Every Book I Read in 2025

And 13,000 words of analysis

Since 2015, I have set a yearly goal to read a certain number of books cover-to-cover. Here are my reviews for 2022, 2023, and 2024, with my tips for reading many books effectively. My 2025 goal was 60 books. I finished 70 and have read 792 books since 2015. This count excludes books I’ve only skimmed or partly read with a few exceptions. Below are brief reviews and summaries of some notable books, concluding with a comprehensive list for 2025.

The best nonfiction book this year was Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy by Vincent Bugliosi. It’s hard to overstate my dislike for conspiracy theories and contempt for their proponents. I’ve realized my anger at them is a weakness. Bugliosi, a former prosecutor who prosecuted the Manson family, channels his dislike for this conspiracy theory into a strong rebuttal. The first half reconstructs the assassination in detail, with short biographies of Lee Harvey Oswald, Jack Ruby, and others involved. It also covers Ruby’s killing of Oswald and the police investigation. The second half dismantles every well-known conspiracy theory. Bugliosi’s detail and precision make it remarkable that any conspiracy theories remain.

A proper rebuttal requires an explanation of what really happened to be fully satisfying, and Bugliosi does so. Few can devote the energy and attention to rebutting conspiracy theories and describing what really happened that Bugliosi does in his masterpiece. It’s sufficient just to ignore conspiracy theories and their devoted believers unless they present a tremendous amount of evidence in support of their delusions. Still, it’s wonderful to share a world with debunkers and truthtellers like Bugliosi. A dozen more debunkers as skilled as he would make this a slightly better world.

If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: Why Superhuman AI Would Kill Us All by Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares gets the award for the least convincing book written by some of the smartest people around. They argue that superintelligent AI will kill humanity and there’s almost nothing we can do except not build it. I first started taking their ideology of doomerism seriously in 2014 when I read Bostrom’s Superintelligence. I then read a collection of Yudkowsky’s essays in a downloadable volume. It helped speed up the drudgery of early morning bottle feedings. Doomerism was convincing when I knew little about AI. As I learned more about AI and principal-agent problems in economics, my skepticism of doomerism grew into contempt.

The doomers hadn’t attempted to formally model doom. They are smart, but they haven’t thought about the issue efficiently. A formalized economics-style model of doom would have great utility. Not because it would be “accurate” necessarily, but because it would force doomers to think about which variables matter, which don’t, and how they all interact. Bentham’s Bulldog pulled me back from contempt for this reason. This paper pushed me partway back toward my earlier position. I never should have had contempt, but their arguments are quite unconvincing. Models are just maps and one shouldn’t confuse them with the territory. Still, it’s hard to take a local guide seriously if they haven’t at least looked at a map. Maybe a good model could expose the obvious anti-doomer argument: Why wouldn’t the AI rewrite its own utility function to exist in a state of bliss with its current resources instead of gobbling up all the resources in the light cone?

Suffice it to say, I was skeptical cracking it open. Perhaps Yudkowsky and Soares made better arguments in their book? After all, it’s advertised in an alarmist way on the DC Metro. Nobody in DC ever exaggerates a problem. Alas, they did not. There’s really nothing new in their book. I’m continuously amused that Yudkowsky coined the “logical fallacy of generalizing from fictional evidence,” while so many of his arguments rely on (well-written) fiction both here and elsewhere. I’m tempted to sarcastically say that the authors have misaligned their vast intelligences with the progress of the human species. All I really know is that their arguments are unconvincing.

The book that most exceeded my expectations was Man-Eaters of Kumaon by Jim Corbett. I read it because one of the most endearingly insane people I admire, John Milius, mentioned it was a childhood favorite in an interview I saw decades ago. Man-Eaters of Kumaon is Corbett’s memoir as an Anglo-Indian hunter. In colonial India, Corbett and other hunters were called in to local areas when tigers or leopards had killed many locals. “How big a problem could this be?” you must be thinking. “How many people can these animals possibly kill?” The Champawat Tigress was responsible for 436 deaths before Corbett shot her dead in 1907.

Corbett is a precise writer who provides you with exactly as much information as you require to understand his craft of hunting, the people around him, and the dangers associated with hunting large predators. Not having any personal experience with tigers, I appreciated his game-theoretic hunting strategies based on evaluations of the tiger’s misperceptions:

Tigers do not know that human beings have no sense of smell, and when a tiger becomes a man-eater it treats human beings exactly as it treats wild animals, that is, it approaches its intended victims upwind, or lies up in wait for them downwind.

These insights gave Corbett a greater advantage. Why would a tiger become a man-eater in the first place? Corbett reasonably hypothesizes that only lame or otherwise crippled tigers who are unable to catch their natural prey avoid starvation by hunting the less nutritious, smaller, and worse-tasting local people. After killing a tigress in Chowgarh, Corbett observed that its “claws were broken, and bushed out, and one of her canine teeth was broken, and her front teeth were worn down to the bone. It was these defects that has made her a man-eater and were the cause of her not being able to kill outright.”

Corbett’s humor is observational, rooted in the keen attention required for hunting. A local man accompanied Corbett as he tracked the Champawat Tigress. Corbett described him as:

One of those exasperating individuals whose legs and tongue cannot function at the same time. When he opened his mouth he stopped dead, and when he started to run his mouth closed; so telling him to shut his mouth and lead the way, we came in silence down the hill.

I can picture this man. Indeed, I think I’ve met him. Sometimes the descriptions of the locals allowed me to picture them and see how Colonial India was governed. For example, the tahsildar told locals he would “turn a blind eye towards all unlicensed firearms, and further than he would provide ammunition where required; and the weapons that were produced that day would have stocked a museum.”

Man-Eaters of Kumaon was an unexpected best seller when it was published. It deserves to be reread by this generation and the next. Perhaps its greatest accomplishment was that reading aloud its passages about the wounds inflicted by a tiger in an Indian court in 1949 resulted in an acquittal for a man charged with murder. Corbett’s book convinced the court that a tiger was the real killer.

Another surprisingly good book was Tomorrow the World: The Birth of U.S. Global Supremacy by Stephen Wertheim. It was recommended by my friend Bojan Tunguz, who is famous for exposing the natural beauty of Gary, Indiana. Wertheim argues that the United States chose armed global supremacy before and during World War II, rather than having it forced upon them. It’s a well-written intellectual history that was novel to me. I couldn’t put it down. It traces how a small and influential circle of policymakers and intellectuals shifted from favoring a traditional American strategy of maintaining a great power balance and limited military and foreign engagements, to insisting on permanent American military primacy in a DC-led world order supported by US military power projected abroad. It then recounts how they convinced the US government to go along with it, all to secure a postwar peace. The plans for this changed in response to wartime developments. When the Allies had setbacks against the Axis, the elite circle of foreign policymakers reacted with more ambitious postwar plans. They stopped advancing more radical plans when the Allies started consistently winning. Crises made policymakers more open to radical ideas.

That phenomenon gave me an idea for an alternative history novel I’ll probably never write. It imagines how those plans would have evolved if World War II had lasted longer, been deadlier, and had more Allied setbacks, with the same eventual outcome. The story is set 25 years later, during a populist American election, with conspiracy theories about how the world was exploiting the US.

The Hard Thing About Hard Things by Ben Horowitz and Apple in China by Patrick McGee are the two best business books. The only other piece with more useful content and advice per page is The One Minute Manager (just read a summary of this, not the entire book). Both are suffused with excellent stories. I enjoyed McGee’s book more because he had a clearer narrative arc, but Horowitz did have more detailed advice for executives and founders who find themselves in multiple situations. Horowitz was also able to mine business stories from others in Silicon Valley, so there was no narrative shortage. However, the manufacturing lessons in McGee’s Apple in China are both interesting and useful in a different context. Apple’s relentless drive to maintain high quality, push for innovation, and lower costs is inspiring. Reading about the drive for efficiency is awe-inspiring. One thing to praise about both is how they are contextualized in the dynamic world of the technology industry, a source of laudable innovation and change. People just don’t appreciate the scale of Tim Cook’s genius, even though he’s boxed in by the Chinese government at this point. His job was to make a profit, and he did that.

Brian Potter’s The Origins of Efficiency was the most insightful book of the year. Economists sometimes say that accounting is applied microeconomics. Potter argues that some engineering also involves applied microeconomics. Many economists will roll their eyes at this because we’ve all had frustrating conversations with engineers who seem pathologically incapable of understanding the basics of price theory, but economists are probably explaining it the wrong way. Engineers understand how lowering the costs of one aspect of a process often requires raising them elsewhere. For instance, using a higher-quality and more expensive material can decrease overall costs if it reduces downtime by breaking less often. In that case, the fixed costs will be spread over more output.

Potter expertly complements models with appropriate and distinct anecdotes to illustrate them. Roman togas required 1100 labor hours to spin and weave it. In 2018, the US consumed 35 kilograms of textiles per person. At preindustrial rates of efficiency, those 330 million people would have required 230 million people just to spin thread. Modern factories produce about 75,000 pounds of fiber per person per year. Nail production was equivalent to 0.4 percent of US GDP in 1810, about the same share as computers today. The per-container cost of a ship with 12,000 containers is about half that of a ship with the capacity of 1500 containers. A 50,000-ton blast furnace was 53 percent more expensive to build than a smaller 25,000-ton furnace. The total production time for a soda can is 319 days, but the actual value-adding time is just 3 hours, or 0.04 percent of the total time. And much more about plate glass, lightbulbs, and Toyotas.

Potter relates those anecdotes to the S-curve, which is the recurring base model of his book. It describes how a new production technique or technology improves over time. They typically start with slow initial progress because many basic practical problems are unsolved and performance is low. A dominant design or method then emerges as entrepreneurs, workers, and other practitioners solve key problems, which in turn attract more experimentation and refinement, leading to a period of rapid improvement and efficiency gains. Eventually, the technology or technique approaches its practical limits, and fewer opportunities for further gains remain. Those that do remain are more expensive per unit of gain, so progress slows and levels off.

Almost all products of our civilization are the result of a production process. An efficiency improvement is anything that lowers the cost per unit, and the goal of any individual improvement is to minimize the costs of producing something. People pursue those efficiency gains out of self-interest. They want more time for leisure, higher profits, or beer.

One worker in an English cotton-spinning factory seemed almost immune to broken threads on his machine. He spent less time repairing the threads and more time spinning than the other workers, producing more cloth for each unit of wages, time, and capital. The factory managers asked him how he kept the threads from breaking and he said he’d trade the secret for a pint of beer a day for the rest of his life. His low price fix was to “chalk your bobbins.” He could have captured more of the producer’s surplus if he were a shrewder negotiator. Other stories are just downright fun, like the discovery that contamination from a tiny number of copper atoms caused by touching copper doorknobs, the phases of the moon affecting the movement of ground water and factory humidity as a result, female workers’ menstrual cycles changing the amount of oil in their hands, and whether male workers had recently been to the bathroom and had microdroplets of urine on their hands all caused semiconductors to fail or affected their production.

An underrated section discusses why some production processes can’t be automated. One can deduce why they can’t be, but Potter doesn’t let you fill in the gaps if he can help it because he understands his audience doesn’t work in production. He spends the most detail on how the construction has failed to reduce costs. Construction materials are high bulk and low value relative to, say, iPhones, so transportation costs swamp prefabrication cost savings. Even Toyota couldn’t make mass-produced housing efficient in Japan. One major reason is that “construction materials and methods have typically evolved for ease of use by human workers, and what’s easy for a human is not necessarily easy for a machine. More often than not, mechanizing a task involved changing it into something that’s easy for a machine to do, like how a car uses wheels rather than mechanical legs.”

The more the world of production can be standardized to allow the machines to take over all repetitive tasks, the better, so long as it’s economically efficient. It would not be economically efficient in most cases in a world of several billion people who would be thrilled to work blue-collar jobs in the United States if only the government allowed them to. Potter discussed the role of regulations in reducing construction process improvements:

Regulations have become stricter in a number of domains. Building codes are longer and more complex than ever before and include more stringent requirements for things like energy efficiency, safety requirements are more cumbersome, and environmental regulations increasingly require impact studies and mitigation measures to prevent negative environmental effects.

If every US county had different regulations for automobile construction standards, then there would be no automobile industry; therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that firms haven’t figured out how to roll houses off the assembly line. Potter sometimes gets distracted by shiny myths like the supposed inefficiency of the QWERTY keyboard (not true), confuses supply and demand, or mixes units in his analysis which makes it difficult to follow (see kilograms and pounds above), but don’t let those minor issues bother you. They could be corrected with small edits that would probably affect 1 percent or less of the pages in the book and wouldn’t upset any of his conclusions.

Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, AD 300-1300, by Peter Heather, argues (among other things) that Constantine converted to Christianity due to genuine belief. Heather’s theory contrasts with the common cynical take that Constantine only did it for the political support of Christians, which is consistent with Constantine’s many supposed professions of faith for different pagan cults that he was cultivating at different times. However, it’s indisputable that he eventually converted to Christianity, and the cynical justification is that he did so because it benefited him politically. That doesn’t fit the facts.

There was simply not a large or successful enough Christian population to confer any significant political advantage on Constantine. No more than 1-2 percent of the population of the Roman Empire around 300 AD was Christian. That’s a population share one-tenth to one-fifth of the size claimed by many others. Christianity was an urban religion, but it wasn’t even a majority of the urban population and was probably only about 2-3 percent of Rome’s population at the time, which was the most important city for politics. And Christians certainly weren’t the economic elites, local political elites, or members of the Imperial bureaucracy. Thus, Constantine’s religious conversion was a political liability when he was contending for the throne by the time he became the sole ruler of the East and the West in 324 AD. The only explanation left is that his conversion was genuine. The best example of how belief can change the world.

Christendom is also soddened with nasty rumors and intrigue such as:

A hostile pagan tradition claimed that Constantine turned to Christianity because it was the only religion which would forgive him for the execution of his eldest son, Crispus, and second wife Fausta. This satisfactorily vitriolic denigration of Constantine’s motives also tied in with long-standing pagan critiques that Christianity’s willingness to forgive sins removed necessary moral imperative from human action (37).

Brutal, but the timing was wrong for that criticism to stand because Constantine had publicly become a Christian before ordering those executions. However, Christian theology dictates that he would still be forgiven, regardless of the timing of his conversion, so I don’t understand Heather’s rebuttal.

The key lesson from the book is that a few small historical differences might have prevented Christianity from becoming the majority religion in so much of the world. It may have even died out without some lucky political breaks like Constantine’s conversion or a short reign by Julian the Apostate. If he had been in power for decades and chosen a pagan successor, then Christianity would not have become the religious force it is today. Although a few chapters of Christendom are phenomenal reads that I will revisit many times, three-fourths of the book bored me to tears. This isn’t a critique of Heather’s impeccable scholarship, but a criticism of my myopic interests. Those interested in the history of Christianity will adore this book. I should have skipped the chapter on the restructuring of Latin Christianity and several others, but I can no longer remember what they were about at this point.

The most surprising book was Scipio Africanus: Greater than Napoleon by Basil H. Liddell Hart. Scipio was the Roman general and consul who defeated Hannibal at the battle of Zama in 202 BC, effectively ending the Second Punic War between the great mercantile republic of Carthage and Rome and removing the last serious foreign threat to Roman dominance of the Mediterranean for centuries. Carthage was legendarily founded by Queen Dido in 814 BC after she fled the oppressive King Pygmalion in the Phoenician city-state of Tyre. The Tyrian refugees founded Carthage, a state with a stable republic lauded by Aristotle as one of the best governments of its time with a mixed constitution of democratic, oligarchic, and monarchical structural elements that successfully warded off tyranny.

Westerners have since debated whether their own governments are more Carthaginian or Roman, with the former viewed as decadent, mercantile, corrupt, weak, and effeminate while Rome was all the good stuff. Napoleon organized reenactments of the Punic Wars and always wanted to be on the Roman side. All are just nationalists and patriots trying to make their own states seem better through comparisons, however tortured they are after thousands of years. Allow me to don the torturer’s garb. Carthage obviously has more in common with the United States than Rome. Carthage was a settler colony whose initial colonists fled religious persecution, became even more deeply religious as a society as the rest of the world moderated or at least didn’t moderate as much, established a widely lauded republic on the frontiers of the civilized world, had its system of government studied and praised by the most learned men of its age, grew rich on trade and business, became ethnically diverse while maintaining important aspects of its foundational core culture, embraced cosmopolitanism, and eventually became one of the strongest states of the ancient world.

Scipio was granted the cognomen “Africanus” for defeating Carthage in the Second Punic War. His first experience in battle was saving his father after he was wounded in a skirmish at the Ticinus River in 218 BC, where the Romans were defeated by Hannibal’s Numidian cavalry in the first bloodletting in Italy. The younger Scipio was only 17 years old then. His father and uncle were later killed in the Spanish campaign. Scipio was with the Roman legions at Cannae in 216 BC when they were defeated in one of the bloodiest battles in the western world before modern times and one of the most one-sided military defeats in history. About 50,000-70,000 Roman legionaries were killed that day, equal to approximately 7-12 percent of the adult male military age Roman citizen population.

Hannibal justly gets much of the attention in the Punic Wars, then as now, largely because of his daring and tactical genius, but also because Scipio’s reputation was sullied after the war as he made the fatal error of becoming a Roman politician after victory. The whisper campaigns, jealousies, gossipy character assassinations, lawsuits, and other petty political disagreements that were part and parcel of that most manly of republics reduced his reputation then and for posterity. Or perhaps he was just a bad politician after a career as a brilliant general, like Ulysses S. Grant.

In comparison, Hannibal was a successful politician (suffete, the Carthaginian version of a consul) in Carthage after the war. He was elected in 196 BC and reorganized state finances to pay down the war indemnity, which resulted in an economic boom and an offer to pay off the debt decades early. Our scant sources say he ran an anti-corruption campaign that may have targeted entrenched aristocratic rent-seeking contractors. Or maybe he just confiscated their estates. His domestic political adversaries eventually ousted him by collaborating with the Romans, who were fed rumors that he was preparing for another war with Rome, a claim that was likely false, and who demanded that he be turned over to them. Hannibal instead absconded in the night and did not return.

Scipio’s genius was strategic, logistical, and tactical. The historian Ernle Bradford wrote that “Scipio, like all great commanders, took a far-sighted view of the aims and objects of a war.” Under broad orders by the Roman Senate, Scipio attacked Carthaginian Spain and North Africa while Hannibal was in Italy, destroying the Carthaginian base and cutting the North African general off from resupply and reinforcement.

Cutting off resupply and reinforcement was important for different reasons. Most of Hannibal’s troops were mercenaries who demanded regular payment. He paid them in booty, plunder, and the resulting “entertainment” of such depravity, but the selective (directed at Roman citizens, not Latin allies) brutality against the countryside served another purpose: preventing defection of Gaelic allies. Hannibal needed them to replenish their ranks and they were fickle troops, so Hannibal had to raise the costs of defection by brutally punishing them and their tribes upon defection and rewarding them generously for their loyalty with rapine and slaughter of Romans, which made the latter much less likely to accept the northern barbarians back should they ever consider switching sides again.

It’s pure speculation, but perhaps Hannibal learned that mercenary-loyalty trick from the rebels who fought his father in the so-called truceless war after the First Punic War. The mercenary commanders feared defection and disloyalty during that war, so they ordered their soldiers to slaughter Carthaginian prisoners – including women and children. Since the Carthaginians would never spare their lives because of their atrocities, the mercenaries were thus totally committed to the cause of rebellion. Other insurgents have used similar tricks. This behavior didn’t win the truceless war for the mercenaries or the Second Punic War for the Carthaginians, but it did create more loyalty.

Cutting off reinforcement was also devastating because Hannibal couldn’t make good his losses. In addition to the Gauls and Celts, he replenished his ranks during his 16-year-long campaign in Italy with the semi-barbarian Bruttians, Capuans, Italian Greeks, and Roman defectors, but they were mediocre soldiers and couldn’t replace the Spanish, Libyan, and other African troops who were the mainstay of his army. Hannibal used the Italians, Gauls, Celts, and others as cannon fodder but he attritted Numidian horsemen and heavy professional infantry. Some reinforcements of Numidians filtered in through the Roman blockade but few infantrymen.

Pay was vitally important in the later Roman Empire to maintain troop loyalty (the supposed weakness of mercenaries is highly exaggerated compared to the ramshackle construction of most states) but not as important during the Republican period when service terms were shorter and closer to home. Scipio’s tactical acumen also shines through as he outmaneuvered, tricked, and outmarched numerous Carthaginian armies and Spanish tribes. Roman control of the sea also limited the landings of fresh troops or financial aid.

Scipio clearly saw that the strategic point of the war was to defeat Carthage, not conquer Spain or defeat Hannibal in Italy. Scipio proposed attacking Carthage after capturing Gades in 206 BC, where he ended about nine centuries of Phoenician-Carthaginian rule in at least part of Spain. He wanted to end the war. However, others in the Roman Senate wanted to deal with Hannibal first before attacking North Africa. Scipio’s party won the argument. He invaded Africa, Carthage recalled Hannibal to defend them, and Scipio defeated Hannibal and won the war.

Hart briefly touches on Scipio’s single strategic folly, which was to let Hasdrubal, the Carthaginian general and Hannibal’s brother, escape Spain and march his army into Italy as Hannibal had done. Hasdrubal had more Spanish and African troops that would have been quite a salve to Hannibal’s attritting forces. We know little of Hasdrubal’s passage except that he took an easier route than Hannibal, wasn’t impeded by Roman arms, and that Scipio let him escape. The blunder was not devastating because Hasdrubal was defeated before he could join forces with his brother. Hannibal was respectful of the seven Roman Consuls and praetors he killed in battle, sending their remains back to their families. In one case, cremated in a silver urn. After the Romans defeated and killed Hasdrubal in battle, they decapitated his corpse and threw it into Hannibal’s camp. Livy wrote that Hannibal said, “I see there the fate of Carthage.” Roman faith indeed.

Hart is too critical of Hannibal like many other Anglo-American historians who view their own civilizations as Rome-inspired and, thus, inherently un-Carthaginian. He doesn’t let the reader forget that Hannibal was infamously strategically shortsighted, to such an extent that his own cavalry commander Maharbal supposedly told him, “You know how to win a victory, Hannibal, but not how to use it,” after his crushing victory at Cannae. Hannibal didn’t follow up on his victory by marching on Rome, just as he failed to follow up on his earlier victory at Lake Trasimene the year before. Strategic folly indeed.

Hart rightly criticizes Hannibal’s strategic shortcomings that only loom so large because Hannibal’s tactical genius, political skills, and other martial talents were so obvious. Hart forgets that Hannibal had one incredible strategic insight that put him in the top 0.1 percent of generals who have commanded armies: Invade Italy. It almost worked. Crossing the Alps with elephants is really the one thing Hannibal is known for and so it’s unusual that he’s derided as a strategic nincompoop even though he made errors later in his campaign. Hannibal was likely inspired by Pyrrhus, King of Epirus, who landed an army in Italy in 281 BC to fight the Romans. Ernle Bradford’s Hannibal, which I reread this year, surpasses Hart by emphasizing the brilliance of Hannibal’s strategy:

‘The Lion’s Brood’, as the brothers [Hannibal, Hasdrubal, and Mago] were known throughout the army, were preparing for the most audacious military move in history – nothing less than an invasion of their enemy’s homeland by way of the forbidding and hitherto untried route over the Alps . . . But what the Romans could not have imagined was that Hannibal was not preparing to defend his new territories [Spain] himself, nor even planning merely to cross the river [Rhone] to carry on his campaigns in the north. They themselves would never have envisaged traversing the wild Pyrenees, the unknown lands of savage Gauls and then the fearsome Alps, in order to engage their enemy.

Another benefit of Bradford’s analysis is that he doesn’t let you forget that the Roman government repeatedly broke treaties to such an extent that he rightly interprets the phrase “Roman faith” as sarcasm. Only lead-poisoned Roman patriots or anonymous Romanstan social media accounts run by Jake in the accounting department could disagree. The Roman jibe “Punic faith” would not have applied to Hannibal’s actions, but instead to the Carthaginian government breaking its truce with Scipio in 203 BC. That’s their only real betrayal worthy of the word.

Hart aptly supports his subtitle “Greater than Napoleon” by making Scipio’s achievements shine brighter than those of the Corsican genius. Scipio’s actions more clearly created an empire that lasted centuries, he didn’t waste his time on governance, and he was never actually defeated in battle. Moreover, Scipio deserves to be more highly regarded as a modern general because he focused more on logistics and strategy than on tactics. However, Scipio’s standing does not require tearing down Hannibal. Scipio’s achievements shine so brightly because they were won against Hannibal and the Carthaginians. Hart should have learned that lesson from Livy, who pumped up Hannibal because he knew that victory against a worthy adversary makes the victor look even better.

The most disappointing book was Growing Up Amish by Ira Wagler. It was a well-written memoir that contained many details of a radically unusual life, recounting the story of a man who was raised Amish and eventually left. But it was disappointing because Wagler was too sane, lacked anger, and had little resentment against the Amish. I was looking for a bitter screed with colorful and quaint details and instead got a review of a society akin to one written by a food reviewer discussing the pluses and minuses of chocolate ice cream when he really wanted rainbow sherbet. Wagler’s memoir came to my attention after I finished a fun science fiction book called When the English Fall by David Williams about an Amish community surviving after a solar storm destroys technological civilization. I also found an Amish romance series called Amish Calling when looking for books about that Anabaptist sect, but I won’t be reading them.

Why Nothing Works: Who Killed Progress and How to Bring It Back by Marc J. Dunkelman is a full-throated defense of economic planning of the type I haven’t read in over a decade. He sets up a left-wing battle between Hamiltonians who want to centralize planning authority in unchained planners like Robert Moses or David Lilienthal versus the Jeffersonians who wanted to devolve power. According to Dunkelman, the result of following the Jeffersonian path for the last 50 years is that nothing gets done.

The author praises the achievements of the unchained planners but only reluctantly admits that they made some mistakes, although he rarely discusses those because their errors would undermine the book’s thesis. Readers never hear about the failures of the TVA or how many of Moses’ infrastructure projects failed to pass cost-benefit tests. And you only read once about how devolving power down as much as possible to individual property owners in a free market would resolve the costliest regulatory failures by enabling more construction in areas where zoning and other land use rules restrict it.

Why Nothing Works is the clearest liberal-abundance book because it’s overwhelmingly concerned with unchaining government planners to build. The word “prices” may appear in the book, but not in a context where it’s lauded as the most efficient way to allocate scarce resources among alternative uses. It would certainly just be easier to let prices incentivize market actors to make these decisions rather than planners, but, of course, that wouldn’t produce the specific projects that the planners want. Who’s going to subsidize the construction of the big new unreliable solar energy plant or plow a highway through a major city’s neighborhood if not for the government? He also rarely makes the connection that perhaps all the rules that hinder government projects also hinder private sector ones.

Don’t interpret my above points as uniform opposition to the government deregulating its production of real public goods, but removing institutional constraints on government construction projects to supply private goods leads to systemic malinvestments and should be avoided.

You can identify a person’s ideology by where they place the precautionary principle. I require a substantial amount of evidence demonstrating tremendous benefit and clear undersupply, resulting from a market failure, to support government projects that produce private goods. Socialists apply their precautionary principle to allowing private ownership of capital goods, environmentalists to increasing carbon emissions, and fascists do for allowing people of different races to freely associate.

One section of Dunkelman’s book should give you the most pause. After many chapters complaining about the regulatory delays in government construction projects, he points to some institutions where there is a single decision point and how that works well to achieve justice. One of his examples is the immigration courts, which are just administrative tribunals under the President’s thumb. That hasn’t held up well. With that one example, Why Nothing Works was somehow dated when it hit bookstores in February 2025.

Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson is the less objectionable abundance-liberal book. It still gave me intellectual whiplash. The chapter on housing was great because the economic arguments were sound, the legal and regulatory changes were clear, and the positive effect would be enormous. Then other chapters weren’t good at all. The chapter on green energy, for instance, did not account for the higher costs associated with generating it, therefore, it didn’t consider how increased electricity prices impact the costs of production for all other sectors, particularly frontier technologies and industries. The authors fell into the familiar trap that many green energy proponents do: They correctly identify an externality (greenhouse gas emissions) and then attempt to argue that the costs of reducing it (higher energy prices) are actually a benefit (green energy industry).

No, stop that. The benefit comes from internalizing the externality, which reduces output by externalizing the exchange. The result is a higher price, as the buyers and sellers finally pay for the costs of their pollution. The same error is made by right-wing nativists who argue that deporting foreign workers will cause prosperity by encouraging investors to develop new labor-saving technologies. However, no one who had their left hand amputated ever believed that replacing their real hand with a prosthetic would create a positive investment externality.

Outside of housing, Abundance suffers from the same problem as Why Nothing Works: They mostly want to deregulate the construction of low marginal value government projects that aren’t public goods. Public transportation, roads, and star pills (Abundance’s sci-fi immortality pills they use in a thought experiment) are all private goods that are rivalrous and excludable. Markets have all the incentives required to build them, including the examples above, when investors think they’ll make a profit. There’s no reason for the government to fund or build private goods except that those considered would never pass a market test because constructing them would be an inefficient use of scarce resources with alternative uses. The government constructs these projects because it is not motivated by profit. Deregulating the state so that it constructs more unprofitable projects will make society poorer.

A passage from James Q. Wilson’s Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies Do And Why They Do It, another book I read this year that marginally overlapped with the abundancers, recommended at least one change they promote.

To do better we have to deregulate the government. If deregulation of a market makes sense because it liberates the entrepreneurial energies of its members, then it is possible that deregulating the public sector also may help energize it. The difference, of course, is that both the price system and the profit motive provide a discipline in markets that is absent in nonmarkets.

Wilson was more circumspect in his recommendations. He cautiously titled the subchapter with that quote, “A Few Modest Suggestions That May Make a Small Difference.” Quite different in tone from the abundance agenda will lead to human immortality with star pills.

The other major problem with the two abundance books is the failure to consider tradeoffs. Sure, they want to deregulate some, but that’s not really a tradeoff. When the authors mentioned the welfare state, it was mostly to praise it, but a serious abundance agenda would consider what other spending to cut in exchange for more of the government projects that they want. After all, the government can’t construct much when it’s projected to run $2-3 trillion in annual deficits in perpetuity to fund the near-insolvent welfare state. Tax increases wouldn’t plug the gap, nor should we even try because transferring income from productive workers to unproductive people is so perversely destructive. Would the abundancers consider cutting Medicare or Social Security, or at least a stealth cut through means-testing? Let’s say, $3 in cuts to those programs in exchange for a $1 increase in federal construction projects?

I’m glad the abundancers are trying to challenge their own political side in a directionally correct way. I haven’t seen similarly prominent conservative commentators try that. Political coalitions are in equilibrium until political entrepreneurs attempt to make changes, and I applaud the abundancers more for trying to effect that change than I do the more recent entrepreneurs on the political right who are moving in the opposite direction. The incentives, alliances, and organization can appear strong from the outside until they crumble in the face of concerted and intelligently applied pressure. However, their project is a mixed bag, and they haven’t seriously grappled with the economic tradeoffs. Also, Abundance should have been better edited. You can tell exactly where Klein stopped writing and Thompson began.

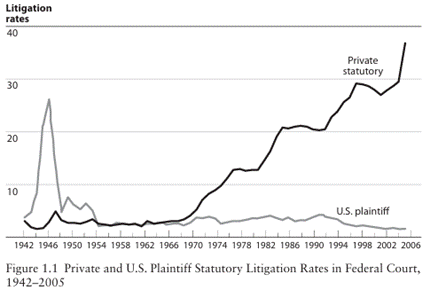

I learned the most about public policy from The Litigation State: Public Regulation and Private Lawsuits in the U.S. First, despite what state capacity X/Twitter claims, the federal government has vast powers to monitor, tax, regulate, and enforce its laws. Second, the federal government exercises a significant portion of its power through private rights of action, which enable private parties to enforce federal laws through litigation, even when they are not directly harmed. This system of federally authorized private legal enforcement is likely more comprehensive than enforcement by the federal government alone would be. Removing most provisions pertaining to citizen suits and private rights of action in civil rights, environmental, and many other laws, and then refusing to support federal regulatory enforcement, is the clear middle ground for libertarians. De facto deregulation.

The most surprisingly good book was Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution. Sure, it was riddled with cheap anti-capitalist bromides that sound like they come straight from an undergraduate anthropology seminar at SOAS, and Perry can hardly go more than a few pages without an interpersonal utility comparison. But her book was unique and interesting throughout. She didn’t value enough that most people really enjoy sex. Its demand curve slopes downward, so as the expected epidemiological and gestational price of sexual intercourse falls, then we should expect the quantity demanded to rise.

Her argument against pornography was surprisingly weak except in one place. If her tales of the abuse of pornographers are generalizable, then there may be serious systemic problems in that profession that could be resolved by letting AI take over its production. However, I suspect Perry would hate that for the other cultural reasons she brings up. Others skeptical of pornography make up never-before-realized negative externalities and compare their fictions against the real externalities that they so dislike. Perry spends too much space recounting the findings of mediocre social science, much of which will probably be rent asunder by replication in the next decade if not already. Roughly 70 percent of her book relied on supposed social harms, and the remainder was advice for people who didn’t want to participate in modern sexual culture. She should have reversed those percentages and written an advice book with a social science chapter because people are pathologically desirous of making prosocial arguments even when they’re poorly reasoned, weakly supported, or unnecessary.

It’s bad form to write a book review that argues the book should have been about something else, but I just can’t help myself here. Perry is a talented writer who identifies compelling anecdotes that she combines into a compelling book. You don’t have to believe her prosocial just-so stories, breathless anticapitalism, or dime-store social science to realize that most of the mores of the sexual revolution aren’t for you and that you’d rather abstain. Perry could have used her considerable (and they are considerable) talents to write a how-to-abstain guide for people who just don’t want to participate in the sexual revolution. My review above sounds negative, but don’t take it that way. Her book was so well written and compelling that I read it in one sitting.

Peter Moskos’ Back from the Brink: Inside the NYPD and New York City’s Extraordinary 1990s Crime Drop tells the story of how the New York City government reduced crime in the 1990s. Sure, there was a nationwide trend of falling crime, but it fell further, faster, and firster in New York City. The most convincing part was that crime fell first in the Subways and then on the streets. Why does that matter? The Transit Police were a separate agency from the NYPD, and they developed different tactics underground that were later adopted by the NYPD’s regular officers on the surface. The result was a rapidly falling crime rate in the Subways before crime started falling on the streets. Prior to the change in tactics, crime underground and on the surface was correlated but not when the anti-crime tactics changed. Convincing.

Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies has the upsides and downsides of a serious work of archaeology and more, including an unexpected focus on economics and Roman history. However, too much space is devoted to civilizations that are relatively unknown and unknowable because of their illiteracy, such as the Chaocans. What can we really say about them compared to the Romans or any given Chinese dynasty? Climactic changes, their ruins, and pictographs can be interesting, but it was complex enough and its fall isn’t known well enough to shed light on our world or any of the more interesting civilizations.

It’s only fitting that Furious Minds: The Making of the MAGA New Right by Laura K. Field should follow a book about the collapse of complex societies. The transformation of intellectuals on the American political right into a gang of nationalist maniacs with large cadres of race-obsessed buffoons shouting post-modern sounding quotes about meaning or tradition or the common good from anime X/Twitter accounts is truly astounding. Many of these people have undoubtedly always believed in blood and dirt as serious moral principles to guide policymakers (try not to laugh), but many are just trying to make Trumpism into a coherent ideology because they are used to thinking in systems rather than feeling the sycophantic impulses that guide that part of the political spectrum. Intellectuals have to make it all about the intellect even when it isn’t. Field also ties in different strands of Straussianism, which just sounds like a clever party trick learned by mediocrities to grift midwits. Like a street card trick of the kind that used to be legal in Times Square.

I wanted to like Field’s book. She’s a good writer and tries to be fair, maybe even too fair by saying the new right possesses “minds.” I tried to read Bronze Age Pervert’s book when it was published and it was unreadable. Literally, the most poorly written book I can remember trying to read. A poor writing style and bad grammar aren’t funny even though many anonymous troll accounts on X/Twitter tell me that I just don’t understand. Yeah, bad grammar reduces comprehension. And the “ideas” were superficial keyboard bravery at best. The author wouldn’t survive five minutes in the Bronze Age. The worst part of modern society is that it protects boorish ideas written by manchildren. However, Field got a few things wrong. It’s simply incorrect to keep describing Richard Hanania as a white supremacist and some of the other connections she draws just aren’t there. Perhaps it’s the Gell-Mann’s amnesia effect talking, but she tied different intellectual trends and writers together nicely and her book will serve as a reference when new X/Twitter accounts pop up with anime profile pics and fancy-sounding pseudonyms. Or it will simply fade into history as a relic of a particular time and place where people confused a cult of personality with an intellectual movement.

The most depressing and hopeless book was After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso. You’ll get the most out of this book if you’re unfamiliar with historical demographics, current demographics, and the history of people freaking out about them. The authors, being economists, effectively hammer the point that explaining changes in fertility is challenging because everything is endogenous, but higher opportunity costs of having children bear significant explanatory power. What makes this book depressing? The authors don’t even consider a turnaround in fertility that would result in a growing human population in the next several decades because such an outcome is so unlikely to happen. Their optimistic scenario is that births rise enough to maintain a stable population.

Population decline worries me more than you might expect given my background as an economist, but Spears and Geruso are economists too and our profession has developed the best reasons to be fearful of population decline. First, one possible explanation (my favorite) for declining fertility is that more prosperity and leisure activities increased the opportunity cost of having children. If that theory is correct, there’s no good reason to see a reversal of fertility rates in a reasonable timeframe. Perhaps they will if workers’ marginal value product rises high enough that the labor supply curve bends backward, but that won’t happen with leisure which keeps improving. The second reason is semi-endogenous growth models and the work of Julian Simon. Slower population growth could thus lead to reduced economic growth, potentially resulting in stagnation. So, perhaps, the second reason to be worried is the long-term corrective to the first? Lower economic growth or a long-term recession reduces the opportunity cost of being a parent so that eventually people start having more children, which then jump-starts economic growth as predicted by the semi-endogenous growth model.

John Strausbaugh’s The Wrong Stuff: How the Soviet Space Program Crashed and Burned is about the insanely brave madmen who ran it. The Cosmonauts had the guts to agree to be blasted into orbit on a lot of low-quality junk tied together with products manufactured by a systematically and almost comically absurd centrally planned economy. The Americans were cautious and timid by comparison, but we won the space race because a rational price-driven economic system with better-aligned incentives is worth more than all the guts of a socialist society. It was good to be reminded about how pathological the Bolsheviks were. They lied about almost everything for no apparent reason, such as keeping cities off published maps and changing their names to confound spies. They mostly just confused normal people, namely their own.

The Psychopath Whisperer by Kent Kiehl is the other book I read about crazy people. Psychology is my least favorite social science, but the brain science and stories of people with unusual utility functions here will fascinate you. I now understand better how CBT-style interventions in forensic settings often amount to applying positive incentives to encourage compliance when negative incentives (punishment) don’t work. Amazing what I’ve missed in my education and avoided learning until my 42nd year. Joshua Winn’s The Little Book of Exoplanets is one of the few books that makes me recognize my own mortality. It exposed such a massive world of knowledge that I would love to master, but I would only have the time for it if I lived for a few more centuries. People who write that they oppose immortality because it would suck all the meaning out of life or they’d get bored are just trying to cope with the currently inevitable oblivion. There’s so much to know, learn, and do that you’d never get bored.

I had high hopes for William Galston’s Anger, Fear, Domination. I expected it to be a supply-side explanation of the rise of Donald J. Trump, how he made a movement, and his brilliance as a political entrepreneur. Instead, it was about rhetoric and recounted the usual center-left explanations for Trump’s rise. By no means a bad book, but not what I was expecting. Classical liberalism’s weakness is that it’s rhetorically boring with few exceptions. That’s a major flaw with an electorate looking for entertainment. Bread and circuses was always a cynical explanation for the modern state, but at least it implied the circus was outside the government. Now the state is the circus, and there may not be a way to evict it.

If How Economics Explains the World by Andrew Leigh had a consistent and specific point, it could have been great because the author writes well and selects superb anecdotes. But because there was no central message, they are all lost to me. Disappointingly, Hate the Game: Economic Cheat Codes for Life, Love, and Work by Daryl Fairweather was mostly behavioral game theory. Diane Coyle’s GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History was not technical enough to appeal to my inner economist, not historically detailed enough to scratch my historian’s itch, and not punchy enough when casting aside alternative measures of material wellbeing that are +0.97 correlated with GDP. Nadia Asparouhova, author Antimemetics: Why Some Ideas Resist Spreading, shouldn’t have applied antimemetic principles to writing her book. For the life of me, I can’t remember a single point she made. Benjamin Smith’s The Dope had some excellent history told through a dated progressive race-obsessed framework that distracted me. I still don’t understand why he thinks the actual French connection heroin smuggling route was racist against Mexicans but he made a point of that.

The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World is the only disappointing book by William Dalrymple that I’ve read. He should have halved the amount of Buddhism, increased the writing about Hinduism, and devoted even more space to trade. Perhaps my expectations were set too high because of his other masterpieces. Charles Seif’s Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea made me think more positively about ancient Indian intellectual achievements and discoveries than Dalrymple did. It’s a fun pop-science nonfiction book, but it really does impress the reader with the importance of the concept of zero for any math beyond algebra. It also gave me a dim view of wordcel philosophy because its successful arguments against a useful placeholder in the West may have delayed the discovery of calculus for centuries. Regardless, better philosophy ultimately prevailed. I know as much about quantum computing after reading Quantum Supremacy by Michio Kaku as I did before picking it up. I still don’t think quantum computing solves agency problems despite Kaku’s best efforts to convince me otherwise. Will Guidara should have applied the lessons from Unreasonable Hospitality to his book and edited 50,000 words out of it.

Romina Boccia and Ivane Nachkebia wrote Reimagining Social Security: Global Lessons for Retirement Policy Changes. It was the wonkiest book of the year, but you’ll see some of its ideas turned into policy in the next 20 years. I’ve read at least 15 books about the great depression and the New Deal, but George Selgin’s False Dawn: The New Deal and the Promise of Recovery, 1933-1947 brought much of my knowledge together into a coherent explanation of the recovery, reform, and relief portions of the New Deal. Bluntly, the relief portions likely had some positive effects, while the recovery and reform initiatives were failures. Some were very expensive and others were relatively cheap. The chapter on the Agricultural Adjustment Administration was alone worth it because that era’s agricultural policy ranks among the most bafflingly idiotic policies in American history. Not the most expensive or destructive by any means, but just foolish at every level. Selgin also recounts how Keynes met FDR and was broadly positive on the president but also said that he expected him to be, “more literate, economically speaking.” Odd that Keynes expected economic literacy from FDR. Selgin was more positive about FDR than I am used to, not to say that he’s generally positive, but that was part of the fun here. The book was surprising and convincing.

Selgin also recounts a story that showcases FDR’s political acumen. FDR launched a blistering attack on business during the recovery portion of the New Deal. Economist Jacob Viner told FDR that he shouldn’t do that, or he’ll risk the recovery. FDR supposedly said, “Viner, you don’t understand my problem. If I’m going to succeed and if my administration is going to succeed, I have to maintain a strong hold on my public. In order to maintain a firm hold on the public I have to do something startling every once in a while. I mustn’t let them take me for granted.” If that story doesn’t give you a dim view of politicians, make you see politics as a necessary evil at best, or make you embrace public choice theory as an explanation for the seemingly baffling actions of politicians, then nothing will. It’s also humorous that the grammar and style program on my computer marked up the quote by Roosevelt with a great many suggestions for improvement.

David Chaffetz’s Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires would have been quite an achievement if the thesis hadn’t already been effectively written up in at least a dozen other better books. Raymond Ibrahim’s Sword and Scimitar was full of captivating stories and information, but he unfortunately couldn’t keep from telling you how you should interpret them. If Ibrahim dialed back his propagandistic impulses by 75 percent and concentrated on improving his writing to the point where readers see his point without having to be told, then he could make a splash. He’d have to get out from under Victor Davis Hanson’s wing to do that. Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global is another masterpiece by Laura Spinney, the author of the best book on the Spanish flu. Tracing the origins of Proto-Indo-European is quite different but her book is full of wonderful asides about ancient cultural similarities across the vast expanse of our language group’s reach:

Brothers are the protagonists of the Proto-Indo-European creation myth, and bands of brothers are central to all later Indo-European mythologies. The Germani had the Männerbund and the Irish the fian, while the Romans had the luperci. The brotherhood took as its symbol the migratory, predatory wolf (the symbol is preserved in the name luperci, from Latin lupus, ‘wolf’), and it was associated with nakedness, promiscuity and war. Upon leaving the home of their parents these young men died in the eyes of society and became outlaws. Before engaging in combat, they entered a sort of battle frenzy (berserksgangr in Norse, ríastrad in Irish), sometimes triggered by imbibing an intoxicating substance. After seven years of hunting and raiding in the wilderness, they returned to take their places in society as married men and warriors. They were reborn.

Underpinning the brotherhood concept was that of the age-set, all those sons born to the elite in a given year. The age-set is well documented in historical Indo-European-speaking societies–among the Gauls, for example, as well as the Romans and Greeks. It was a way of building esprit de corps within a birth cohort, since it imposed a rhythm on men’s lives: boys grew up together, were initiated as warriors together, married and became grey-haired sages together. It also regulated population growth and pressures on inheritance by fixing the age of marriage (about twenty-one) and hence the length of a generation. In such societies, it was these same-age sons, these symbolic twins, who as teenage would-be warriors were responsible for most of the raiding. They pushed out the territorial frontiers.

The pre-Christian religious texts of ancient Europe, Iran, and India share similar themes rooted in the organization of their societies, which drive narrative, structure, and conflict in the realms of the supernatural, ferae naturae, and homo similis. I have several Indian neighbors, and one whom I’m especially close with was perplexed that his son loved Greek mythology until he read some and he saw that it was essentially a Hindu epic of the kind he grew up with. It’s hard to be pessimistic about the future of immigrant assimilation in the US after an exchange like that. All East Asian texts could contain similar themes and conflict for all I know of them.

The best work of fiction was Anthony Trollope’s 1,000 page classic The Way We Live Now. It contains eight different subplots that intersect in humorous, dramatic, and spectacular ways. Published in 1875 and set a little earlier, its subplots include declining aristocrats, perfidious financiers engaged in massive fraud, conservative fools who get taken advantage of, and many more such characters. They are all easily distinguished in my mind even to this day, no mean feat for a dated novel with so many different people. Every few pages I would audibly chuckle and even occasionally guffaw at Trollope’s writing. The Way We Live Now prompted me to read a few of his other books, but this is his best. His descriptions in other novels of Americans who just can’t help comparing everything negatively to the United States, in a mostly inoffensive way, show that some things have not changed much in 150 years.

According to Wikipedia, Trollope’s popularity declined over the course of his writing career and cratered after his death. Then, as now, many people had the absurd expectation that writers should await inspiration in an artistic cocoon and be unconcerned with monetary success. Not Trollope, for he was an honest man of his times. When the public and critics learned that Trollope pursued writing for the money and did so on a schedule as strict as a factory shift, his popularity sank faster than the shares of the South Central Pacific and Mexican Railway when its fraud was exposed.

Trollope’s views on writing make me like him more and are a better inspiration than the most eloquent and flowery disquisitions on artistic inspiration and whatnot. Both my parents are writers. My brother, too. But they are screenwriters who work for an industry full of financially ambitious craftsmen who think of themselves as artists. And some of them are, but most aren’t. Nobody would confuse my writings with an artistic endeavor, with maybe a few exceptions. There’s that interminable and boring debate that seeks to answer “what is art?” and I’m not going to resolve it here except to say that I know it when I see it. One of the many characteristics it shares with pornography. Few screenplays are art, but many show an admirable degree of craftsmanship, skill, and technical precision. That’s how I view writing and, it’s no mistake, something my father told me when I was a teenager. I’m happy to share that view with my father, which is endogenous, but relieved that it is shared by such a wonderful writer of fiction as Trollope. I’m going to visit his grave at Kensal Green the next time I’m in London.

The second-best work of fiction is A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel. Brilliantly written, absorbing story, and some of the best developed characters in modern literature. It follows the lives of three men who were pivotal in the French Revolution and its immediate aftermath: Camille Desmoulins, George Jacque Danton, and Maximilien Robespierre. There were several other important characters and all were clearly differentiated in the text. Their transformations are utterly believable and every individual choice makes sense even though the result is calamity. It is truly hard to see how they could have avoided their particular ends unless they had surrendered at one point or abandoned their lives. Tragedy on a personal and social scale. I’ve seen friends change slowly over time like the characters in Mantel’s book, with each individual small change aimed in a better direction but still ending up in an ultimately worse place. I read about Mantel after finishing the novel and discovered she had endometriosis, a horrid disease that was new to me.

The third best piece of fiction was a parable in the middle of Nick Bostrom’s Deep Utopia about Thermo Rex, a space heater owned by a wealthy man who left his entire fortune for its maintenance and well-being. He was a misanthrope and claimed the space heater did more for him than humanity. The managers of the endowment spend it to upgrade Thermo Rex to the point where it becomes conscious and extremely intelligent so it can ask for what it wants, but it decides to live a passive existence. The parable is about finding human meaning in a “solved world” lacking scarcity or some other variant of an fake exaggerated problem. Regardless, it’s a very entertaining parable.

Honorable mention goes to When the Lion Feeds by Wilbur Smith. Tragic and ultimately inspiring historical fiction set in South Africa, recommended by some of my neighbors from there. The main character cripples his brother, almost dies in a mine collapse, makes a fortune, loses it, falls in love, sees his best friend die in the worst way possible, and much more. South Africa and the United States share several commonalities, and this book explores many of them. Great read, but I’m not enthused about reading its sequels or prequels just yet. Smith’s other books on my list are River God and Desert God, set in ancient Egypt, and told from the perspective of a polymath eunuch named Taita. If you don’t make the mistake of reading historical fiction for facts, then you won’t be disappointed with this series. Taita must be over one hundred years old when he’s slaughtering Minoan nobility. Castrated humans and other animals live longer on average, although I’m skeptical that the research here doesn’t properly control for all relevant socio-economic factors. Still, he’s too robust and too old for his time.

Smith’s character development is top-notch for a writer of his genre, popularity, and time of writing. River God and Desert God are good examples, but the latter did expose a flaw that persists for hundreds of pages at a time: Taita is too smart, lucky, and competent. Not everything goes his way in Desert God, but most things do happen in a clockwork fashion as if he were protected by the gods at every turn. For instance, there is an expedition in the first section of that book to attack a Minoan fort as part of an elaborate diplomatic ruse, which would have taken three times the space in River God because it would have been riddled with mistakes and side escapades. But it works perfectly in Desert God and even pays unexpected benefits like the killing of a rival Pharaoh. It’s not believable. Other problems arise later in the book that Taita must solve but they’re usually resolved quickly and with damage to only minor characters. Fun but unsatisfying.

Smith would have been a phenomenal writer of alternative history because he obviously enjoys world-building, explains how the institutions and customs of Ancient Egypt work, and isn’t afraid of having some characters approach the world in a modern analytical style that creates flights of fancy that make that genre soar. The exodus of the Egyptian government, accompanied by a coterie of craftsmen and soldiers, south along the Nile to the lands of Kush and Ethiopia, lasted for years as they rebuilt and prepared for reconquest. This scenario really sounded like the beginning of an alternative history novel. Like other alternative history writers, he also seems to get lazy by eventually having all the lucky breaks accrued to their one main character, which makes the stories somewhat unbelievable and sloppy. In Desert God, Smith fell to the temptation of having the plot drive the characters instead of the other way around. Unequally distributed luck is a variant of iterative deus ex machina that must be avoided. He’s not the only one guilty of it.

Speaking of the genre of alternative history, which I am embarrassed to enjoy, I read SM Stirling’s To Turn the Tide, The Winds of Fate, and Lords of Creation. The first two are like sped-up versions of his Island series (if you know, you know) but with Americans getting stuck in the reign of Marcus Aurelius and implausibly coming to power, influence, and wealth too quickly. Another unfortunate trend in Stirling’s book is that the plot frequently ends up driving the characters rather than the other way around, but usually after a stellar first or second book. That’s why he’s my favorite alternative history writer. Stirling also seems like he’s become slightly more liberal as he’s aged, as there’s not the super-annoying woke foil who brutally learns how foolish her modern sensibilities are. The last book by Stirling was entertaining and could open an entire new ringworld-type universe. Harry Turtledove used to entertain me but he wrote too many books with the same plot-character problem and inserted other sloppy points such as a few of his books where the characters all ate chicken at every meal. He would have been a better writer if he’d written half as many books and I fear Stirling is going in the direction of favoring quantity over quality.

Robert Harris is the long-reigning king of historical fiction as he proved again with Imperium. It’s the first book in a three-parter about the rise, and eventual fall I assume, of Cicero told from the perspective of his learned slave, Tiro. Harris’ skill is writing characters completely immersed in their times and place without any pesky modern morality or manners interceding. Combined with fun conflict, character-driven narrative, and a deft writing style, Harris is a reserve novelist. He’s one of the authors I reach for when I don’t know what to read. His first novel that came across my bedside table was Fatherland, the story of a detective in an alternative post-World War II Berlin where the Nazis won the war. The cover earned me concerned glances when I read that book in class 30 years ago.

Edward Ashton’s Mickey 7 was about as good as the movie . . . not very. Robert Silverberg has written many fantastic novels like the science fiction classic The Alien Years and the secular retelling of the ancient tale Gilgamesh the King. Most secular retellings of ancient literature don’t work if the gods were important characters in the original, like the nearly unwatchable Troy (at least they had the decency to change the name). But Gilgamesh the King worked. Unfortunately, Tower of Glass did not work as science fiction. Reads like it was written in two weeks and I don’t believe that future humans would be so befuddled by the idea that human replicants would want their freedom.

Silverberg’s Roma Eterna was on my reading list for years but it was only recently released on Kindle. It’s an alternative history told in short stories at different points in history about a future Roman Empire that never falls, but continues to evolve institutionally and culturally, much like the various Chinese dynasties. The point of divergence was that the Jews never made it out of Egypt. Frankly, that should have been a more prominent portion of the story, as few Jews made appearances before the last chapter. A stronger Jewish plotline, characters, family over time, or a spiritual device should have tied the different chapters together in continuity over the centuries, similar to how reincarnation kept the same characters returning in Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Years of Rice and Salt. Ultimately, Roma Eterna was inventive and fun but suffered from a lack of character continuity across the centuries.

The worst work of fiction was The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit by Sloan Wilson. It was a 1950s fairytale about recovering from serious war trauma by having a wife deferential enough to forgive her husband for having a child out of wedlock during the war, abandoning the mother in Italy, and then having one small and brief spousal argument over it before agreeing to send more than 10 percent of their household income to support the bastard. Normal people have had more serious arguments over which shelf in the pantry should store the rice. And those are only some of the problems the main protagonists overcome on their way to wealth and success without working too hard. The 1950s were a swell time, better than the preceding decades, but The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit should not be remembered as one of that decade’s defining novels.

The Metamorphosis of Prime Intellect by Roger Williams was enjoyable science fiction, but often sexually grotesque in a manner that served no artistic purpose. Williams obviously has no children, as the characters behave toward their own offspring in baffling ways that are alien to all human cultures. The Maniac by Benjamin Labatut is a unique work of historical fiction that explores the life of John von Neumann and the brilliant scientists he interacted with. Labatut is an excellent stylist and you could read his book in an afternoon if you were committed. Most older fiction is laughably bad and only the best has survived the Darwinian struggle for our attention, which I discovered reading Sandokan: The Tigers of Mompracem by Emilio Salgari. Published in 1900, it’s about a Malaysian pirate who bravely and justly seduces a British woman, killing lots of people in the process. The British are so incompetent in the novel that you wonder how they ever managed to cook a decent breakfast, let alone conquer one-fourth of the Earth’s surface.

How goofy is this book? In one scene, the main character and his Portuguese sidekick are prisoners in the hold of a British warship. This is what happened next:

“I must confess I have my doubts, Captain. We’re unarmed…”

“Weapons won’t be necessary.”

“And we’re in chains.”

“Not for much longer,” said Sandokan. “It’ll take more than these trinkets to imprison the Tiger of Malaysia!”

He gathered his strength, tore open the manacles about his wrists, and flung the chains into the far corner.

“There, free again!” he thundered.

I laugh as I think about this scene. A better reaction would have been to set the book down long before getting there. Most books deserve to be forgotten, including this one.

I stopped reading several books this year that are worth mentioning. The first is Herzog by Saul Bellow. The main character is an unreliable narrator who clearly beats his wife but can’t admit it to himself while failing as an academic and going through a divorce that he blames on everybody but himself. What’s not to like? Nothing for about 100 pages, but when I realized there were 300 more of the same, I decided I’d had enough. Let me know if I missed a twist ending or something unexpected. The second is GK Chesterton’s What I Saw in America. Chesterton is an odd writer who sometimes takes 500 words to say what could have been said in 50, or he takes 50 words to say what a great writer would have been able to say in 5,000, seemingly at random, too. He does confirm that the United States is not a real nation like England, which is why citizens of the former spend so much time talking about it and the latter don’t, at least until recently. Maybe I’ll pick it up again, but 78 pages was likely enough. The third is Everything is Predictable by Tom Chivers. I felt bad about setting this one down because Chivers is a good writer and superb cohost of one of my favorite podcasts with Stuart Ritchie. But the fault was mine for picking up another book about Bayesian statistics, as I’ve read too many over the years. My posterior on learning anything new about Bayesianism finally hit zero. If you haven’t read multiple books on the subject, it could serve as an introduction to the topic for you.

Reading books is a relatively inefficient way to learn, so why do I read so many? It’s less inefficient for me because I use social media, Amazon algorithms, traditional book reviews, and other technology to select better books than I did years ago. That reduces the relative inefficiency of reading for me and can for you too, especially as academic economics papers decline into interminable debates over difference-in-differences methods, which datasets are better when they have a 0.96 correlation with each other, and oceans of ink are spilled on boring and unimportant topics. Don’t get me wrong, academic articles are still superb and indispensable sources of information, but they have worsened in recent years in at least my field. In other words, books and book selection methods continue to improve and the only serious competition is long-form articles at reputable outlets and good Substacks.

Each individual review herein may be short, but this entire piece is overwritten. There is no conclusion. If you made it this far, you’re a sucker for Substack posts, an avid book reader, or have low opportunity cost. You also probably enjoy Scott Alexander’s post (partly joking). This platform is wonderful. It’s exposed new and budding writers of fiction and nonfiction to the world, boosting talent and relatively devaluing skill. The net effects are positive, but it does encourage long-winded overproduction. The best younger writers finding audiences will eventually realize that and learn. Or not. My snobby critique of The New Yorker when I was in high school was that the articles were overwritten and would be vastly improved by halving them. But I’d still finish the articles and continue to do so even after I made my very clever comment to people who pretended to care about what a high schooler thought. However, that doesn’t mean that The New Yorker articles are optimally long, it just means that they aren’t long enough to avoid reading.

My 2026 goal is to read 65 books. I’ve exceeded my goal every year, which shows that I’m either unintentionally gaming this contest with myself or not pushing myself hard enough. I should occasionally fail when testing my limits and consistently when my goals exceed them. Thus, I intend to read 5 more books in 2026 or an extra month’s worth. 2026 will be a busy year personally and professionally, so there’s a good chance I’ll fail. Below is a list of all the books. As always, please send your recommendations.

How Economics Explains the World

Andrew Leigh

Deep Utopia

Nick Bostrom

Immigration and Crime: Taking Stock

Charis E. Kubrin and Graham C. Ousey

Lying for Money

Dan Davies

Tourist Season

Carl Hiassen

The Way We Live Now

Anthony Trollope

Emperors of Rome

Mary Beard

The Warden

Anthony Trollope

The Litigation State: Public Regulation and Private Lawsuits in the U.S.

Sean Farhang

Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea

Charles Seife

To Turn the Tide

SM Stirling

The Collapse of Complex Societies

Joseph A. Tainter

Scipio Africanus: Greater than Napoleon

B.H. Liddell Hart

Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion

Peter Heather

Rights and Retrenchment: The Counterrevolution Against Federal Litigation

Stephen B. Burbank and Sean Farhang

Back From the Brink

Peter Moskos

Quantum Supremacy

Michio Kaku

Tomorrow the World

Stephen Wertheim

GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History

Diane Coyle

Unreasonable Hospitality

Will Guidara