Immigration and Housing: An Epic Win-Win

Guest response to Nowrasteh's piece on how immigrants affect housing prices

The following is a guest post by my friend Nathan Smith responding to a piece I wrote last year. If you want to publish a post here about immigration then pitch it to me and I’ll consider running it.

Late in 2024, Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute, who is generally an advocate of immigration, published an article in which he conceded an important point to the other side: “it is safe to say that immigrants increase housing prices in the United States.”

Well, not exactly.

It is to Nowrasteh’s credit that, after applying some basic economic reasoning and looking at a variety of studies, and having been led to the conclusion that immigration, on balance, mildly raises housing prices, he states it frankly. Nowrasteh is honest. A less scrupulous immigration advocate wouldn’t have given such ammunition to the other side. While higher housing prices raise the net worth of incumbent homeowners, many native born citizens stand to lose if housing becomes less affordable. So higher housing prices supply a strong argument against immigration.

But increased immigration will not make housing less affordable. Nowrasteh’s concession was a mistake. It’s not completely false. Logically, the statement that “immigrants increase housing prices in the United States” seems to qualify as true if just two or more house prices in the United States rise as a result of increased immigration. That would happen, of course. It’s likely the case that the average house price would be higher with increased immigration, all else equal. But the average house price isn’t really relevant because no one pays that. Moving past the logical and semantic hair-splitting, we can say that:

Major policy change in the direction of increased immigration would alter the set of houses for sale and the mix of prices at which they would sell.

The patterns in those changes are somewhat predictable.

There are cogent descriptions of those patterns.

“Immigration raises some housing prices” is one of those true cogent descriptions of one of those foreseeable patterns.

But “immigrants increase housing prices in the United States,” without the qualifier “some,” is not a cogent description of an actual pattern that occurs when policy becomes more open to immigration.

If policy liberalizes, increased immigration will foreseeably affect housing prices in two main ways. First, it will grow cities, and raise the value of real estate in urban cores by increasing the amenities of density to which that real estate provides access. Call that the “urbanization effect.” Second, it will reduce housing prices at the margin, by supplying low-cost labor with which to build houses. Call that the “low-cost labor effect.” With respect to the average housing price, the two effects go in opposite directions. The urbanization effect pushes up. The low-cost labor effect pushes down. The effects might average out to a nationwide increase, or a nationwide decrease, but which way the average price shifts doesn’t impact the effect on human welfare.

For welfare, both the effects are positive. Increased immigration causes incumbent homeowners to enjoy capital gains because of the urbanization effect and also provides aspiring homebuyers with similar houses with similar amenities more cheaply because of the low-cost labor effect. Win-win. That’s the takeaway.

Where does Nowrasteh go wrong? Economic reasoning generally requires a mix of data and theory, and Nowrasteh’s article is no exception. But he picks the wrong theoretical exercise as a lens for interpreting the data. There’s a better way to model the impact of immigration on housing, and it yields a more nuanced and more unambiguously optimistic result.

Demand, Supply, and Housing Prices

Figure 1 shows the mental model behind Nowrasteh’s conclusion that “immigration raises housing prices.” There is a demand curve and a supply curve for housing. Demand slopes down, supply slopes up. The price and the quantity sold occur at the intersection of demand and supply.

In his article, Alex Nowrasteh doesn’t draw the classic graph, but he expresses the same thing in words:

The intersection of supply and demand determines housing prices, like all prices. When housing supply curves are upward-sloping, increased demand from immigrants will increase housing prices. Immigrants are people who want roofs over their heads, after all. Housing supply is relatively inelastic in many places, in part due to government policies like zoning and height restrictions … but the housing supply will not become perfectly elastic even if all land use laws are abolished. That means that higher demand, all things equal, will drive up prices as well as the quantity of housing.

Immigrants also induce a housing supply effect because 10 percent of all foreign-born workers labor in the construction industry, which rises to 14.9 percent for noncitizens, according to the 2023 American Community Survey… However, all immigrants demand housing. Even immigrants who work in construction increase housing demand first before they can construct more housing. That increase in demand drives up prices and incentivizes new supply through further construction, renovation, or increasing the supply of rental units through other means. However, the marginal immigrant increases housing demand more than he increases housing supply.

Nowrasteh’s argument tracks the naive Econ 101 approach to housing markets, as shown in Figure 1, very closely. Housing prices are determined by demand and supply, immigration increases both, but demand more, so housing prices rise.

To see the error, note that the underlying model assumes the “law of one price.” It features one housing price. The law of one price is a general feature of all Econ 101-type models. It’s almost always a bit of an over-simplification, but it’s often roughly applicable. Not in housing. The chart below shows the price distribution of house sales in the last quarter of 2025:

How can a model of housing markets that assumes one house price be applicable to a real world where the top 15 percent of houses sell at well more than double the price of the bottom 15 percent of houses? The reality is that housing isn’t one market but many overlapping markets. Some changes, like a rise in interest rates, will more or less affect all housing markets in similar ways. But not immigration.

Of the various ways the housing market is segmented, the most important for present purposes is the difference between sales of existing houses and the construction of new houses. Those two supply curves are not alike, at all. So the best way to model immigration’s effect on housing consists of two charts: one chart to model the market for existing housing; another chart to model the market for new housing.

But the reason to bifurcate the housing market model doesn’t just have to do with the inaccuracy of the “one price” assumption. Figure 1 is tolerably accurate as a loose summary of many local or regional housing markets, but it confuses the welfare economics. The biggest reason to make a better theory is that we want to know who benefits from the housing market changes that will occur with increased immigration.

The Welfare Economics of Housing Markets

What we really care about in the workings of markets is not prices, but welfare. Does change make people better off? And remarkably, the simple Econ 101 graph can shed much light on that.

When you draw supply and demand curves, you don’t just tell a causal story about how prices are determined. The area under the demand curve is significant, too. It signifies total willingness to pay for any given quantity sold. The metric represented by area in the chart turns out to be dollars, since a price times a quantity is a number of dollars. Dollars, in turn, are so useful that they can be treated as a measure of welfare. So when we show how markets change due to shifts in demand and supply, we can see what happens to the areas between curves, and interpret the changes as the impact on the welfare of different groups. “Consumer surplus” is the name given to the increase in welfare enjoyed by buyers as a result of the existence of a market. “Producer surplus” is the name given to the increase in welfare enjoyed by sellers.

Figure 3 shows a welfare analysis of a change in housing markets similar to what’s shown in Figure 1, but with labeled regions to help explicate the impacts on welfare.

The labeled regions show quantities of welfare impacted by housing markets. In the scenario shown in Figure 3, an increase in immigration causes demand to shift from D to D’, and supply to shift from S to S’. Pre-increase, the price of housing is P*, the quantity is Q*, consumer surplus is C+B, and producer surplus is A. Post-increase, the producer surplus is A+B+F+G, and consumer surplus is C+E. Region B is lost as consumer surplus and gained as producer surplus due to the rise in price. Producers also gain region F due to higher prices and region G due to expansion of supply. Consumers gain region E due to increased demand. Total surplus rises by E+F+G as the housing market grows.

The gain in total surplus is good, and consistent with economists’ long-standing advocacy of generous immigration policies as a way to make the economy more productive, and to generate net benefits for a lot of people. But if you’re worried about natives in particular, those gains in total surplus are not very reassuring, because you’ll be worried that all the benefits might be going to immigrants. And Figure 3 doesn’t provide any breakdown for that.

Crucially, the rightward shift of the demand curve doesn’t come only from immigrants. The urbanization effect will also increase the use-value of housing and urban cores to incumbent homeowners, and some of the increased housing demand will come from urban homeowners who enjoyed capital gains and are leveraging that to buy bigger homes in cheaper areas.

In terms of natives versus immigrants, the one thing that is clear is that incumbent homeowners and landlords, who are overwhelmingly natives or immigrants who were already residents before the policy change, will enjoy gains of B+F as the houses they own appreciate in value. Area B is transferred to incumbent homeowners from buyers, but who are the buyers– natives, or immigrants? A mix. If we want to shed light on the welfare impacts on natives versus immigrants, we need a different model.

By the way, the concept of consumer surplus is a bit unfashionable because modern economics tends to chase whatever can be cleanly measured and to run lots of regressions, while neglecting reasoning that relies on intuition, introspection and imagination to think about things that can’t be measured, like human welfare. Consumer surplus gets neglected because it can’t be pinned down empirically; large parts of the demand curve that matter for the welfare impact of markets never show up in data. But ignoring consumer surplus just because it’s not practically quantifiable is the classic “looking for your keys under the streetlight” mistake: the easy-to-measure isn’t the same as the important, and human welfare is the thing we should really be looking for markets to promote. It’s no good to become indifferent to human welfare because it doesn’t show up in a dataset. Loose, intuitive arguments are the only way we can reason about certain things that matter a lot. So please read what follows with a readiness to take producer and consumer surplus seriously, without expecting exact numbers.

The Urbanization Effect: How Immigration Impacts the Market for Preexisting Housing

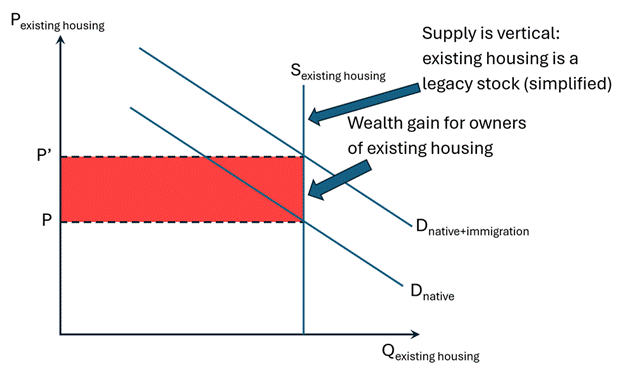

Now it’s time to present my truer models of immigration and housing, and the truer, more lucid welfare analysis that they enable. As stated above, the key segmentation to study here is existing versus new housing. A stylized representation of the market for existing housing is shown in Figure 4.

Crucially, in Figure 4, the supply curve is vertical. That’s because preexisting housing cannot, almost by definition, be built. There are nuances here, with restorations of old houses and whatnot, but essentially, this is a market for a good that is in fixed supply. And that keeps the welfare economics simple: as demand rises, the price rises, and the red region in Figure 4 is the welfare gain for incumbent homeowners.

Most of the literature cited by Nowrasteh in his article is directly relevant to this effect. The scholars he cites track the local impact of immigration increases, and find that house prices rise. That’s a wealth gain for local homeowners in those areas, but it’s not necessarily a welfare loss for homebuyers who would have moved in, because they have other options. And that brings us to the market for new housing.

The Low-Cost Labor Effect: An Immigration-Driven Building Spree

The key fact to keep in mind when considering the impact of immigration on new housing is that, nationwide, there’s a whole lot of cheap, undeveloped land. As a result, there are a lot of places where house prices are pretty close to the actual cost of erecting structures. If it costs $100,000 in materials and labor to build a house, the land required to build the house on is available for a tiny fraction of that in many places, and the house price in a competitive housing market will not be much above $100,000.

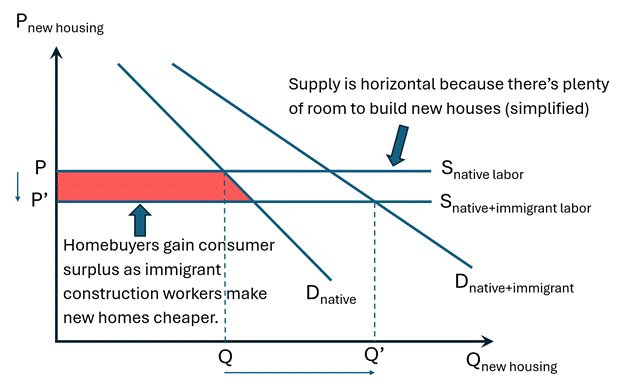

Construction, like most industries, requires a mix of skills to do its work, and some of those skills are relatively advanced. But in general, it requires less education and more sheer muscle and hard work than most industries. Naturally, therefore, it attracts a disproportionately immigrant workforce. Increased immigration could be done in different ways, but since the world population is, on average, somewhat younger and a lot less educated than that of the United States, it would demographically feed into construction jobs more than other sectors. Builders would face easier recruitment and would probably pay somewhat lower wages. Of course, demand for new housing would also increase since immigrants need places to live. Figure 5 shows the impact of that on supply and demand specifically for new housing:

In Figure 5, the supply curve for new housing is drawn as horizontal, because (again) there’s so much cheap land. You might argue that the supply curve should slope a little bit up, because there’s some scarcity of usable land, or on the other hand, a little bit down because of economies of scale in homebuilding, and part of the reason a horizontal supply curve is good is because it takes into account the way those factors offset. Immigration causes the supply curve to shift down: that’s the low-cost labor effect.

A subtle factor to bear in mind is that the density amenities enjoyed by new housing can be expected to stay roughly the same as immigration expands cities. New housing is often built on the margins or cities, while some new housing is infill, but there’s no particular reason to think immigration would affect the mix either way. Immigration would grow and densify cities, and new housing would tend to shift outward from urban cores. Urban cores would enjoy more of the amenities of density, the jobs and the shopping, compared to before, but for new housing, the degree of urbanization in the environment would be similar.

And that’s why I’ve taken the liberty of treating Dnative as still operative under increased immigration. Native buyers of new homes would have similar preferences on a spectrum of density versus price, and would buy houses further from urban cores than before, but with similar levels of density and its accompanying amenities. The difference is that the low-cost labor effect would make similar housing cheaper than before, so native homebuyers would buy “more house” and/or have more money to spare.

The Great Immigration Housing Windfall

Let’s translate this into human terms. Suppose a major liberalization of immigration took place, and the number of immigrants entering the country rose by a few million per year. How would this affect your housing? It depends on your situation.

If you’re a homeowner in a city, or a suburb of a major metro, or a medium-sized city or small town, you could expect to enjoy big gains in your paper net worth in the face of rising demand for housing like yours. Your neighborhood would get busier, and you’d see a lot of construction cranes rising as builders got busy and the city or town got more dense. There would be more jobs nearby, more shopping, more restaurants, more services– but also less peace and quiet. From there, you’d have some options.

You might like the new lifestyles that a busier place makes possible. You might like the new restaurants, the new shops, the professional opportunities, the churches, the bustle. In that case, you might benefit, not so much because of the rising dollar value of your real estate, as because of your preferences. You might also profit financially by your more urbanized location, renting a room through Airbnb or selling handicrafts over Craigslist or something. Your more valuable home could also be leveraged to borrow money, which you could use to continue your education, or to start a business. That might pole vault you into greater prosperity, or you might be less fortunate, but even if the education doesn’t pay off in a better job, or if the business fails, it’s nice that you only have to sell your home and move someplace cheaper, rather than declaring bankruptcy.

Now suppose instead that you were a renter when the immigration surge takes place. As housing prices rise, places that you might have lived become unaffordable to you. But if you go house shopping, builders staffed by a low-cost immigrant workforce have a lot to offer you in the new neighborhoods that are emerging, or in new infill developments. You’ll probably find that you have to move further out than you would have, in order to find housing that you can afford. But the growing city can still offer you the urban amenities there. A mix of natives shifting outwards and immigrants creates the critical mass of demand to support new stores and restaurants in places that were previously sleepy or wild. And the housing itself is cheaper per square foot.

An important nuance is that the low-cost labor effect impacts not only homebuilding but also maintenance. Maybe you own a big place in the countryside where land is abundant and cheap. It doesn’t help you that homebuilding is lower in cost. You’re in a rare situation where your net worth may actually fall, as structures like yours become easier to replace due to low-cost labor, and land values don’t rise enough to offset that. On the other hand, if you stay put, all those immigrant construction and repair workers make it easier to replace roofs, fix pipes, add out-buildings, and the rest of what it takes to keep a home livable or upgrade it over time.

Once you understand the macroeconomics of immigration and housing, to proliferate examples of the great immigration windfall is as easy as finding hay in a haystack. The big takeaway is shown in Figures 4 and 5. But how is it possible for the impact to be so comprehensively positive? Isn’t this all too good to be true? To this, there are two answers.

First, it’s unfortunate and harmful that billions of people are forced to live in places where they can’t be productive, and an enlightened immigration policy that allows people to move and flourish unlocks a huge rising tide of prosperity will naturally yield big gains for lots of people in lots of different ways. A richer world can enrich everyone, with the gains being allocated through competitive markets. It’s a case in point of the virtues of free markets, the larger pattern that things very often get better when government gets out of the way.

Second, revealed preference proves that people like to live near each other, and immigration allows more of that creative proximity to occur. Immigration enriches the division of labor, and supplies more of the productivity and pleasure that arise from complex patterns of specialization and trade, without depleting the options for more quiet, rural lifestyles for those who prefer them.

Most Americans are homeowners. Maybe if they understood the capital gains they are poised to enjoy if immigration is liberalized, public opinion would be more welcoming.

If immigration doesn't cause any increase in housing supply, then it will tend to raise housing prices and make housing less affordable. But is immigration really not raising housing supply in Spain? What's the evidence?

Some things that make the question tricky to answer:

1. Short run versus long run: it takes time for home building to mobilize and complete projects. Sometimes it just takes little patience.

2. What's the counterfactual? What would housing supply look like without immigration?

There's a theoretically robust scenario in which immigration doesn't trigger any new housing supply, because there's an overhang of excess housing that makes prices depressed. Immigration might cause house prices to rise, yet not enough to make the equilibrium price exceed the cost to build new homes.

Thanks Alex! I love that he posts a guest post that's explicitly critical of him, albeit in a friendly way. Commenters: I'll watch this space and provide feedback from the author to defend/explain. So please articulate your questions/doubt/pushback!