency back in a constitutional straight jacket, but there’s not much hope because the same political incentives that gave the presidency so much power would remain unchanged. Santos’ book provides a more radical reform proposal that would resolve the problem of independently powerful executive authority.

The best chapter of Santos' book is about how private corporations, which face far more intense and constant evolutionary pressure than governments, don't choose presidential governance systems. They're just different organizations after all, and private companies would choose the presidential system if they thought it would increase their profits. Instead, they go for a parliamentary form of organization with shareholders and boards who select the CEO and other officers. It’s not a perfect analog to parliamentary governments, but it's close enough. A dozen state governments should reform their constitutions to create parliamentary state governments to use America's federalist laboratory for democracy to try more radical changes in governance. One-party states would probably find such a reform most politically appealing. Santos' book is my only nonfiction reread (I first read it in 2021). That's how good it is.

The Achilles Trap by Steve Coll is about Saddam Hussein, American foreign policy, and decisions that led to both wars in Iraq. Coll is a learned and excellent writer who can bring all the characters alive and gives just enough back story for the casually interested consumer of foreign policy. I read Nuclear War by Annie Jacobsen during a one-day business trip to Pittsburgh. Maybe it's an alarmist book that exaggerates the harm of nuclear war, as odd as that sounds, but it still prompted me to spend a higher percentage of my family's budget on prepper gear.

Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony by Robert Edgerton is an antidote to the ubiquitous myth that primitive stateless societies are harmonious. It was imminently convincing on that front, but better because of its explanation of maladaptive cultural practices in many societies that are causing them to either trend toward extinction or assimilation. There are many behaviors that primitive people engage in that limit their material and reproductive success, but those behaviors persist for other reasons that are either inexplicable, benefit a small group of elites, based on commonly misunderstood causality, or lack of competitive pressure.

It can be hard to figure out which cultural practices are most maladaptive, although some sexual practices stand out. If there are five equally important cultural practices rated on a scale of –10 to +10 on adaptiveness, the average matters. In such a case, the society can thrive if some of those practices are negative or zero so long as the others are positive enough. But if some are negative enough to overwhelm the positives, society will shrink, stagnate, or begin to assimilate into more adaptive local societies. There’s room for improvement in any society, but it's hard to figure out how and what maintains cultural practices in the first place. Being stuck in a bad equilibrium is devastating for health, wealth, and reproduction. Firms compete and change rapidly due to market pressure, but the broader society doesn’t have the same adaptiveness. Is there a way to learn from firm behavior and shift social incentives to produce a more adaptive culture? Perhaps. This book is best read alongside A Concise History of World Population by Massimo Livi-Bacci, which is implicitly about successfully adaptive societies.

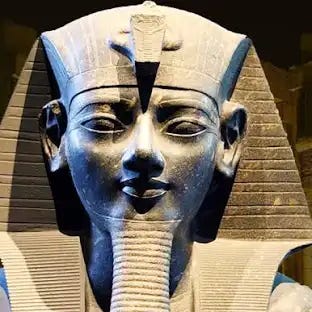

The First Great Powers: Babylon and Assyria by Arthur Cotterell cleared up many ambiguities I had about ancient history in the cradle of civilization. First, Babylonian, Assyrian, and Persian kings were not worshipped as gods like the Egyptian pharaohs. They ruled with the blessings and sanctions of their deities, but they themselves were not gods and were subordinate to the spiritual powers with a handful of tyrannical exceptions. Second, the Babylonian exile of Jews was a small proportion of the Ancient Hebrew population but a highly learned and influential group. Third, you did not want to be the foreign bride of Pharoah Amenhotep III as this passage explains:

Just how undistinguished foreign wives were in Egypt was evident when Amenhotep III could not confirm to the Kassite king that his sister was still alive. She had apparently sunk without trace among his other wives and concubines.

When Amenhotep III admitted that he had forgotten which of his wives Kadashman-enlil I’s sister might be, the Babylonian king sent envoys to talk to her. The scene at the Egyptian court had all the trappings of comic opera. As none of the envoys knew the Kassite princess personally, they were reduced to inspecting the pharaoh’s entire harem, the members of which were paraded before them in turn. The women refused to speak and so the envoys returned to Babylon none the wiser. Understandably, Kadashman-enlil I was not satisfied with this; but Amenhotep III blamed him for the confusion, saying that Kadashman-enlil I should have sent somebody who would actually recognize his sister on arrival at the court. Amenhotep III’s inability to identify his own wife as an individual, and his seeming lack of contrition over this, serves as proof of the limited power of foreign princesses in Egyptian courts.

This wasn’t a great year for fiction as I spent too much time on mediocre sci-fi with interesting premises, inept character development, and mediocre plotting – the typical problem with that genre. However, a few works of fiction stand out. The first two are Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World and Sputnik Sweetheart by Haruki Murakami. He's my favorite Japanese author, followed by Yukio Mishima. I read many of their novels in high school and college. Hard-Boiled was a reread from high school and has since held up as my favorite Murakami novel. Sputnik Sweetheart was merely good.

The Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee translated by Robert van Gulik is a collection of entertaining judicial procedurals set during the Tang Dynasty in China combined with a dose of Sherlock Holmes-style mysteries. At that time, magistrates served as judges, prosecutors, defense counsel, and investigators with police powers. The stories were written 1000 years after the fall of the Tang Dynasty, but they nonetheless give an interesting insight into Chinese society and the judicial system, much like The Golden Ass does for other aspects of Imperial Rome. Particularly interesting for law and economics aficionados as the incentives were odd, but Judge Dee was always honest.

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamin Labatut was a short novel about the lives, discoveries, and madness of Fritz Haber, Alexander Grothendieck, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, and others. You won't come away from this book knowing any more about physics because there’s no math, but you’ll come away with some more understanding of how tortured brilliance deals – or fails to deal – with difficult problems. The world goes by, it doesn't care, and all that is irrelevant to these brilliant minds. The book felt incomplete as if the author didn't finish it. Or maybe I just didn't want it to end.

Act of Oblivion by Robert Harris was about the global manhunt for the executioners of King Charles I. It prompted me to read The English Civil Wars: 1640-1660 by Blair Worden. The introduction of Worden's book is alone worth the price and time. I read Conclave by Robert Harris before I heard of the movie. The ending was absurd, so I haven’t seen the movie yet (no spoilers). Lest Darkness Fall by L. Sprague de Camp was the only good sci-fi book on my list. It's the novel for you if you've ever wondered what to do, as a modern man who spoke Latin, if you suddenly found yourself in Gothic Rome.

I started and didn’t finish Shogun by James Clavell and Darwin’s Dangerous Idea by Daniel Dennett. The former was fun, but I had enough after 500 pages. The latter was informative, but I understood Dennett’s point thoroughly without finishing. It was written for philosophers and historians of science, so you should check it out if either subject interests you. The opportunity cost of finishing them was just too great.

There’s one addition to my recommendations on how to read many books well: I usually take notes when reading them, but I decided to try that in the Excel file where I list my completed books. It’s a better way to record because a sentence of notes reminds me of other insights from the book, like a trigger for recollection, rather than having to pick up the book or skim my Kindle notes. Doing so has also filled me with some readers-PTSD and convinced me that I should have set down more books. I've wasted too much time on bad books and should be more ruthless like Tyler Cowen suggests.

My goal for 2025 is to read 60 books.

Complete books for 2024:

Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee

Anonymous Chinese Author

The City and the Stars

Arthur C. Clarke

Babylon

Paul Kriwaczek

The Conservative Futurist

James Pethokoukis

Slouching Toward Gemorrah

Robert Bork

The Last of the Wine

Mary Renault

No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention

Reed Hastings and Erin Meyer

A History of Writing

Steven Roger Fischer

Showdown at Gucci Gulch

Jeffrey H. Birnbaum

Bad Faith

Randall Balmer

The Conservative Mind

Russell Kirk

Real Education

Charles Murray

Facing Reality

Charles Murray

The Guest Lecture

Martin Riker

Judge Dee at Work

Robert Van Gulik

Human Diversity

Charles Murray

Lest Darkness Fall

L'Sprague De Camp

Blitzed

Normer Ohler

The Geek Way

Andrew McAfee

The Achilles Trap

Steve Coll

Hannah's Children

Catherine Pakaluk

The Two-Parent Privilege

Melissa Kearney

Domestic Extremist

Peachy Keenan

Thinking About Crime

James W. Wilson

Last and First Men

Olaf Stapledon

Act of Oblivion

Robert Harris

Conclave

Robert Harris

Co-Intelligence

Ethan Mollick

The Cost Disease

William Baumol

Cognitive Gadgets

Cecilia Heyes

The English Civil Wars

Blair Worden

Raven Rock

Garrett M. Graff

Ghost Wars

Steve Coll

What Went Wrong with Capitalism?

Ruchir Sharma

The Revelations

Erik Hoel

The Cult of the Presidency

Gene Healy

UFO: The Inside Story of the US Government's Search for Alien Life Here and Out There

Garrett M. Graff

Career and Family

Claudia Goldin

Sputnik Sweetheart

Haruki Murakami

Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World

Haruki Murakami

Why Not Parliamentarianism?

Tiago Ribeiro Dos Santos

Axiom's End

Lindsay Ellis

How States Think

John J. Mearsheimer and Sebastian Rosato

Genealogy of Morals

Friedrich Nietzsche

In Defense of the Corporation

Robert Hessen

Numbers Don't Lie

Vaclav Smil

The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It

David Bell

How the War Was Won: Air-Sea Power and Allied Victory in World War II

Phillips Payson O'Brien

The First Salute

Barbara Tuchman

Cadillac Desert

Marc Reisner

Day of the Assassins: A History of Political Murder

Michael Burleigh

The High Crusade

Poul Anderson

Tau Zero

Poul Anderson

The Twelve Caesars

Michael Grant

The Anatomy of Love

Helen Fisher

A Brief History of Intelligence

Max Bennett

The Prisoner in His Palace

Will Bardenwerper

Nuclear War

Annie Jacobsen

Norco80

Peter Houlahan

A Concise History of World Population

Massimo Livi-Bacci

Nine Lives

Aimen Dean

When We Cease to Understand the World

Benjamin Labatut

Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony

Robert Edgerton

The Culture of Fear

Barry Glassner

Wormhole

Keith Brooke and Eric Brown

The First Great Powers: Babylon and Assyria

Arthur Cotterell

Rise and Kill First

Ronen Bergman

The Quants

Scott Patterson

Terminal Boredom

Izumi Suzuki

Red Notice

Bill Browder

Great list! No Ukraine war books? I can recommend a couple if you're interested.

Five in and I’m definitely saving this. Some really interesting stuff here.